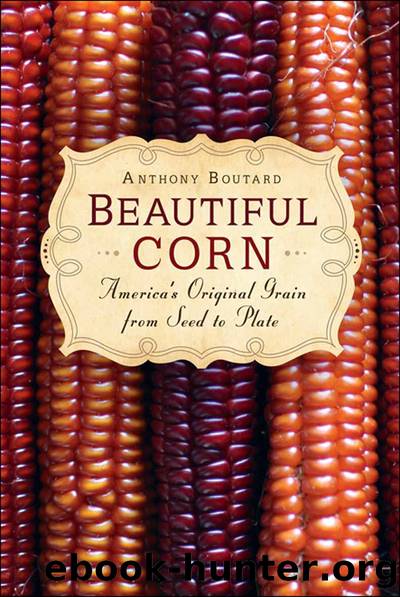

Beautiful Corn by Anthony Boutard

Author:Anthony Boutard [Boutard, Anthony]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781550925227

Publisher: New Society Publishers

Germination

It is late spring. The ground is prepared and corn kernels have been planted an inch or two (2.5 to 5 cm) within the earth. The first stage of growth takes place in the dark, damp soil, out of sight. Your first observation of the growing corn plant is best aided by a trowel.

As soon as a corn kernel finds itself in a warm and moist place, water absorbed by the aleurone and embryo breaks its dormancy and germination begins. Soil is not necessary. Corn will happily germinate in a wet seed package dropped on the way back from the garden, or wrapped up in a moist paper towel. Moisture alone is not enough; warmth is as essential to triggering germination as water.

Each type of corn seed has its own definition of warm: the flint varieties will germinate at around 50°F (10°C), dents need 60°F (16°C), and sweet corn needs at least 65°F (18°C). At Ayers Creek, mice cache the kernels from culled flint and popcorn ears left in the field during the autumn. Those kernels, stashed in their underground burrows, stay dormant through our wet winters and donât germinate until the following June, when the surrounding soil reaches the critical warmth.

Dormancy broken, the small plant resumes the growth suspended when the kernel reached maturity and the black line formed. The seedâs first functioning leaf, the scutellum, releases the plant hormone gibberellic acid, a signal to the aleurone to start producing enzymes. These enzymes move out of the aleurone and into the starchy endosperm, initiating disassembly of the long starch molecules into simple sugars and reversing the assembly process that packed up the kernel for storage. Other enzymes break down the proteins and fats into transportable units. The scutellum absorbs and directs the nutrition and energy that was stored in the endosperm the previous year to the growing parts of the new plant. That is the scutellumâs sole function and it will never grow beyond the kernel. At this point everything the plant needs to grow, except water, is provided within the kernel. Nonetheless, the plant has a limited supply of stored food, so time is of the essence in this early stage of growth.

The first order of business for the seed is to access a steady supply of water by growing a root. Even towering trees break their dormancy in the spring by producing a fresh growth of roots underground before the leaves appear. Three to six days after planting, a rupture appears on the embryo side of the kernel and the coleorhiza, from the Latin for âroot sheath,â emerges. Unique to the grasses, the coleorhiza has only one function; after tearing open the tough pericarp, its job is done, and the coleorhiza stops growing. Inside the coleorhiza is the radicle, or primary root. The root pushes out of its sheath into the surrounding soil. As it grows, delicate hair-like structures emerge. Called root hairs, they are the part of the root that absorbs the water and minerals from the surrounding soil.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(6693)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4198)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3569)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3292)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(2950)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(2932)

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(2556)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2360)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2299)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2291)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2270)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2215)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2070)

Will by Will Smith(2042)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2012)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(1973)

The Chimp Paradox by Peters Dr Steve(1862)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (25th Anniversary Edition) by Covey Stephen R(1836)