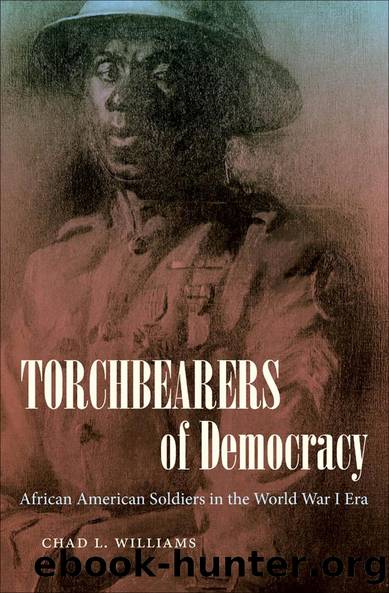

Torchbearers of Democracy by Chad L. Williams

Author:Chad L. Williams [Williams, Chad L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Ethnic Studies, African American Studies, History, Military, World War I, United States, 20th Century

ISBN: 9780807833940

Google: bBW8Iy5SnQIC

Publisher: Univ of North Carolina Press

Published: 2010-01-15T03:17:42+00:00

âWill Uncle Sam Stand for This Cross?,â Chicago Defender, April 5, 1919.

The mere sight of an African American veteran in uniform sometimes proved sufficient to spark violence. Discharged black soldiers, especially those with little means, often returned home with nothing other than their army-issued clothes. More than simply an article of dress, the uniform connoted authority, power, manliness, and respect, a fact not lost on black servicemen and southern whites alike. Wearing the uniform thus constituted a bold act of defiance on the part of black veterans as an assertion of their citizenship and manhood. For these reasons many white southerners insisted that when African American troops returned to the South, they did so out of uniform, a plea that ignored the War Department's policy of allowing soldiers to wear their military fatigues for up to three months after discharge.69 White vigilantes often took matters into their own hands. In its April 5, 1919, issue, the Chicago Defender ran an announcement alerting black veterans of the war to reports of servicemen being stopped at southern railroad stations and âdisrobed of their uniforms to keep them from marching through the streets.â70 Alabama sharecropper Ned Cobb similarly recalled stories of discharged African American troops being met at southern train stations and subsequently forced to remove their uniforms by white mobs.71 In robbing returned soldiers of their uniforms, racist whites attempted to also rob them of their civic value, dignity, and very identity as veterans of the U.S. Army.

Twenty-four-year-old Daniel Mack experienced this pain and humiliation firsthand. Mack worked as a farmer in Shingler, Georgia, before his call into the army. Two years later and after having served overseas with the 365th Infantry Regiment, Mack returned home. On April 5, 1919, Mack, dressed in his army uniform, and a friend ventured into the town of Sylvester, a short distance from Shingler and the nearest commercial district. It was a busy Saturday afternoon, and people from the surrounding countryside crowded the streets. While walking, Mack inadvertently brushed against a white passer-by, Samuel Haman.72 An aggrieved Haman struck Mack in response to this slight of racial custom, knocking him off the sidewalk. Mack, emboldened by his time in the army, retaliated. A fight ensued, leading to his arrest. At his arraignment the following Monday morning, Mack pleaded not guilty to assault, punctuating his plea with the statement, âI fought for you in France to make the world safe for democracy. I don't think you treated me right in putting me in jail and keeping me there, because Iâve got as much right as anybody else to walk on the sidewalk.â Taken aback by his insolence, the presiding justice of the peace admonished him with the reminder that âthis is a white man's country and you don't want to forget it.â Mack received a sentence of thirty days on a chain gang and was led away in shackles.

In both the black and white communities, emotions ran high. African Americans were appalled by the miscarriage of justice perpetrated upon a veteran, one of their heroes.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4289)

Never by Ken Follett(3930)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3365)

Oathbringer (The Stormlight Archive, Book 3) by Brandon Sanderson(3123)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3062)

Will by Will Smith(2903)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2348)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2319)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2299)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2211)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2186)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(2031)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1833)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1832)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1746)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1707)

Kingdom of Ash by Maas Sarah J(1661)

515945210 by Unknown(1660)

443319537 by Unknown(1541)