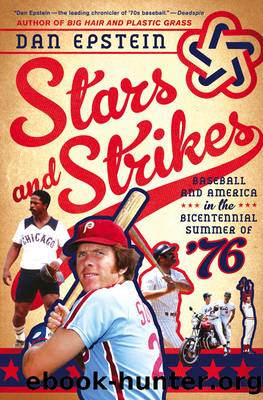

Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ‘76 by Dan Epstein

Author:Dan Epstein [Epstein, Dan]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: 20th Century, Baseball, History, Non-Fiction, Sports & Recreation, United States

ISBN: 9781250034380

Google: XtwjAwAAQBAJ

Amazon: B00G1IWXK0

Publisher: St. Martin's Press

Published: 2014-04-28T23:00:00+00:00

8.

Afternoon Delight

(July 1976)

After years of buildup, hype, and anticipation, there was no way that America’s 200th birthday party was going to be anything less than a gloriously, gaudily, ridiculously over-the-top affair. President Ford urged Americans everywhere to “break out the flag, strike up the band, light up the sky” for the star-spangled occasion. But from Mars Hill, Maine—where the first rays of dawn’s early light hit the continental U.S. at 4:31 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time—to the harbor village of Pago Pago in American Samoa, flag-waving, marching bands, and fireworks constituted just a fraction of the festive fun on the agenda for July 4, 1976.

The marquee event of the nationwide celebration (or at least the one that presented the most impressive visual spectacle to the many millions watching it in person and on television) was Operation Sail, which featured the arrival of 212 sailing vessels from around the world (including a full-scale model of Christopher Columbus’s Santa María) in New York Harbor. The Tall Ships were met by an estimated 30,000 smaller crafts ranging from yachts to kayaks—as well as the 80,000-ton aircraft carrier USS Forrestal, which served as both host ship to the flotilla and viewing station for some 3,000 dignitaries—including President Ford (who’d already made appearances in Valley Forge and Philadelphia earlier in the day) and most of his cabinet, various members of Congress, and Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco—before sailing majestically up the Hudson River.

In Boston, two replicas of lanterns used to signal Paul Revere’s midnight ride of 1775 were lit using an electrical impulse generated from the light of the star Epsilon Lyrae, which scientists believed to be positioned exactly 200 light-years from Earth. (The light currently seen from the star would therefore have been generated around the time that John Hancock put his “John Hancock” on the Declaration of Independence.) Some 400,000 Bostonians gathered along the banks of the Charles River on the evening of the Fourth to hear a Boston Pops concert; in nearby Foxboro, another 60,000 turned out to see British pop star Elton John—whose new duet with Kiki Dee, “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart,” was rocketing up the pop charts—perform at Schaefer Stadium. John, whose appreciation for his sizable American audience was surpassed only by his love for all things camp, appeared onstage as a silver-robed Statue of Liberty. Some 3,000 miles away, the Ramones returned the cultural exchange, playing the first overseas gig of their career supporting the Flamin’ Groovies at London’s Roundhouse, where they served up their stripped-down, speeded-up brand of New York punk rock (as well as dozens of promotional plastic baseball bats, in reference to their anthem “Beat on the Brat”) to a crowd comprising a substantial segment of London’s burgeoning punk scene.

Every municipality in America, large and small, seemed to have something extravagant planned for the Fourth. Washington, D.C., lit up the night with the largest fireworks display in U.S. history, a 33-and-a-half-ton affair detonated by Etablissements Ruggieri, the venerable French fireworks firm that had once designed a display that entertained Thomas Jefferson during his 1786 Paris visit.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4293)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Liar's Poker by Michael Lewis(3441)

The Ultimate Backcountry Survival Manual by Aram Von Benedikt; Editors of Outdoor Life;(3257)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

The Partner by John Grisham(2395)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2323)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

Taste by Kris Bryant(1859)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1842)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1839)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1722)

Never Finished: Unshackle Your Mind and Win the War Within by David Goggins(1703)

515945210 by Unknown(1660)

Why We Love Baseball by Joe Posnanski(1612)

The Arm by Jeff Passan(1605)

443319537 by Unknown(1545)

The Dodgers by Schiavone Michael;(1527)

The Yogi Book by Yogi Berra(1521)