London's News Press and the Thirty Years War by Jayne E.E. Boys

Author:Jayne E.E. Boys [Boys, Jayne E.E.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Modern, 17th Century, Language Arts & Disciplines, Journalism, Social Science, Media Studies

ISBN: 9781843839347

Google: vxIABQAAQBAJ

Publisher: Boydell & Brewer Ltd

Published: 2014-01-15T04:05:43+00:00

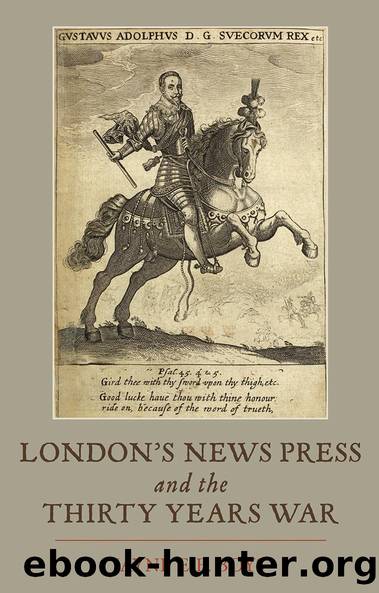

Plate 4. Page 142 of The Swedish Intelligencer. The first part (1632) which, as it boasted, was revised and augmented for the third time. It illustrates the level of detail and editorâs extensive comments (intended for English and Scottish readers) in both the text and margin. Crossing the River Lech, in April 1632, was (as noted) one of Gustavus Adolphusâs greatest achievements, allowing him to enter Munich in May.

At the end of the decade Lady Brilliana Harley, writing to her son in Oxford, looked forward to the resumption of regular news publication following the grant of a patent to Butter and Bourne in December 1638.33 She was probably disappointed by the product when it arrived. The next series marked a distinct regressive step. Dutch and German publications were reproduced without any editorial contribution in London that might enhance their appeal. They had little to commend them to popular taste. They were repetitious, giving telegram-like reports of the same news from all directions. A reader might have been fortunate to find one interesting report with eyewitness detail or a story line in a weekâs batch of three issues. There was no analysis and no engagement with readers in dialogue. We only know that, after an initial period of good sales that sustained an initially high output, they could not compete with the growing market in short ephemeral pamphlets appearing in London. Readers voted with their pennies and foreign news ceased to be a viable enterprise. As Butter explained, âif a number shall be vented weekly, to recompence the charge, we shall continue them; if not, we shall be forced to put a period to the Presseâ.34

In the more vociferous decade of the 1640s, there was a transformation in the circumstances for public debate. A multitude of pamphlets brought contemporary domestic as well as foreign issues into print. Wallington and Rousâs reflections showed how the increase in print in 1640â2 at times seemed to readers overwhelming, adding to unease and uncertainty in the heightened climate of âanxiety, mistrust and fearâ. Meanwhile, those who left no written record, but could read or hear the news by gathering around someone who could read it aloud, were more visibly participating in public discussion. Artisans, apprentices, chapmen and hawkers took politics out of doors into the streets and theatres, and people read and argued over pamphlets while standing in stationersâ shops. (In 1642, one such altercation even came to the attention of the House of Commons.)35 Controversial debate appeared in what McKenzie has called âa form of communicative interchangeâ that was speech-like in the way it was presented in print and gives us an exceptional view of contemporary opinions and arguments as they emerged. Readers could respond as writers. Peacey has demonstrated the propaganda dimensions of this dialogue, probing the heady mixes of political and commercial motives behind publications. He argued that there was a growing sophistication in ânews managementâ by the proponents of both parliamentary and royalist views. There was also a greater awareness of the tactics the press employed as the decade progressed.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Never by Ken Follett(2872)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2289)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2264)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2058)

Will by Will Smith(2032)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1760)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1564)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1562)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(1368)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1321)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1295)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1251)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1231)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(1218)

515945210 by Unknown(1205)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1106)

443319537 by Unknown(1069)

Works by Richard Wright(1017)

Going There by Katie Couric(988)