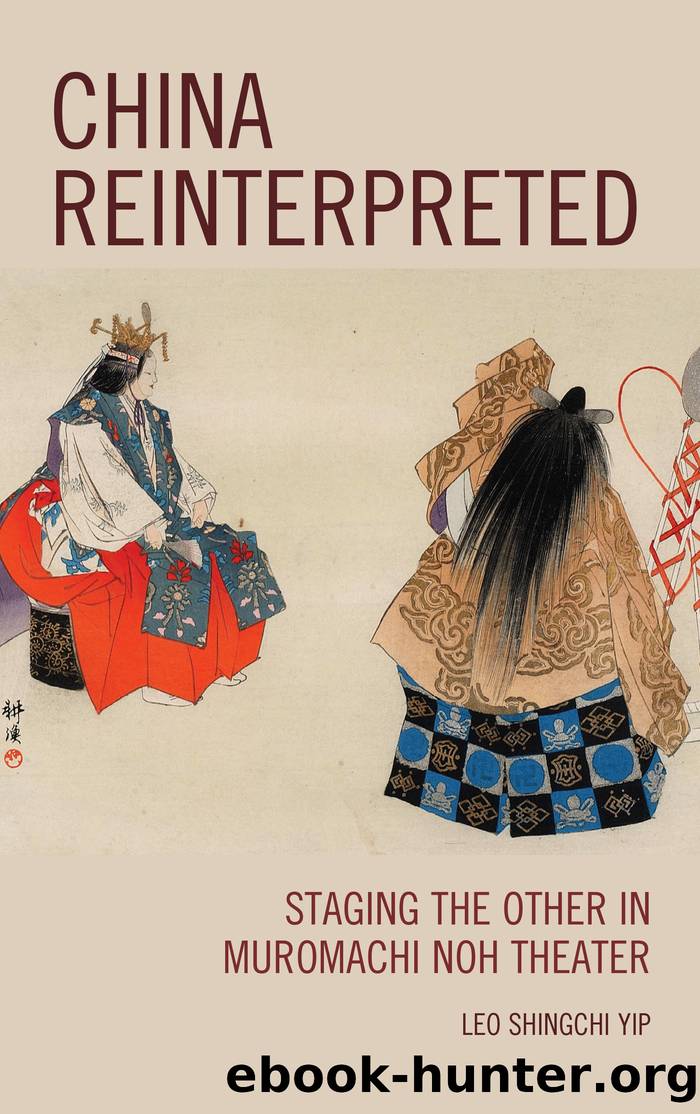

China Reinterpreted by Shingchi Yip Leo;

Author:Shingchi Yip, Leo;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: undefined

Publisher: Lexington Books

Published: 2012-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

The Sympathized Other and the Distanced Self

The stories of Wang Zhaojun and Yang Guifei have ample earlier renditions written by well-known Japanese literati, therefore ShÅkun and YÅkihi conjure up various traditional referenences to the Muromachi audience. In China, authors were inevitably held up to the sociopolitical analysis of their interpretations of Wang Zhaojunâs and Yang Guifeiâs stories and therefore might have been more inclined to justify the meaning of their interpretations. In Japan, authors were of course not susceptible to the same constraints, though they were likely responsive to the Japanese reception of their interpretations. The playwrights of ShÅkun and YÅkihi retold the Chinese stories in the light of Muromachi Japanese social, cultural, and political ideologies that underscore different aspects in contrast to the various interpretations in earlier Chinese renditions. Both plays depoliticized the Chinese stories to suit domestic tastes. Unlike the Chinese, who focused on the moral of the stories by scrutinizing the misbehavior of various human figures and charged the stories with didactic intent, the two plays are more concerned with constructing the Chinese characters as someone the Japanese audience would sympathize with. ShÅkun disregards the political implications such as the misrepresenting portrait that exposes the corrupt system of the Chinese court, the virtuous image of Wang Zhaojun who sacrifices herself for her country, and her struggle with the barbarian custom of remarriage to her stepson. YÅkihi, similarly, avoids the condemnation of the emperorâs infatuation over Yang Guifei that led to his neglect of state affairs, her quality as a femme fatale that brought the demise of the country, and her relativesâ gaining and abusing political power that ignited the An Lushan Rebellion.

By undermining the political implications and moral teachings, the playwrights Konparu Gon no Kami and Zenchiku were able to allocate depiction of the universal sentiment that the domestic audience might find it easier to identify with. It is evident that both playwrights were more interested in empathizing and appeasing the Chinese characters. In ShÅkun, the spirit of Wang Zhaojun appears in the mirror to communicate with her parents, whereas in YÅkihi, the shite Yang Guifei reveals her love attachment and sorrow. Such depictions allow the audience to sympathize with the Chinese characters, and somehow construct their own interpretations. Gon no Kami and Zenchiku made such participation possible by exploring the rationales for the charactersâ misfortune as the manifestation of the Buddhist idea of the impermanence of all things, especially the unavoidable parting that all living things must confront. Such interpretations of the Chinese stories should have engaged the medieval Japanese audience, not only because the Buddhist teachings of impermanence had been ingrained for centuries in Japanese culture, but also because they are in accordance with earlier Japanese perceptions of the Chinese stories.

Indeed, both playwrights encouraged the audience to embrace the Chinese Other by imbuing their plays with well-known Japanese literary works. Arguably the two Chinese plays with the richest Japanese literary precedents, ShÅkun and YÅkihi clearly demonstrate how earlier Japanese interpretations are utilized in the retelling

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(1058)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(979)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(976)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(976)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(900)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(809)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(784)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(775)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(771)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(733)

World Philology by(712)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(711)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(708)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(707)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(699)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(687)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(686)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(649)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(647)