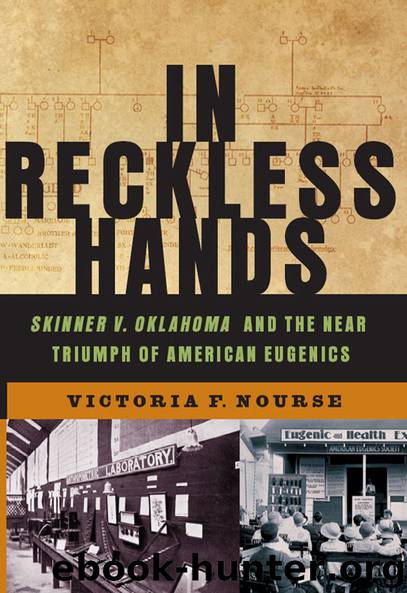

In Reckless Hands by Victoria F. Nourse

Author:Victoria F. Nourse

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2008-08-28T04:00:00+00:00

By the end of 1940, polls showed that a substantial number of Americans believed that Hitler’s Fascism would enslave all of Europe. Now, the embrace of things German carried risks. The ever zealous Human Betterment Foundation would aim to “steer clear” of the German eugenics they once embraced. Eugenics enthusiasts would begin to reframe their claims in the political rhetoric of the day. When Frederick Osborn, a nephew of the prominent eugenicist Henry Fairfield Osborn, wrote a book rejecting many of his uncle’s assumptions, Time magazine called it a “eugenics for democracy.” The book, Preface to Eugenics, was lauded as a “new, environmental eugenics.” Eugenicists were said to have finally given up their enchantment with heredity as predestination and taken a more moderate position (though this merely solidified a move already underway since the early 1930s, when the “social reasons” for eugenics had been touted—that is, the bad behavior of badly situated parents). Now, said Time, Osborn the younger had “presented the scientific evidence to demolish the last remnants of his uncle’s fancy.” There was no “menace” of the feebleminded, reported Osborn. The thin red line between the super-procreative feebleminded and the under-procreating gentry was really a good bit thicker than eugenicists had predicted; the birth rates of the mentally afflicted were, in fact, quite low.27

One might have thought that a “democratic eugenics” was impossible. The great eugenic popularizers—Albert Wiggam and Michael Guyer, Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard—had all railed against democracy, calling its egalitarian premises naïve, unscientific, unsound and weak, the “rule of the worst.” The Harvard geneticist Edward East dubbed equality a “cult” the Berkeley zoologist S. J. Holmes called democracy a “fetish.” The zoologist Michael Guyer wrote that equality was “beautiful” but “misleading” the popularizer Paul Popenoe went so far as to write that “democratization” of the country might be “dangerous.” Even in 1939, S. J. Holmes was prepared to insist that one of the great virtues of eugenics was that it was a science of “natural inequality.”28

Yet, in 1940, even eugenicists were bowing to the political forces of the day, trying to make eugenics consistent with American ideals of equality and democracy and individualism. Voluntary sterilization and birth control, Osborn urged, were the appropriate forms of eugenics in a democracy. This move to a “democratic eugenics” did little, however, to resolve the question of sterilization. Osborn was a eugenicist, even if a reformed one. He rejected the notion of wholesale, compulsory sterilization—but took the position that sterilization was appropriate for individual cases of the feebleminded. Organized eugenics may have wrapped itself in the rhetoric of democracy, but sterilization would not die.29

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Vaccine Court by Rohde Wayne(1187)

Inside the Criminal Mind by Stanton Samenow(999)

Lecretia's Choice by Matt Vickers(962)

Babies of Technology by Mary Ann Mason(922)

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism by Anne Case(857)

Five Last Acts by Chris Docker(854)

America's Bitter Pill: Money, Politics, Backroom Deals, and the Fight to Fix Our Broken Healthcare System by Steven Brill(850)

America's Bitter Pill by Steven Brill(805)

Memoir of a Race Traitor by Mab Segrest(664)

The Collected Tales by Nikolai Gogol(662)

Medical Law: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) by Charles Foster(660)

Mental Illness, Human Rights and the Law by Brendan D Kelly(653)

Introduction to Health Care Management by Sharon B. Buchbinder Nancy H. Shanks(650)

Genomic Messages: How the Evolving Science of Genetics Affects Our Health, Families, and Future by George Annas & Sherman Elias(629)

Genomic Messages by George Annas(606)

A New Leaf by Alyson Martin Nushin Rashidian(596)

Pediatric Forensic Evidence by David L. Robinson(595)

Marijuana Law in a Nutshell by Mark Osbeck & Howard Bromberg(589)

In Reckless Hands by Victoria F. Nourse(568)