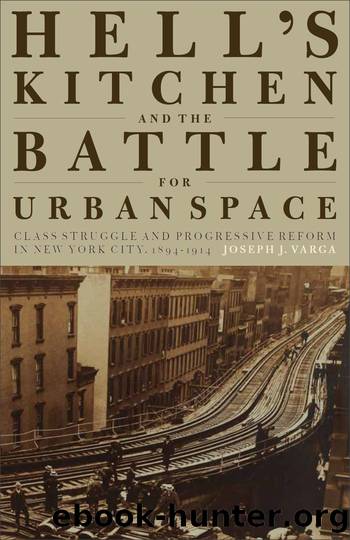

Hell's Kitchen and the Battle for Urban Space: Class Struggle and Progressive Reform in New York City, 1894-1914 by Joseph J. Varga

Author:Joseph J. Varga [Varga, Joseph J.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Political Science, Public Policy, City Planning & Urban Development

ISBN: 9781583673485

Google: MeMoAAAAQBAJ

Amazon: 1583673482

Publisher: NYU Press

Published: 2013-05-01T03:06:43.319827+00:00

For the West Side Irish, connections to Ireland, in the form of relatives and cultural memory, provided the framework for the production of local spaces of ethnic identity. As Ireland experienced numerous instances of struggle with England in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the cause of Home Rule and anti-English settlement served as rallying points to unite ideologically opposed groups. Whereas larger organizations such as Clan na Gael were primarily the reserve of the more well-off members of the New York Irish diaspora, county clubs, such as the Donegal Menâs Club and its Ladies Auxilliary, which met in Hellâs Kitchen, were largely the preserve of the Irish working class.193 County clubs created spaces not only for political activity, as when the clubs united to oppose the peaceful mediation of U.S.âBritish disputes in 1896, but were also places where business connections could be made. Though the majority of members were drawn from the working classes, county clubs also attracted a good number of Irish professionals and small business owners, and became places where a good carpenter could connect with a local contractor. The county clubs further contributed to the expansion of Irish ethnic space through participation in sports. As Manhattan clubs grew in size, they pooled their resources in 1897 to purchase land in the Laurel Hill section of Queens. There they built Celtic Park, originally set up to provide grounds for the traditional Irish sports of curling and Irish football. Only a ten-minute train ride from the Manhattan ferry terminal in Long Island City, Celtic Parkâs surrounding environs quickly became an Irish enclave, housing working-class and professional Irish leaving Manhattan in search of better living conditions.194

The Irish ethnic press was also utilized as a weapon to defend the Irish New York community against racist slurs, and to identify political friend and foe. William Randolph Hearst and his paper, the Evening Journal, came in for particular attention and vitriol in the Gaelic American for âslursâ against Irish women, and reformers like Dr. Charles Parkhurst were often singled out for their characterizations of the Irish as monolithic, despised, and inebriated. The New York Sun, the ârecognized organ of the English in New York, although owned by a Jew,â appeared as a weekly foil in the Irish American, and its bias was answered swiftly and decisively. Even fellow Catholics were called on the carpet, as when the Gaelic American conducted an ongoing campaign between 1900 and 1905 to end the âcaricaturing of the Irishâ at Catholic street fairs. But the Irish ethnic press did not only defend ethnicity. It promoted the Democratic Party in local elections, objecting especially to the âtributeâ paid by Irish city dwellers to upstate interests. Irish trade union papers were particularly apt to promote homeownership, often framing the issue in class terms, defending the right of the âtrades manâ to own his own home.

Churches were obvious places of ethnic and religious solidarity, as well as meeting places and nodal points for many residents. For the Irish, St. Malachyâs on Eleventh Avenue and 40th Street, and St.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Never by Ken Follett(2896)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2302)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2299)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2078)

Will by Will Smith(2047)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1769)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1574)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1572)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(1381)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1336)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1302)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1257)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1239)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(1235)

515945210 by Unknown(1212)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1111)

443319537 by Unknown(1077)

Works by Richard Wright(1020)

Going There by Katie Couric(993)