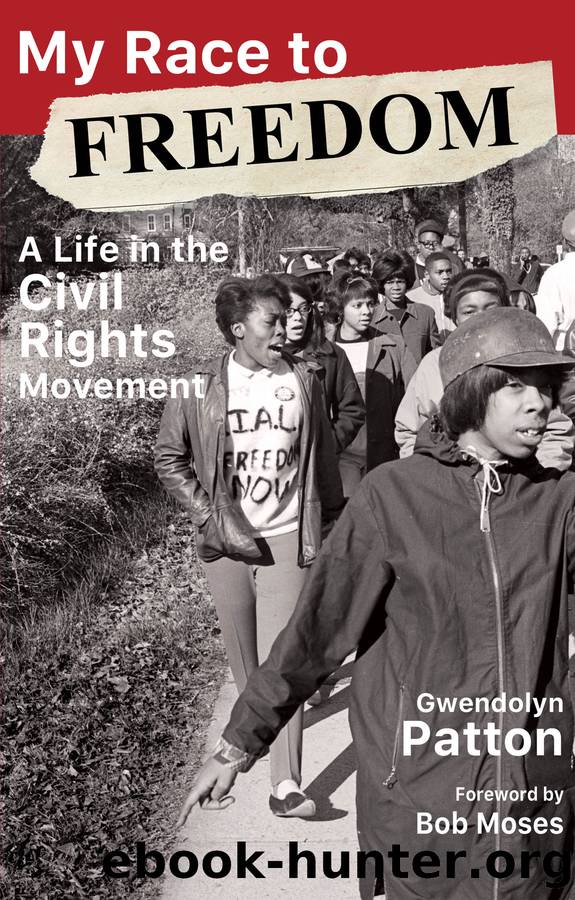

My Race to Freedom by Gwendolyn Patton

Author:Gwendolyn Patton

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781603064514

Publisher: NewSouth Books

Published: 2020-09-04T00:00:00+00:00

16

SNCC and Black/White Issues

Summer school resumed its regular routine of classes and picket lines in downtown Tuskegee. White exchange students from St. Olaf College of Minnesota and the University of Michigan were a visible critical mass within the student body. Charlene Kranz, a white coed from Washington, D.C., enrolled outright as a Tuskegee student; her father worked in the government and had ties with the Community Relations Program that mediated race relations in Tuskegee. Charlene had learned firsthand from her father about the Tuskegee student movement. She wanted to be part of it. Charlene and I became fast friends.

Tuskegee continued to be a staging area from which SNCC organizersâmainly brothers and two extraordinary sisters, Martha Presod and Gloria Larryâoperated in the Alabama Black Belt counties of Lowndes, Wilcox, Dallas, and Greene. In Macon County itself, leadership was mostly provided by Institute studentsâespecially Wendy and George Paris, Simuel Schultz, Eldridge Burns, Demetrius âRedâ Robinson, and others who grew up in Tuskegee.

Soon we saw an influx of northern white women who had remained in Mississippi after the 1964 Freedom Summer. Many said these white women were chasing SNCC black men. I couldnât have cared less. I recognized that some sisters will find some brothers absolutely incompatible for personal companionship, and vice versa. People should have the right and the freedom to choose their own companions. However, the problem with many white women, after they coupled with their black companions, was their âWhite African Queen Syndromeâ and their arrogance to tell black people what we should do in our struggle for freedom. I knew it would be a matter of time before we would send these white women packing. If they insisted on staying in Tuskegee, then their contribution must be one of listening and learning from the grassroots people, not one of talking and directing.

James Forman asked me to serve as a guide for some of these white women. We were driving on Highway 80 through Lowndes County where there was not one black registered voter although the county was 90 percent black. Many residents had been evicted from the land they worked on and tenant houses. They were living in tents because they dared to try to register to vote after the Selma March.

âSlow down the car,â one of the white women said. âThe cotton is so beautiful. It looks like clouds on earth.â

I said nothing but I was incensed. It was clear that these women did not comprehend the relationship of black people and cotton that was the economic foundation for slavery and then for sharecropping and tenantry. While white plantation ownersâ children played and frolicked during the summers, black children were forced into the blistering heat to chop and hoe cotton. In October, black children were dismissed from the shabby county schools to pick cotton with sacks on their backs. In March, the children were dismissed from school to plant cotton.

When we returned to campus, I immediately sought out James Forman. âThese white heifers have to go,â I said.

âGwen, you have a latent hostility for white women!â

âLatent?â I retorted in a huff.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Blood and Oil by Bradley Hope(1558)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1418)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1383)

Daniel Holmes: A Memoir From Malta's Prison: From a cage, on a rock, in a puddle... by Daniel Holmes(1329)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(1313)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1294)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1167)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(1154)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(1145)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1130)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(1125)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(1117)

Cleopatra by Alberto Angela(1093)

A Woman by Sibilla Aleramo(1092)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(1074)

John (Penguin Monarchs) by Nicholas Vincent(1068)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(1024)

Reading for Life by Philip Davis(1023)

The Life of William Faulkner by Carl Rollyson(981)