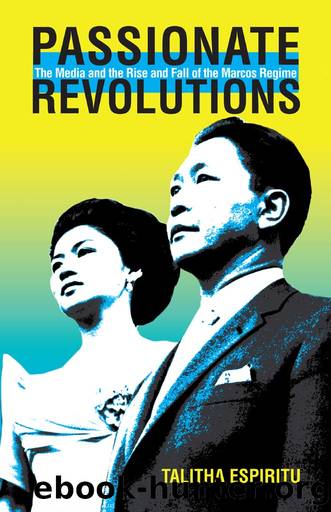

Passionate Revolutions by Talitha Espiritu

Author:Talitha Espiritu [Espiritu, Talitha]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Media Studies, Political Science, Colonialism & Post-Colonialism

ISBN: 9780896804982

Google: _SxzDgAAQBAJ

Publisher: Ohio University Press

Published: 2017-04-15T03:17:31+00:00

Chapter 5

THE MEDIA AND THE SECOND COMING OF THE FIRST QUARTER STORM

Marcosâs June 30, 1981, inaugural celebration was a made-for-TV spectacular dubbed âAko ay Pilipinoâ [I am the new Filipino]: Rites of the New Republic.â If the Marcos regime were to be believed, 30 million television viewers, or nearly three-fourths of the population, saw the live telecast of Marcosâs swearing in at the Luneta grandstand.1 Twenty-eight state visitors, including U.S. vice president George H. W. Bush, were present to watch an event that climaxed with a thousand-voice male chorus singing the âHallelujah Chorusâ from Handelâs Messiah. âAnd he shall reign forever and ever.â2

Panorama, the Sunday supplement to Manilaâs Bulletin Today, duly featured the inaugural. On the cover of the July 12, 1981, issue were three black-and-white photographs of the president, one in each of his inaugurationsâ1965, 1969, and 1981. Compared to the high production values of âAko ay Pilipino,â the Panorama cover seemed almost insipid. And, given the intense coverage that the inaugural had already received in the establishment press, nobody expected anything out of the ordinary from the magazine. But when editor Letty Jimenez-Magsanocâs story âThere Goes the New Society, Welcome the New Republicâ prompted the Ministry of Justice, the chairman of COMELEC, and the secretary-general of the KBL to threaten Bulletin/Panorama publisher Hans Menzi with âseditious libelâ (and thereby force Magsanoc to resign), the offending Panorama issue became an instant collectorâs item. But âit was more than that,â veteran journalist Marcelino B. Soriano points out. Magsanocâs swan song âmarked an awakening of the journalism profession.â3

Magsanocâs controversial article briefly mentions Presidential Decree 1737, issued in September 1980. The act authorized Marcos to direct the âclosure of subversive publications or other media of mass communications.â Magsanocâs reflexive dig at the legal measure intended to muzzle the media in the New Republic is followed by the ironic statement: âYet with all the awesome powers at his disposal, [Marcos] needed, he said, to go before the people âto be judgedâ on his performance in office for 16 consecutive years.â Hinting at the fraudulence of the election, Magsanoc would draw the full ire of the regime with the following concluding lines: âThe problem is a Marcos who with all his powers is powerless before corruption and the corruptors. It is a Marcos astride the same tired tiger (the discarded and discredited New Society) carrying on under a different name, the New Republic. If that continues, the Filipino, docile as he has been as the carabao [water buffalo] these 16 years cannot but give way and tear at the Republic.â4

Magsanocâs acerbic piece was a bomba. Largely dormant since the imposition of martial law, the bomba occasionally appeared in the crony media; but it was largely used to âexposeâ the nefarious activities of the elite opposition. Magsanocâs impudent digs at âcorruption and corruptorsâ within the regime was much more than a simple shift in bomba targets. The suggestion that the all-powerful Marcos was in fact âpowerlessâ called into question the very linchpin of Marcosâs national family.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2298)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2291)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2069)

Will by Will Smith(2041)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1765)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1570)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1570)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(1373)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1327)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1300)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1256)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1234)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(1227)

515945210 by Unknown(1207)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1109)

443319537 by Unknown(1072)

Works by Richard Wright(1018)

Going There by Katie Couric(991)