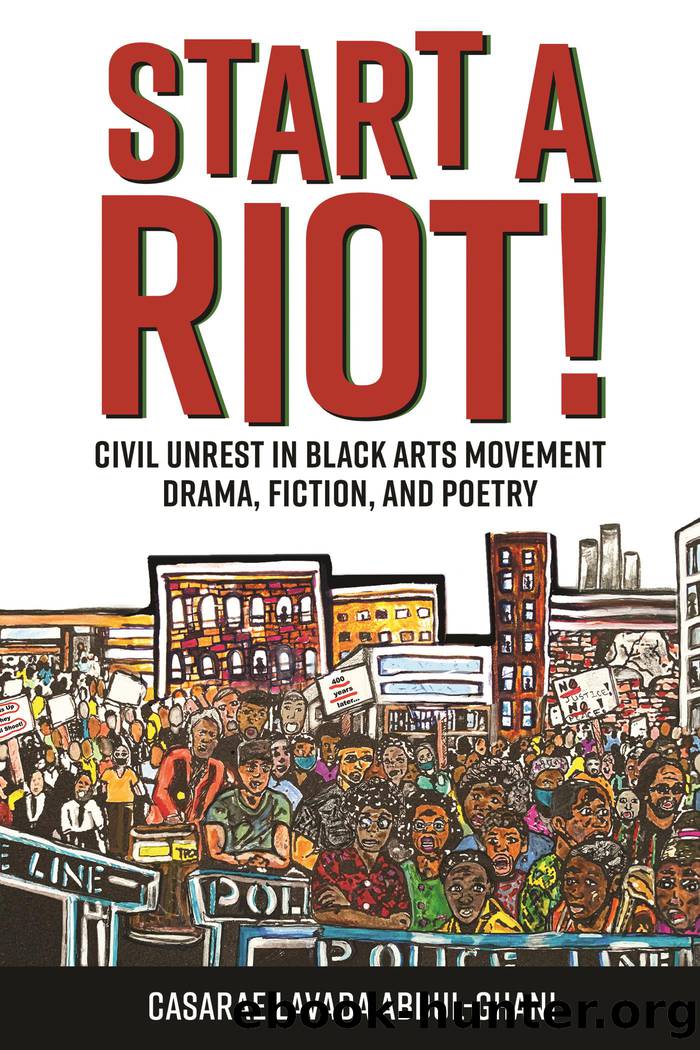

Start a Riot! by Casarae Lavada Abdul-Ghani

Author:Casarae Lavada Abdul-Ghani

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University Press of Mississippi

Published: 2022-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

THE HISTORY OF HARLEM AND ITS REPRESENTATION IN BRONX

Harlem, the setting of Bronx, has a complicated Black history. Between the 1880s and early 1900s, white landlords who desperately wanted to keep the neighborhood exclusively white collectively formed racially restrictive covenant laws. Such a plan on the part of white Harlemites would maintain their real estate property at a high value and attract other owners interested in purchasing the property. In âHarlem: The Making of a Ghetto,â Gilbert Osofsky notes that Blacks were historically considered the âmost depressed and traditionally worst-housed peopleâ (Osofsky 20). In other words, Black Harlemites were seen more as a liability than an asset in terms of wealth building. Why were they seen as a liability? What did they do to drive down property values? This prejudice stemmed from the historical nature of African descendants in the United States. For Black people, regardless of their national affiliationâwhether they migrated north to New York or immigrated from the Caribbean or South Americaâracism limited their opporÂtunities to own property or work in sectors where they could earn higher wages. Redlining and other methods for restricting Blacks to particular areas in Harlem became so pronounced that, as Osofsky points out, some covenant agreements âeven put a limitation on the number of Negro janitors, bellboys, laundresses, and servants that could be employed in a homeâ (21). Such organizations as the Harlem Property Ownersâ Improvement Corporation and the West Side Improvement Association were adamant about dismantling âthe Negroâs steady effort to invade Harlem,â as many whites perceived it (21). In some sections of Harlem, landlords placed whites-only signs in their apartment buildings. A movement had begun to keep the growing population of Blacks, particularly in Upper Manhattan, at low or relatively nonexistent levels. As Osofsky notes, âNegro realtors were contacted and told they would be wasting their time trying to find houses on certain streetsâ (22). By 1917 the New York state government confirmed that âracially restrictive housing covenants were unconstitutionalâ in Harlem, and Black people were afforded the opportunity to purchase, rent, and sell the property to other Black tenants (22). Although Black Americans could access a plethora of housing in Harlem, they were still conscious of racial violence happening throughout America.

On July 28, 1917, W. E. B. Du Bois, who was living in Harlem at the time, organized a silent march of Black children, women, and men down New Yorkâs Fifth Avenue to protest lynching and anti-black violence exhibited in East St. Louis. Soyica Diggs Colbert argues that this kind of protest signaled âan act of enfranchisement that called attention to black citizensâ disenfranchisementâ (Colbert, Black Movements 144). In many ways, the protest coalesced the mass demonstration for Black Harlem residents to equally protest against other forms of disenfranchisement, including housing segregation that continued in Harlem amidst unconstitutional housing laws.10 Through the subtle removal of racially restrictive covenants in Harlem, a prominent Black middle class grew and made Harlem an artistic and ethnically vibrant community, home to a New Negro/Harlem Renaissance.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(1049)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(977)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(973)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(968)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(890)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(805)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(773)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(773)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(770)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(730)

World Philology by(711)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(710)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(706)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(705)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(697)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(685)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(674)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(648)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(644)