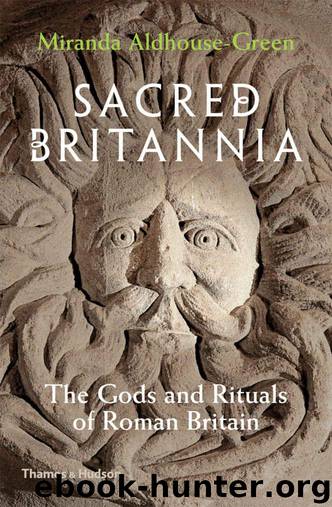

Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain by Aldhouse-Green Miranda

Author:Aldhouse-Green, Miranda [Aldhouse-Green, Miranda]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Thames and Hudson Ltd

Published: 2018-06-27T16:00:00+00:00

Ravens and ‘bird-men’

‘Conare took his sling and stepped from his chariot and followed the great speckled birds until he reached the ocean. The birds went on the waves, but he overtook them. The birds left their feather hoods and turned on him with spears and swords; one bird protected him, however, saying, “I am Nemglan, king of your father’s bird troop. You are forbidden to cast at birds, for, by reason of your birth, every bird is natural to you.”’35

Nemglan appears in Irish mythology as a ‘bird-man’, probably a shaman who assumed an animal-persona, the better to communicate with the spirit world. The speckling of his and his fellow birds’ plumage is telling for, as we have seen in the description of the future-telling Fedelma, dappling was the signature of a ‘two-spirit’ being. Nemglan’s fellow bird-man was a blind Druid named Mog Ruith whose physical incapacity allowed his inner sight to flourish and to be used to see into the future.36 The ‘prohibition’ placed upon Conare by Nemglan resonates with the doctrine of bodily rebirth mentioned by Classical chroniclers as preached by Gallic Druids (see Chapter 10).

The Aylesford ‘horse-people’ wore elaborate headdresses that look as if they were made from feathers. There is some circumstantial evidence for the use of plumage for ceremonial headgear too, from Iron Age ritual deposits at hillforts in southern England. The practice of reusing decommissioned grain silos as foci for votive offerings has long been known at sites such as Danebury and Winklebury.37 Deposits often include the entire or partial bodies of humans and animals, and by far the most common of the latter belonged to domestic species: cattle, sheep and pigs, kept as livestock, plus significant numbers of horses and dogs, often found together. But the only wild creature to occur in any quantity is the raven, and this has been explained in terms of its underworld connotations, based on its blackness and its carrion-feeding habits.

Recent research on Iron Age and Romano-British bird-burials, including the Danebury burials and a group of corvids found in shafts in the centre of Roman Dorchester,38 has suggested another explanation for the presence of ravens in these pit-deposits, proposing that these creatures might have been exploited for their feathers, perhaps for use in religious ceremonies.39 The reason for proposing this stems partly from their singling out for special, arguably ritual, deposition in deep underground locations, but the most compelling argument for such a thesis is the revelation that some ravens had their wings and feathers removed after they had been killed, but were otherwise left intact. The selection of ravens for such treatment might be because of the large, glossy feathers that would make ideal and striking headdresses, but also because of the raven’s distinctive ‘voice’, one that can mimic and learn simple human speech, its longevity, its memory and its reputation for being able to foretell the future (this last perhaps because they were quick to spot bloodshed and fly to the scene to scavenge). Moreover, ravens are

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Fall of Carthage by Adrian Goldsworthy(1092)

The Mysteries of Mithra by Cumont Franz(1045)

Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain by Aldhouse-Green Miranda(889)

The Ghosts of Cannae: Hannibal and the Darkest Hour of the Roman Republic by Robert L. O'Connell(864)

The Satyricon by Petronius(840)

Selected Political Speeches by Marcus Tullius Cicero(837)

Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric by Michael Kulikowski(817)

The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy by Adrienne Mayor(815)

Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch(805)

Letters from a Stoic (Classics) by Seneca(772)

Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic by Tom Holland(735)

In Defence of the Republic by Cicero(725)

Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome by Everitt Anthony(718)

Delphi Complete Works of Cicero by Cicero(684)

The Roman History by Cassius Dio(656)

Letters from a Stoic by Seneca(620)

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by David Womersley(618)

The Twelve Caesars (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius & Robert Graves(615)

The Spartacus War by Strauss Barry(577)