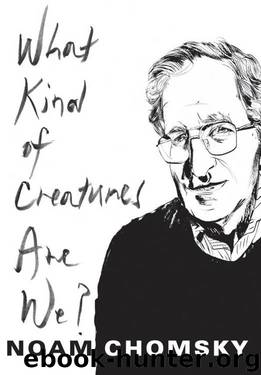

What Kind of Creatures Are We? (Columbia Themes in Philosophy) by Noam Chomsky

Author:Noam Chomsky [Chomsky, Noam]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Tags: PHI038000, Language Arts And Disciplines/Linguistics, Philosophy/Language, LAN009000

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2015-12-07T19:00:00+00:00

4 | THE MYSTERIES OF NATURE: HOW DEEPLY HIDDEN?

THE TITLE FOR this chapter is drawn from Hume’s observations about the man he called “the greatest and rarest genius that ever arose for the ornament and instruction of the species,” Isaac Newton. In Hume’s judgment, Newton’s greatest achievement was that while he “seemed to draw the veil from some of the mysteries of nature, he shewed at the same time the imperfections of the mechanical philosophy; and thereby restored [Nature’s] ultimate secrets to that obscurity, in which they ever did and ever will remain.” On different grounds, others reached similar conclusions. Locke, for example, had observed that motion has effects “which we can in no way conceive motion able to produce”—as Newton had in fact demonstrated shortly before. Since we remain in “incurable ignorance of what we desire to know” about matter and its effects, Locke concluded, no “science of bodies [is] within our reach,” and we can only appeal to “the arbitrary determination of that All-wise Agent who has made them to be, and to operate as they do, in a way wholly above our weak understandings to conceive.”1

I think it is worth attending to such conclusions, the reasons for them, their aftermath, and what that history suggests about current concerns and inquiries in philosophy of mind.

The mechanical philosophy that Newton undermined is based on our commonsense understanding of the nature and interactions of objects, in large part genetically determined and, it appears, reflexively yielding such perceived properties as persistence of objects through time and space, and as a corollary their cohesion and continuity;2 and causality through contact, a fundamental feature of intuitive physics, “body, as far as we can conceive, being able only to strike and affect body, and motion, according to the utmost reach of our ideas, being able to produce nothing but motion,” as Locke plausibly characterized commonsense understanding of the world—the limits of our “ideas,” in his sense. The theoretical counterpart was the materialist conception of the world that animated the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, the conception of the world as a machine, simply a far grander version of the automata that stimulated the imagination of thinkers of the time much in the way programmed computers do today: the remarkable clocks, the artifacts constructed by master artisans like Jacques de Vaucanson that imitated animal behavior and internal functions like digestion, the hydraulically activated machines that played instruments and pronounced words when triggered by visitors walking through the royal gardens. The mechanical philosophy aimed to dispense with forms flitting through the air, sympathies and antipathies, and other occult ideas, and to keep to what is firmly grounded in commonsense understanding and intelligible to it. As is well known, Descartes claimed to have explained the phenomena of the material world in mechanistic terms while also demonstrating that the mechanical philosophy is not all-encompassing, not reaching to the domain of mind—again pretty much in accord with the commonsense dualistic interpretation of oneself and the world around us.

I. Bernard Cohen observes

Download

What Kind of Creatures Are We? (Columbia Themes in Philosophy) by Noam Chomsky.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7354)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7137)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6800)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6621)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5791)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5519)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5196)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4456)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4314)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4279)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4264)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4257)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4133)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4012)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3969)