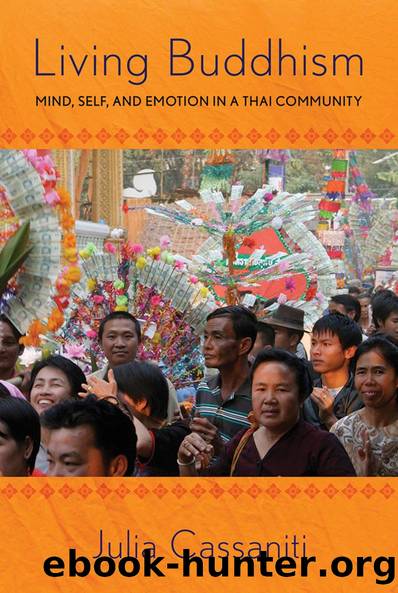

Living Buddhism by Julia L. Cassaniti

Author:Julia L. Cassaniti [Cassaniti, Julia L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Anthropology, Cultural & Social, Religion, Buddhism, Rituals & Practice, History, Asia, Southeast Asia

ISBN: 9781501700972

Google: cxTRCgAAQBAJ

Publisher: Cornell University Press

Published: 2015-12-18T03:30:04+00:00

Letting Go in a World of Change

Attending to letting go (as focused on nonattachment) helps to make sense of otherwise difficult-to-understand behaviors and experiences in the course of everyday life in Buddhist Thailand, not just in Mae Jaeng. Charles Keyes (1985) offers one such example when he describes a woman called Mrs. K in Northeastern Thailand who was grief-stricken by the death of her mother. After the villagers construct a large bell tower in the center of the village and perform a rite that, we are told, helps the souls of the deceased progress to a new incarnation, she feels better. Keyes explains that it is the ritual action qua ritual action that helps. He suggests that rituals and rites everywhere help people to deal with grief at loss. A year after the rite, Keyes tells us, Mrs. K is flourishing. But why a rite to send the soul of Mrs. Kâs mother on, and not another rite? Maybe any rite would have worked, but people chose this one. Keyes tells us that as the souls of the deceased were able to progress to a new incarnation, they would be âtroubled no longer.â Paying attention to the role of attachment in ideas about well-being helps to make sense of why. As for most untimely deaths in Thailand, the souls of the deceased are ânot yet ready for rebirthâ; they continue to have attachments to the living, and the living to them. The souls of the deceased and the mind of Mrs. K were tied up together. In the interpersonal construction of affect (interpersonal even after death), Mrs. K was creating emotions that were attached to her mother. The rite worked because in effect it released Mrs. Kâs mental bond and âallowedâ her mother to continue on; it also âallowedâ Mrs. K herself to let go of her attachment.

Nancy Eberhardt (2006) relates a similar incident of loss in a Shan village in Northern Thailand in which a young woman named Nang and her daughter Ying were killed in a lightning storm. Nangâs family and friends were fearful of feelings of attachment to the deceased, and it played out in their emotions. Eberhardt tells us that Nangâs niece would not say âI am sadâ at the passing, but âI feel pity for them,â a sentiment that indicates less emotional attachment on behalf of the speaker to the deceased. People told me about attachments to the dead often in interviews. They usually explained the danger as the deadâs attachment to the living. But the danger is twofold: it is also the fear of attachments of the living to the dead. Mourning rituals in Thailand work to help detach emotional feelings, thereby âlettingâ the attachment one has to a loved one âgo.â

This letting go can be found even in activities that seem on the surface not related at all. One afternoon well into my time in Mae Jaeng I showed up at Gaew and Senâs shop, and neither of them was around. âWhere are

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2299)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2291)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2069)

Will by Will Smith(2042)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1765)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1571)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1570)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(1373)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1327)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1300)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1256)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1234)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(1227)

515945210 by Unknown(1208)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1109)

443319537 by Unknown(1072)

Works by Richard Wright(1018)

Going There by Katie Couric(991)