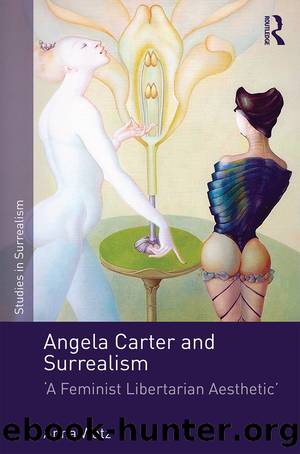

Angela Carter and Surrealism by Watz Anna;

Author:Watz, Anna;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Taylor and Francis

Notes

1As Gamble argues elsewhere, â[t]âo a certain extent, Carterâs fascination with pornography can be traced to her experiences in Japan, a country in which, as she portrayed it, the sadomasochistic fethishisation of the female body is commonplaceâ (1997, 98).

2Suleiman reaches this conclusion without much actual reference to surrealism. Instead, her reading concentrates primarily on Carterâs postmodernist narrative strategies and her allegiance with the cultural pessimism of Herbert Marcuse and Guy Debord, in whose writings âthe technological appropriationâ of surrealism and liberation philosophy is shown to have been exploited for capitalist aims. David Punter (1985) and Gamble (2006a) also explore the links between Doctor Hoffman and the thought of Marcuse.

3E.g. âI DESIRE THEREFORE I EXISTâ; (DH, 211); âBE AMOROUS! ⦠BE MYSTERIOUS! ⦠DONâT THINK, LOOKâ (26; capitals in the original); âGo in fear of abstractions!â (35); âMy passions, concentrated on a single point, resemble the rays of a sun assembled by a magnifying glass; they immediately set fire to whatever object they find in their wayâ (97); âI have become discontinuousâ (147).

4Parodic allusion was indeed a frequent surrealist practice, which Carter employs to her own critical ends, in a process in which the surrealists themselves end up as one of the targets of her parody. Carter is thus indebted to surrealism in her parodic analysis of archetypal representations of gender and desire, even as she critiques surrealism for its complicity in perpetuating them.

5Of course, the echo of the German Gothic writer E.T.A. Hoffmann in the Doctorâs name is not accidental. In âThe Hoffmann Connection: Demystification in Angela Carterâs The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr. Hoffmanâ, Peter Christensen elucidates the links between Carterâs novel and Hoffmannâs story âNutcracker and Mouse-Kingâ (1994). For further discussion of the link between Doctor Hoffman and E.T.A. Hoffmann, see Suleiman ([1994] 2001, 104).

6The name Desiderio â âthe desired oneâ â might refer to the pseudonym Monsu Desiderio, used by three different artists during the Baroque period: François de Nomé and Didier Barra, both born around 1593, and a third artist sometimes identified as Francesco Desideri (Caws 1997, 169). The most famous of these â Nomé â was considered by the surrealists as one of their artistic forerunners (Vaneigem [1977] 1999, 56).

7Benjamin Péret was one of the poets in the circle around Breton.

8In an interesting analysis, Maggie Tonkin investigates the connection between Albertina and the muse-like Albertine in Marcel Proustâs à la recherche du temps perdu (1913â27) (2002). For an additional analysis of the Proustian elements in Doctor Hoffman, see Natsumi Ikoma (2008).

9According to critics such as Gauthier and Hal Foster, this idealised love is essentially regressive, strongly resembling a desire for the return to a pre-Oedipal symbiosis with the mother. Gauthier writes: â[t]âhis connection with the other â a connection of fusion and effusion â is a regressive relationship, the type of connection that exists between a child and its mother. This is a key point to the understanding of surrealismâ (1971, 77; n.d., 30). Some of the imagery that Desiderio â who has never known his own mother â encounters in the peep-show is evocative of such maternal plenitude.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(1049)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(979)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(976)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(968)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(890)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(805)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(773)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(773)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(770)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(731)

World Philology by(711)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(710)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(707)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(705)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(697)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(685)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(675)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(648)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(644)