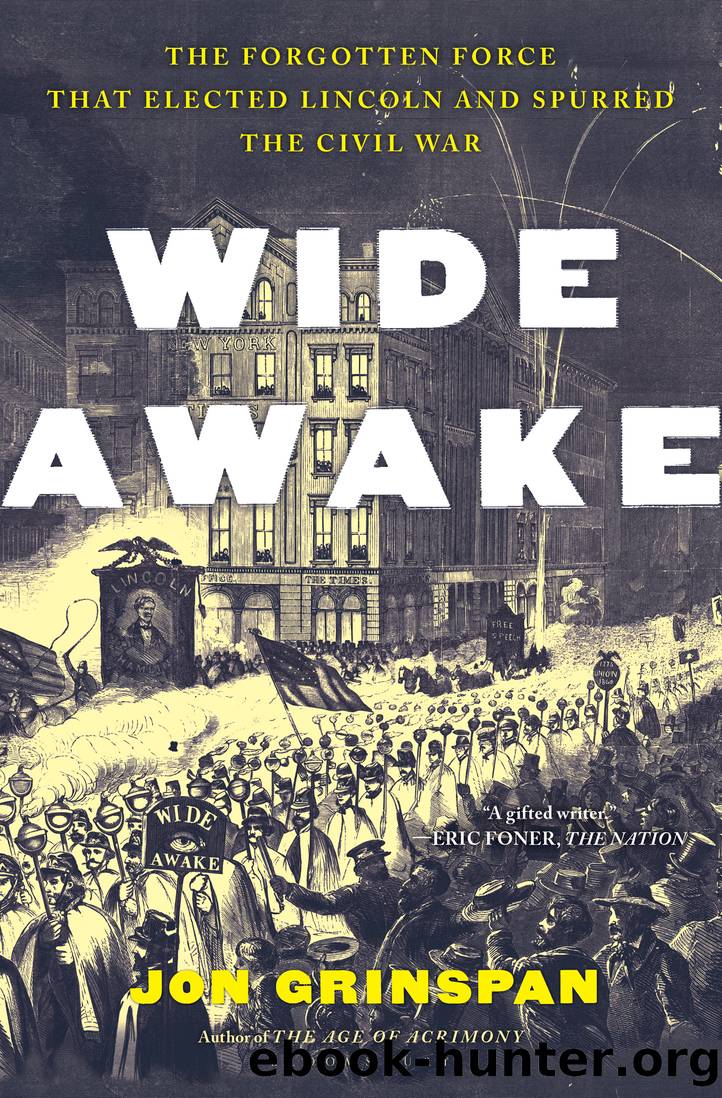

Wide Awake by Jon Grinspan

Author:Jon Grinspan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

PART THREE

The Transmogrification of the Wide Awakes

CHAPTER TEN

Permit Me to Suggest a Plan

Some dapper goon had Frederick Douglass by the hair. Another tried to wrench a wooden chair from his hands. Sleeves rolled up, powerful forearms tensing, Douglass grappled manfully for the chairâs wooden spindles. Fellow abolitionists dove in on his side, the ferocious Lewis Hayden likely among them. Hoarse voices in the audience were yelling in Douglassâs direction: âPut him out! Down him! Put a rope round his neck!â1

At Wheeling, rowdies had surrounded the theater. In Baltimore they had swarmed the aisles, but Wide Awakes kept them off the stage. In Boston, weeks after the election that was supposed to have settled everything, there were no Wide Awakes in sight. Lewis Hayden had gathered the American Anti-Slavery Society to mark the one-year anniversary of John Brownâs execution and consider âthe Great Question of the Age, âHow Can American Slavery Be Abolished?â â But infuriated by the growing national crisis, proslavery âunionistsâ stormed the hall and seized the stage, proposing to save the nation by mobbing down abolition.2

The thugs in Boston were an unusual lot, a noticeably well-dressed crew of Beacon Street aristocrats, Harvard students, and conservative Constitutional Unionists. Their leader, a loudmouthed wool manufacturer named Richard S. Fay, had fifty thousand dollars to his name and a working knowledge of committee rules. Even as his buddies pulled hair, Fay commandeered the podium and introduced a series of antiabolitionist resolutions. âResolved: That the people of this city have submitted too long in allowing irresponsible persons and political demagogues to hold public meetings,â Fay snarled. âThey have become a nuisance, which, in self-defense, we are determined shall hence forward be summarily abated.â When some abolitionists in the crowd made a good-faith effort to reason with the invaders, arguing that surely âevery man is entitled to express his own opinion,â mobs hooted, âNo! No!â3

Frederick Douglass was more blunt. One of Americaâs most experienced speakers, used to being heckled and Jim Crowed, he was nonetheless surprised by the vehemence of this mob. He could only lob sentence fragments over the chaos of Boston accents arguing over whether he should be silenced: âThis is one of the most impudent, (order! order!) barefaced, (knock him down! sit down!) outrageous attacks on free speech (stop him! you shall hear him!)âI can make myself heardâ(great confusion) that I have ever witnessed in Boston or elsewhere.â But Douglas understood who had sent these noisy goons. âI know your mastersââhe pointed a shaking finger at the riotersââI have served the same master that you are serving. You are serving the slaveholders.â4

After three hours of warring speeches, scrums for the podium, and wrestling over chairs, the police forced everyone out, including the abolitionists who had booked the hall for a private event. As the âunionistsâ left, they could be heard calling, âThree cheers for South Carolina!â5

Catching word of the unfolding mayhem, the German revolutionary refugee Karl Henzein rushed to the scene. He was too late. The Tremont Temple was dark, its massive front doors padlocked, Bostonâs streets deserted.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3368)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(3121)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2883)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(2361)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(2206)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2183)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(2143)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(2125)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(2095)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(2088)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1979)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1915)

Being George Washington by Beck Glenn(1880)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1787)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1683)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1679)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1665)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1655)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1636)