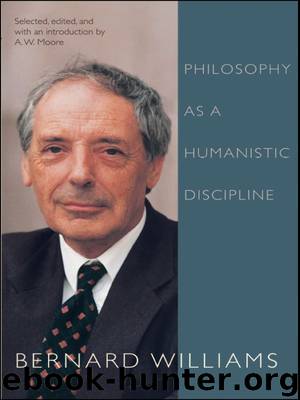

Philosophy as a Humanistic Discipline by Williams Bernard; Moore A. W.; Moore A. W. W

Author:Williams, Bernard; Moore, A. W.; Moore, A. W. W.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2008-09-19T16:00:00+00:00

TEN

Values, Reasons, and the Theory of Persuasion

1. INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL REASONS

The distinction that I shall discuss under this title is not, strictly speaking, a distinction between two kinds of reason, but rather a distinction between two kinds of claim that can be made about what an agent A has reason to do. The statement ‘A has reason to X’ receives an internal interpretation if it is taken to mean ‘A could arrive at a decision to X by sound deliberation from his existing S’, where S is A’s existing set of desires, preferences, evaluations, and other psychological states in virtue of which he can be motivated to act. An external interpretation does not carry this implication. (Throughout the discussion I adopt the simplifying assumption that ‘A has reason to X’ means ‘A has more reason to X than to do anything else’; additional qualifications would in fact enable one to drop this restriction.) A view that I have expressed elsewhere (Williams 1980; 1989; 1995b), and will defend here, is that if ‘A has reason to X’ has a distinctive sense, then it must receive the internal interpretation; in simplified form, the only reasons for action are internal reasons. I do not deny that ‘A has reason to X’ can entirely intelligibly be asserted without this implication. The claim is merely that when it is so asserted, it means something that could be expressed by a different kind of sentence, for instance to the effect that it is desirable that A should do the thing in question, or that we have reason to desire that A should do it. Only the internal interpretation represents the statement as distinctively a statement about A’s reasons. Relatedly, if a statement of this kind is true, and A declines to do the thing in question, what is called in question is A’s capacity in this connection to act rationally or reasonably. It would be too strong, for more than one reason, to say that in such circumstances A acts irrationally, but the line of criticism that will be appropriate in these circumstances will address itself to A’s performance as a rational or reasonable agent rather than to other deficiencies that he may have.

It is important to emphasize the variety of elements that are, on this view, to be included in the agent’s S. It does not contain merely inclinations or, again, egoistic motivations, and it can certainly contain dispositions associated with the agent’s recognition of various kinds of values. Moreover, it is not the case that everything in the agent’s S has already to be formed into preferences; and in so far as it is formed into preferences, those preferences do not necessarily have to satisfy formal conditions of completeness. There is no naturalistic reason, based on considerations of psychology or the philosophy of mind, to suppose that these indeterminacies are radically reducible, in particular to preference orderings that can be handled by Bayesian techniques. If there is a demand for such a reduction, it

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8404)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7356)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7137)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6800)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6621)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5791)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5520)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5196)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4456)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4315)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4280)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4264)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4258)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4133)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4013)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3970)