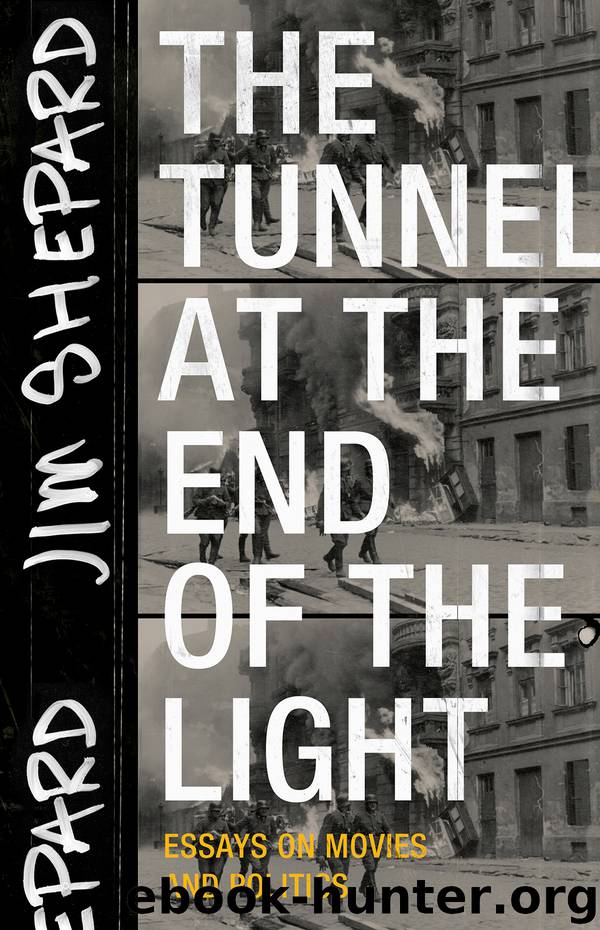

The Tunnel at the End of the Light by Jim Shepard

Author:Jim Shepard

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Tin House Books

BABETTE’S FEAST AND THE WEEPIE

As a kid back in the Pleistocene, I was periodically dumped in front of the TV after school, and that meant either talk shows, soaps, or movies, and every so often I’d tumble out of a run of rubber-suited monster pictures—Reptilicus, Gorgo, Night of the Blood Beast—into another equally bizarre afternoon genre: the “woman’s picture,” or “weepie,” as Variety called them.

We recognize the territory when we channel surf into it: Lana Turner in that enameled ’50s technicolor, facing away from some knit-browed and forgettable male; Barbara Stanwyck looking star-crossed and miserable as she peers over a fence in the rain at her own daughter’s wedding; Joan Fontaine just staying put, her whole gestalt a perfect figure for submissiveness. An overstated string section to help us register the heartache.

The stories trundled through decades of forbearance: slow-moving mile-long freight trains of self-denial. All those women gave up what they most wanted for somebody else’s sake. Which meant their movies centered on events that didn’t happen: the singing career that wasn’t begun, the wedding that didn’t occur, the meeting in the park that never came off, the key phrase left unspoken. Which made for movies obsessed with the life not lived: a weird negative space of the never-was and the might-have-been. Even the titles gave it away: Written on the Wind, All I Desire, Since You Went Away, There’s Always Tomorrow, Imitation of Life.

This genre received some public reconsideration in 2003 because of Todd Haynes’s Far from Heaven, with its four Academy Award nominations and critical support on both coasts. While Heaven was not as jaw-droppingly mechanical a project as Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake of Psycho a few years before, the debate around it centered on just what to make of the extremity of its stylistic self-consciousness. It was either a reconstruction of or a paean to Douglas Sirk’s movies, particularly All That Heaven Allows, and Sirk was the great master of the astoundingly overwrought and the weirdly bottled up when it came to American suburban white emotions.

We still gape today at such movies partly because of the way they enshrine what seems to us an antiquated masochistic selflessness, if not self-eradication. They all seem to feature a woman who wants in some way to express herself, to make herself known, plopped down in a story that demonstrates the impossibility of realizing that desire. Again, go back to the titles: Letter from an Unknown Woman, The Old Maid, Madame X.

All of that should sound familiar to anyone who’s read one of those steamer trunk–sized 18th-century novels, like Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, that feature 1,500 pages of private feelings informed by pious, if not puritan, codes of morality and conscience colliding with innermost desires. Conflicts, in other words, not so much between heart and head as heart and soul.

If that was the choice, it wasn’t too hard to figure out which we were supposed to root for. Jeez. Heart (and by implication, body) or soul: Which was ultimately more important?

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4975)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4565)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(4236)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4106)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3969)

Schaum's Quick Guide to Writing Great Short Stories by Margaret Lucke(3384)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3327)

What If This Were Enough? by Heather Havrilesky(3314)

The Day I Stopped Drinking Milk by Sudha Murty(3204)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2958)

Letters From a Stoic by Seneca(2801)

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bryson Bill(2700)

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde(2614)

Insomniac City by Bill Hayes(2561)

Feel Free by Zadie Smith(2485)

Upstream by Mary Oliver(2395)

Miami by Joan Didion(2375)