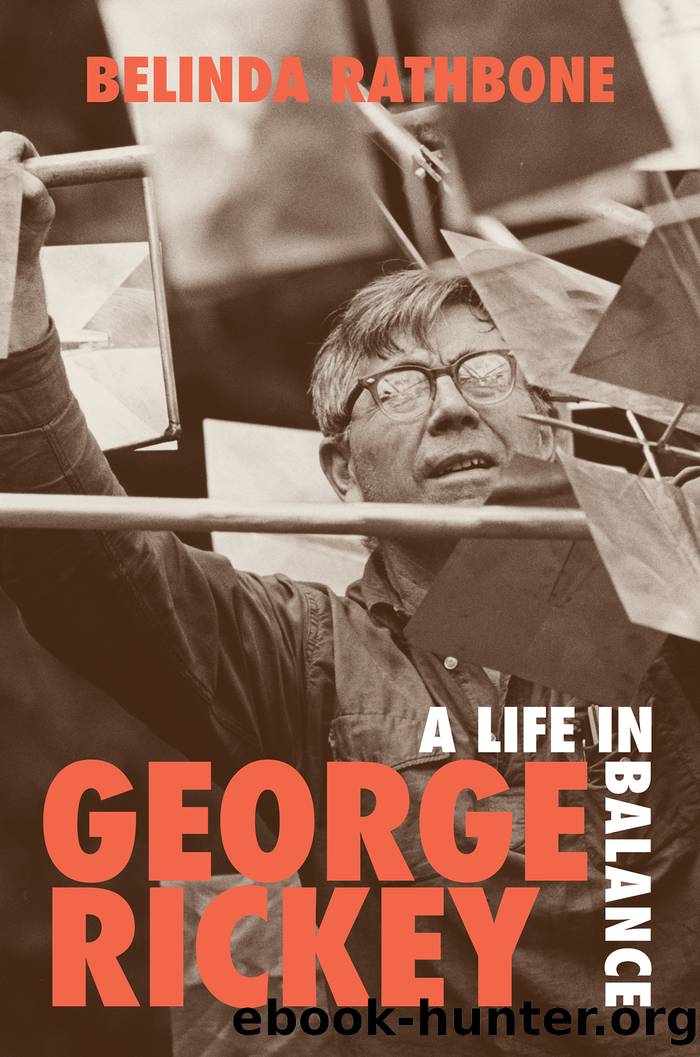

George Rickey by Belinda Rathbone

Author:Belinda Rathbone

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: David R. Godine, Publisher

Published: 2021-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

After a full ten years devoted to moving sculpture, Rickey had quite a lot to show for it. Experimenting with a variety of balancing acts, he was combining swings with pivots, rocking parts with fluttering parts, circles churning within circles, towers of pins upon pins. His sculptures flirted with instability but always returned to equilibrium. He composed with the hard rules of geometry while achieving a lightness and lyricism. Fascinated as he was by the spectrum of possibilities he was discovering in smaller works, it was time to rise to the challenge of outdoor sculpture, to meet nature head-on, to test his work against its forces, randomness, and wide-open spaces. It was time to enter a direct dialogue with the wind as an equal player in his design.

As he confided to Bill Dole, his friend from Olivet days, his vision of the next phase of his work, in the spring of 1959, was âmuch larger pieces for outdoors, which will be hard to show but will be important to have made.â7 He needed time off from his academic responsibilities to achieve those goals. âThe paramount problem is to produce, produce, produce,â he told Ulfert Wilke, âand to get the teaching into proper perspective.â If he sometimes doubted the validity of his undertaking, a favorable review from Bob Coates in the New Yorker of his latest show at the Kraushaar Galleries helped to strengthen his case to the public, as well as to himself. As he told Wilke, âI should take myself as seriously as [Coates] takes me.â8

In 1960 Rickey applied for the prestigious Guggenheim fellowship, with the prospect of devoting a year to creative work on âtechnical and design problems of kinetic sculpture.â Though he considered himself working in âa rather lonely idiom,â at the same time, as he wrote in his application, âI canât help seeing âKinetic Sculptureâ as one of the most apt and timely modes of expression of our epoch and I canât help feeling that I am working on the frontiers of it.â9 If granted the fellowship, he planned to spend most of his time in East Chatham, where he could by then claim to have a private and permanent studio. As he explained in his application, he would be developing ideas for smaller pieces as well as large-scale sculptures, taking on the new technical challenges that scaling up would involve.

His references for the grant came from a range of professional colleagues spanning the yearsâartist friends such as Philip Evergood and Ulfert Wilke and fellow teachers such as Harry Prior, a colleague from Olivet, who had become director of the American Federation of Arts in New York. Two glowing references came from professors at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in Troy, New York, an institution Rickey already had his eye on for possible future employment: Edward Millman, whom he had known in Bloomington was a visiting professor of art, and Don Mochon, an old friend from Woodstock, who was a professor of architecture. All had positive things

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Body Art & Tattoo | Calligraphy |

| Ceramics | Conceptual |

| Digital | Erotic |

| Film & Video | Glass |

| Graffiti & Street Art | Illuminations |

| Installations | Mixed Media |

| Mosaic | Prints |

| Public Art | Video Games |

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11840)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8916)

The Red Files by Lee Winter(3417)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3310)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3303)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2884)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2673)

Champions of Illusion by Susana Martinez-Conde & Stephen Macknik(2453)

The Artist's Way Workbook by Cameron Julia(2273)

The Art of Doom by Bethesda(2161)

Calligraphy For Dummies by Jim Bennett(2026)

Creative Character Design by Bryan Tillman(1927)

Botanical Line Drawing by Peggy Dean(1861)

Wall and Piece by Banksy(1827)

The Art of Creative Watercolor by Danielle Donaldson(1815)

One Drawing A Day by Veronica Lawlor(1805)

Art Of Atari by Tim Lapetino(1793)

Pillars of Eternity Guidebook by Obsidian Entertainment(1672)

Happy Hand Lettering by Jen Wagner(1599)