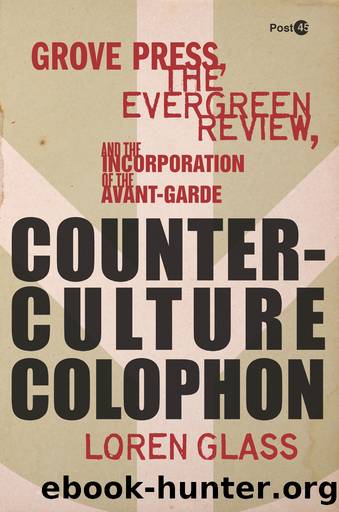

Counterculture Colophon: Grove Press, the <I>Evergreen Review<I>, and the Incorporation of the Avant-Garde by Loren Glass

Author:Loren Glass

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2013-09-14T16:00:00+00:00

Figure 26. Facsimile of Sade’s script on the endpapers of The Marquis de Sade: The Complete Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writings (1965).

In the postwar era, these questions tended to involve the metaphysical and historical extensions of the problem of evil. The publisher’s preface, which follows the translator’s foreword, confirms, “Now, twenty years after the end of the world’s worst holocaust, after the burial of that master of applied evil, Adolph Hitler, we believe there is added reason to disinter Sade.”102 Wilson in his New Yorker piece had already noted that “the atrocities [Sade] loves to describe do not today seem as outrageous as they did at first,”103 and Albert Fowler affirms that “it would be difficult to conjure up a holocaust more to the Marquis’s liking than the bombing of Hiroshima or a threat more suited to his imagination than that of the hydrogen bomb.”104 Using the vocabulary elaborated by John Peters in Courting the Abyss, one can understand the postwar Sade as an “abyss-artist” whose entire philosophic and aesthetic program is based in moral negation, and Seaver and Wainhouse as “abyss-redeemers” who “recognize the peril of the fiery deluge but believe that (vicariously) fathoming hell’s lessons justifies the risk of the descent and trust that enlightenment will follow their forays.”105 The constant coupling of liberty and evil in the proliferating metadiscourse about Sade in the 1960s situates Grove’s publication of his work within the larger framework of the postwar crisis of liberalism, whose adherents had been forced by the Holocaust and the atomic bomb to face the nihilism that had always shadowed its individualist ethos and that was currently squandering what remained of its moral capital in the jungles of Vietnam.

Seaver succeeded in getting Sade’s anniversary noticed in the terms he intended. One month after Seaver’s article was published, Alex Szogyi reviewed the first volume of Grove’s edition in the New York Times and opened with this paragraph: “One hundred and fifty years after his death in 1814, it is perhaps ample time for the Marquis de Sade to be welcomed into the public domain. For a world conscious of its own absurdity and the imminence of its possible destruction, the intransigent imaginings of the Marquis de Sade may perhaps be more salutary than shocking.” Szogyi goes on to praise Grove’s “generous, handsome, critical edition, beautifully printed with two major essays on the Marquis’s work.” He then concludes with the question, “May we not see his work as an immense plea for tolerance in a false and antiquated society?”106 This oddly unselfconscious juxtaposition of an absolute evil analogous to Hitler or the atom bomb and an absolute liberty dedicated to the tolerance of any and all deviance and desire epitomizes the contradictory image of Sade that Grove propagated. Sade was simultaneously a symbol of the evil of which humanity had recently proven itself capable and the freedom toward which it purportedly aspired. Seaver perceived this paradox more acutely than Szogyi and significantly thought it could be resolved only through making the work widely available.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

What's Done in Darkness by Kayla Perrin(25500)

Shot Through the Heart: DI Grace Fisher 2 by Isabelle Grey(18219)

Shot Through the Heart by Mercy Celeste(18160)

The Fifty Shades Trilogy & Grey by E L James(17774)

The 3rd Cycle of the Betrayed Series Collection: Extremely Controversial Historical Thrillers (Betrayed Series Boxed set) by McCray Carolyn(13189)

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson(12912)

Scorched Earth by Nick Kyme(11831)

Stepbrother Stories 2 - 21 Taboo Story Collection (Brother Sister Stepbrother Stepsister Taboo Pseudo Incest Family Virgin Creampie Pregnant Forced Pregnancy Breeding) by Roxi Harding(11040)

Drei Generationen auf dem Jakobsweg by Stein Pia(10216)

Suna by Ziefle Pia(10185)

Scythe by Neal Shusterman(9259)

International Relations from the Global South; Worlds of Difference; First Edition by Arlene B. Tickner & Karen Smith(8608)

Successful Proposal Strategies for Small Businesses: Using Knowledge Management ot Win Govenment, Private Sector, and International Contracts 3rd Edition by Robert Frey(8419)

This is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay(7695)

Dirty Filthy Fix: A Fixed Trilogy Novella by Laurelin Paige(6453)

He Loves Me...KNOT by RC Boldt(5804)

How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired by Dany LaFerrière(5378)

Interdimensional Brothel by F4U(5304)

Thankful For Her by Alexa Riley(5161)