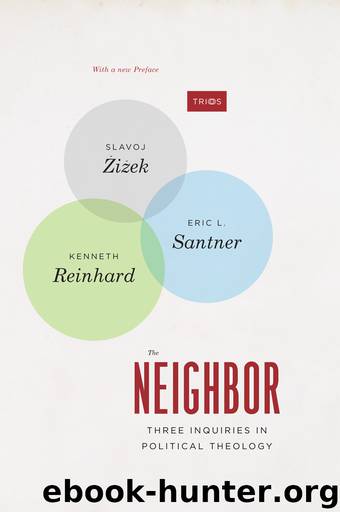

The Neighbor by Žižek Slavoj; Santner Eric L.; Reinhard Kenneth

Author:Žižek, Slavoj; Santner, Eric L.; Reinhard, Kenneth [Žižek, Slavoj]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2005-09-03T16:00:00+00:00

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK

Neighbors and Other Monsters: A Plea for Ethical Violence

Critique of Ethical Violence?

In one of his stories about Herr Keuner, Bertolt Brecht ruthlessly asserted the Platonic core of ethical violence: “Herr K. was asked: ‘What do you do when you love another man?’ ‘I make myself a sketch of him,’ said Herr K., ‘and I take care about the likeness.’ ‘Of the sketch?’ ‘No,’ said Herr K., ‘of the man.’”1 This radical stance is more than ever needed today, in our era of oversensitivity for “harassment” by the Other, when every ethical pressure is experienced as a false front of the violence of power. This “tolerant” attitude fails to perceive how contemporary power no longer primarily relies on censorship, but on unconstrained permissiveness, or, as Alain Badiou put it in thesis 14 of his “Fifteen Theses on Contemporary Art”: “Since it is sure of its ability to control the entire domain of the visible and the audible via the laws governing commercial circulation and democratic communication, Empire no longer censures anything. All art, and all thought, is ruined when we accept this permission to consume, to communicate and to enjoy. We should become pitiless censors of ourselves.”2

Today, we seem effectively to be at the opposite point from the ideology of 1960s: the mottos of spontaneity, creative self-expression, and so on, are taken over by the System; in other words, the old logic of the system reproducing itself through repressing and rigidly channeling the subject’s spontaneous impetuses is left behind. Nonalienated spontaneity, self-expression, self-realization, they all directly serve the system, which is why pitiless self-censorship is a sine qua non of emancipatory politics. Especially in the domain of poetic art, this means that one should totally reject any attitude of self-expression, of displaying one’s innermost emotional turmoil, desires, and dreams. True art has nothing whatsoever to do with disgusting emotional exhibitionism—insofar as the standard notion of “poetic spirit” is the ability to display one’s intimate turmoil, what Vladimir Mayakovski said about himself with regard to his turn from personal poetry to political propaganda in verses (“I had to step on the throat of my Muse”) is the constitutive gesture of a true poet. If there is a thing that provokes disgust in a true poet, it is the scene of a close friend opening up his heart, spilling out all the dirt of his inner life. Consequently, one should totally reject the standard opposition of “objective” science focused on reality and “subjective” art focused on emotional reaction to it and self-expression: if anything, true art is more asubjective than science. In science, I remain a person with my pathological features, I just assert objectivity outside it, while in true art, the artist has to undergo a radical self-objectivization, he has to die in and for himself, turn into a kind of living dead.3

Can one imagine a stronger contrast to today’s all-pervasive complaints about “ethical violence,” in other words, to the tendency to submit to criticism ethical injunctions that “terrorize” us with the brutal imposition of their universality.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7354)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7137)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6800)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6621)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5791)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5519)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5196)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4456)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4314)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4279)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4264)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4257)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4133)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4012)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3969)