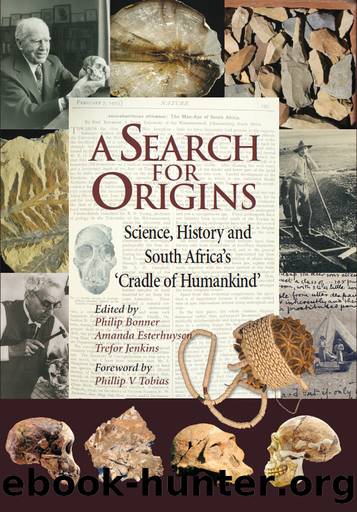

A Search for Origins by unknow

Author:unknow

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781776142309

Publisher: Wits University Press

Published: 2007-03-15T04:00:00+00:00

Figs. 9.5a & b Plan and section drawings of typical storage pits at Broederstroom, and photograph of a storage pit at the site

Broederstroom, like many Early Iron Age sites, also incorporated other storage facilities. In addition to raised grain bins, grain may also be stored in underground pits which are smeared with dung and then sealed with a stone. Methane gas from the dung lining kills insects and helps to preserve the produce. If kept dry, the produce is edible for several years and serves as an insurance policy against bad times. After their initial use, these storage pits become rubbish dumps and are of tremendous value to Iron Age research.

The excavations at Broederstroom yielded several such storage pits (Mason 1981; Huffman 1993). A metre-deep pit with a dung lining lay underneath hut Kc, and more were found in Area Azc-Azd (Fig. 9.1). Pit Azzr, for example, was some 2.5 metres below the present surface level, and it contained at least three dung smears (Figs. 9.5a and 9.5b), indicating that it had been used to store grain, then emptied, re-smeared and used again at least twice. As with other pits at Broederstroom and elsewhere, it became a rubbish dump.

These storage pits are important to the migration-versus-diffusion debate. Significantly, the pit fills often contain characteristic pottery together with pole-and-daga fragments, broken grindstones, metal slag and the broken bones of domestic cattle, sheep and goats. Because these items consistently occur together, they show that the Iron Age way of life came to southern Africa as a material-culture package.

Broederstroom and the antiquity of lobola

Another debate involving Broederstroom concerns the nature of early mixed-farming society and the antiquity of lobola â the preference for bridewealth in cattle. In recent times this preference has been a defining characteristic of Eastern Bantu speakers in southern Africa. Among other things, the exchange of cattle for wives underpinned kinship relations and political power. Because of this central role, the antiquity of lobola is an important topic.

Broadly speaking, there have been two schools of thought. In the first, lobola was thought to have evolved in southern Africa a few centuries after mixed farmers entered the region. To some Africanists, the mode of production of Early Iron Age societies shared more similarities than differences with Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers, until a natural increase in cattle herds in the eastern lowveld led to the development of new social relations and lobola (Hall 1986). Before the ninth and tenth centuries, according to this view, cattle were probably not important because the lowveld environment was initially unsuitable. Cattle herds could only increase once coastal forests that sheltered tsetse fly had been cleared by slash-and-burn cultivation. As cattle herds increased over time, cultural attitudes towards them, it was thought, shifted from communal to private ownership.

This first school of thought was based on locational data and faunal remains. For example, early settlement locations throughout East and southern Africa show a preference for broken country with access to water and cultivatable soils: pasturage was not the primary factor.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4287)

Never by Ken Follett(3924)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3838)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3367)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3361)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3057)

Will by Will Smith(2894)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2345)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2321)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2316)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2295)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2214)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2210)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2185)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2181)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2108)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2083)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2050)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1998)