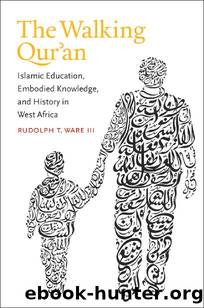

The Walking Qur'an (Islamic Civilization and Muslim Networks) by Rudolph T. Ware III

Author:Rudolph T. Ware III [Ware, Rudolph T. III]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2014-06-16T00:00:00+00:00

Girls at a Qurʾan school in Dakar, Senegal, from a mid-twentieth-century postcard.

The school appears in her exhortation as the site where girls learned how to fulfill basic religious obligations, reaffirming the daaraâs central role in practical instruction. But this passage also draws attention to the heavy household burdens that curtailed the scholarly aspirations of many female Qurʾan students. Niass and others took their schooling much further, but for most girls, the daaraâs mission ended with the rudiments of faith and preparation for domestic life.

Thus Senegalese sociologist Yaya Wane could still generalize in the ethnographic present of the 1960s: âThe prolonged study of the Qurʾan is only incumbent on the boys of the free castes. . . . Whereas for the boys of the professional or servile castes and the girls of all castes, generally the social collective esteems that their stay at the koranic school can be of short duration, because the former have a métier to learn, and the latter must be prepared for their conjugal destination.â55 Whatever the decree of the âsocial collectiveâ (freeborn males), twentieth-century students of all backgrounds had more opportunities than had been available in the past to pursue serious instruction. While there are few reliable sources for statistical analyses in recent periods, statistics from neighboring countries and direct observations suggest that by the first decade of the twenty-first-century, between a third and half of all Qurʾan students were girls. If this is true, then much of the increase in feminine attendance likely has come from girls from the low-status groups attending Qurʾan schools in unprecedented numbers.

CHANNELING THE DEMAND

Changing gender ratios are part of an overall increase in accessibility of Qurʾan schooling for people who were generally considered second-class Muslims in earlier eras. The descendants of slaves in particular have received greatly improved access to religious education over the past century. The multitude of slaves who fled to Murid settlements in central Senegal seeking instruction and Islamic legitimacy in the orderâs daaras has been well documented elsewhere.56 The slaves and subalterns who fled to the relative anonymity of cities and towns and sought Islamic legitimacy in TijÄnÄ« structures have been less well documented, but a number of scholars have made arguments that echo Lucie Colvin: âDuring the colonial period, when the towns became a refuge for low status persons escaping rural masters, the TijÄniyya recruited freely.â57 The Sufi orders sought to deemphasize social origins, laying new stress on equality before God. They also provided an entirely new framework of social hierarchy. Moreover, they did so in delocalized spaces. Structures of caste and slavery were particularly well suited to the old agrarian village order. Murids established new villages, towns, and even cities in agricultural areas of the Senegambian interior. TijÄnÄ«s made formidable inroads in colonial cities and towns such as Dakar, Kaolack, Kebemer, Tivaouane, and Saint-Louis. The Sufi orders did not eradicate older orders of âcasteâ and hierarchy but made them less salient.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Hadith | History |

| Law | Mecca |

| Muhammed | Quran |

| Rituals & Practice | Shi'ism |

| Sufism | Sunnism |

| Theology | Women in Islam |

The History of Jihad: From Muhammad to ISIS by Spencer Robert(2216)

Nine Parts of Desire by Geraldine Brooks(2014)

The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion by Daniel Spicer(2000)

The First Muslim The Story of Muhammad by Lesley Hazleton(1891)

The Essential Rumi by Coleman Barks(1641)

The Last Mughal by William Dalrymple(1575)

Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth-Century Muslim Between Worlds by Davis Natalie Zemon(1547)

1453 by Roger Crowley(1511)

by Christianity & Islam(1354)

God by Aslan Reza(1339)

Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources by Martin Lings(1309)

A Concise History of Sunnis and Shi'is by John McHugo(1279)

Magic and Divination in Early Islam by Emilie Savage-Smith;(1205)

The Flight of the Intellectuals by Berman Paul(1187)

No God But God by Reza Aslan(1166)

Art of Betrayal by Gordon Corera(1136)

What the Qur'an Meant by Garry Wills(1124)

Getting Jesus Right: How Muslims Get Jesus and Islam Wrong by James A Beverley & Craig A Evans(1083)

The Third Choice: Islam, Dhimmitude and Freedom by Durie Mark & Ye'or Bat & Bat Ye'or(1071)