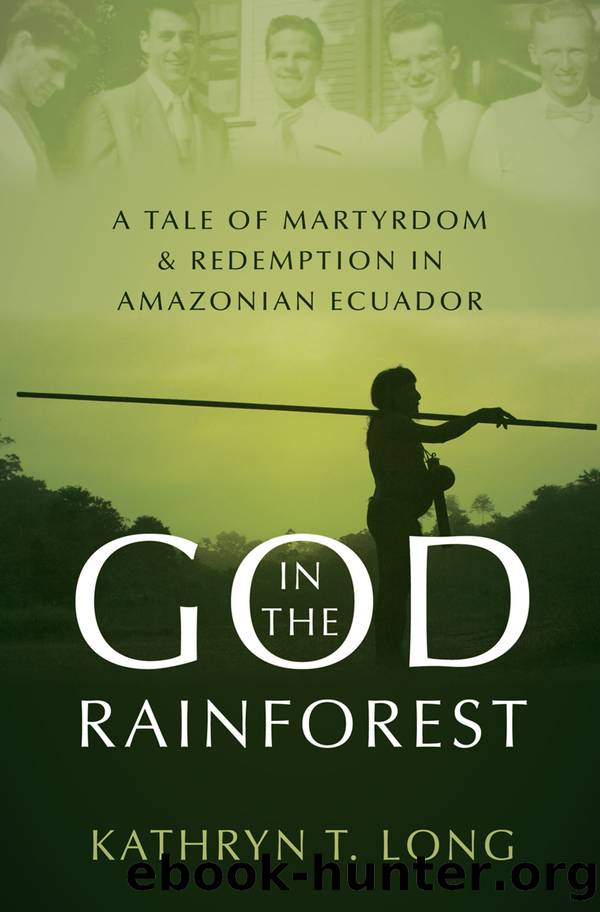

God in the Rainforest by Kathryn T. Long

Author:Kathryn T. Long

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2018-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

Indigenous Healthcare Promoters

The SIL team offered the Waorani opportunities for basic training as healthcare promoters (paramedics) and, to a lesser extent, dental hygienists. Jung already had done some individualized training, but growing demand highlighted the need for a more structured program. Between 1979 and 1980 nurses Lois Pederson and Verla Cooper from SILâs clinic at Limoncocha helped train fourteen Wao health promoters who represented seven communities within the protectorate.39 The training included ongoing mentoring and emphasized prevention as well as cure.

âWhen Ãnkæde arrived at Limoncocha to help me with translation, the first thing he demanded was boiled water to drink, and wanted to know where he should throw his garbage!â reported Peeke.40 Other Waorani learned to provide dental care, primarily how to encourage good dental hygiene and when and how to pull teethâand when not to. Because of the training required and the dangers of working with mercury, filling cavities and other more complicated procedures were left for periodic dental clinics staffed by outsiders.41 These efforts marked the beginning of ongoing healthcare training that eventually would be carried out by other agencies as the impact of outside contact on Wao health became ever more obvious.

Training indigenous paramedics and encouraging Waorani to use medicines more judiciously were official goals during the late 1970s. But SIL staff often were called on to respond to specific medical emergencies. That was Pat Kelleyâs experience in February 1978, when Wentæ, a Wao teenager about sixteen or seventeen, severed the femoral artery of his right leg in a spear fishing accident. His relatives carried him to the airstrip at Tzapino, the clearing where he lived. The next morning a small plane flew him, along with Kelley and Wentæâs aunt Dawa, to Limoncocha. SILâs DC-3 then arrived, having flown from Quito specifically to take Wentæ back to a hospital there.

Due to what might be considered miraculous circumstances (it was rare that unscheduled flights involving rainforests and Andes mountain passes could be coordinated so quickly), Wentæ was checked into the Vozandes mission hospital in Quito by 5:10 p.m. on the day after his accident. To save the teenagerâs leg, doctors did a graft to replace the six inches of artery that had been severed and damaged. The next two weeks were touch and go. Wentæ not only had survived the original accident and not bled to death, but with the help of the Vozandes staff and resident Ecuadorian doctors, he also lived through other brushes with death after the first operation. These included pulmonary edema, the rupture of the graft, the amputation of his leg, and a subsequent systemic infection as well as a localized infection on the stump of the amputated leg.

Dawa and Kelley spent days, and sometimes nights, at Wentæâs side. For Kelley, the experience meant trying to navigate a critical situation in twoâsometimes threeâvery different languages and cultures. âThe emotional load or price was heavier than anything else,â she later reflected. âThe initial incident, the decisions, the diagnosis, the possibilities or alternatives [including the issue of Wentæâs and Dawaâs giving informed consent for the amputation] .

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7494)

Why I Am Not A Calvinist by Dr. Peter S. Ruckman(4149)

The Rosicrucians by Christopher McIntosh(3513)

Wicca: a guide for the solitary practitioner by Scott Cunningham(3167)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3132)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(3016)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2944)

To Light a Sacred Flame by Silver RavenWolf(2814)

The End of Faith by Sam Harris(2733)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2528)

Waking Up by Sam Harris(2454)

Nine Parts of Desire by Geraldine Brooks(2361)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2352)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(2326)

The God delusion by Richard Dawkins(2305)

Heavens on Earth by Michael Shermer(2278)

Kundalini by Gopi Krishna(2180)

Chosen by God by R. C. Sproul(2161)

The Nature of Consciousness by Rupert Spira(2104)