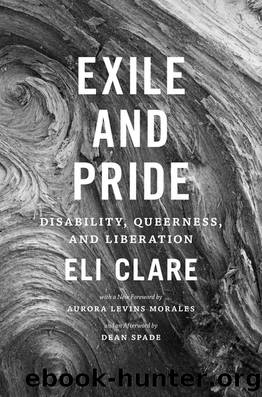

Exile and Pride by Eli Clare

Author:Eli Clare [Clare, Eli]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Duke University Press

Published: 2015-08-07T00:00:00+00:00

During the freak showâs heyday, todayâs dominant model of disabilityâthe medical modelâdid not yet exist. This model defines disability as a personal problem, curable and/or treatable by the medical establishment, which in turn has led to the wholesale medicalization of disabled people. As theorist Michael Oliver puts it:

Doctors are centrally involved in the lives of disabled people from the determination of whether a foetus is handicapped or not through to the deaths of old people from a variety of disabling conditions. Some of these involvements are, of course, entirely appropriate, as in the diagnosis of impairment, the stabilisation of medical condition after trauma, the treatment of illness occurring independent of disability, and the provision of physical rehabilitation. But doctors are also involved in assessing driving ability, prescribing wheelchairs, determining the allocation of financial benefits, selecting educational provision and measuring work capabilities and potential; in none of these cases is it immediately obvious that medical training and qualifications make doctors the most appropriate persons to be so involved.15

In the centuries before medicalization, before the 1930s and â40s when disability became a pathology and the exclusive domain of doctors and hospitals, the Christian western world had encoded disability with many different meanings. Disabled people had sinned. We lacked moral strength. We were the spawn of the devil or the product of godâs will. Our bodies/minds reflected events that happened during our mothersâ pregnancies.

At the time of the freak show, disabled people were, in the minds of nondisabled people, extraordinary creatures, not entirely human, about whom everyoneââprofessionalâ people and the general public alikeâwas curious. Doctors routinely robbed the graves of âgiantsâ in order to measure their skeletons and place them in museums. Scientists described disabled people in terms like âfemale, belonging to the monocephalic, ileadelphic class of monsters by fusion,â16 language that came from the âscienceâ of teratology, the centuries-old study of monsters. Anthropologists studied disabled people with an eye toward evolutionary theory. Rubes paid good money to gawk.

Hiram, did you ever stop mid-performance, stop up there on your dime museum platform and stare back, turning your mild and direct gaze back on the rubes, gawking at the gawkers, entertained by your own audience?

At the same time, there were signs of the move toward medicalization. Many people who worked as freaks were examined by doctors. Often handbills included the testimony of a doctor who verified the âauthenticityâ of the âfreakâ and sometimes explained the causes of his or her âfreakishness.â Tellingly doctors performed this role, rather than anthropologists, priests, or philosophers. But for the century in which the freak show flourished, disability was not yet inextricably linked to pathology, and without pathology, pity and tragedy did not shadow disability to the same extent they do today.

Consequently, the freak show fed upon neither of these, relying instead on voyeurism. The âarmless wonderâ played the fiddle on stage; the âgiantâ lived as royalty; the âsavageâ roared and screamed. These performances didnât create freaks as pitiful or tragic but as curious, odd, surprising, horrifying, wondrous. Freaks were not supercrips.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Blood and Oil by Bradley Hope(1558)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1419)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1389)

Daniel Holmes: A Memoir From Malta's Prison: From a cage, on a rock, in a puddle... by Daniel Holmes(1333)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(1315)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1296)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1167)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(1161)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(1146)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1132)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(1126)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(1117)

Cleopatra by Alberto Angela(1094)

A Woman by Sibilla Aleramo(1092)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(1075)

John (Penguin Monarchs) by Nicholas Vincent(1068)

Reading for Life by Philip Davis(1024)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(1024)

The Life of William Faulkner by Carl Rollyson(983)