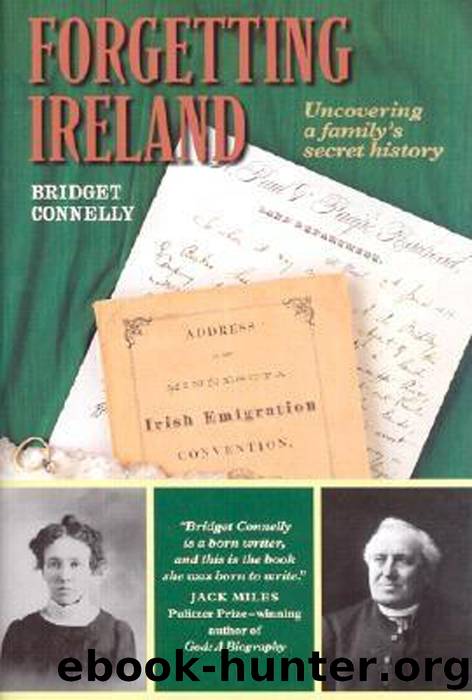

Forgetting Ireland by Bridget Connelly

Author:Bridget Connelly

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Minnesota Historical Society Press

Published: 2017-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

Part Three

RECOVERY

⢠8 â¢

Return to Connemara

âMuise, a réiteach sin ar Dhia,â a deir sÃ, âan t-athair,â a deir sÃ, âa bheith ag scaradh leis an mac an fhad is bheas uisce ag rith ná féar ag fás!â

âWell, God settle that,â says she, âthe father,â says she, âever parting with the son as long as water runs or grass grows.â

Ãamon a Búrc, Eochar, a Kingâs Son in Ireland

At the great literary gathering, the Oireáchtas, he had taken the All-Ireland Award. He had been the most exact in song and story, the wittiest in ditty, the most authoritative in lore, in all the four quarters of Irelandâ¦. After the Oireáchtas he had been detained in Dublin for a fortnight, to be lionised, to have an anthology gathered from him, to have his songs and stories put in writing so that they might be there for the Irish people to read as long as grass grows and water runs.

MáirtÃn à Cadhain, âThe Gnarled and Stony Clods of Townlandâs Tipâ

CONNEMARA! It explained everything, and more. I had to go back. My motives for returningâseveral times, it would turn outâwere partly scholarly and partly personal. The professional folklorist in me realized that my family had very recently been part of a rich oral culture and that many of the aspersions cast upon the Graceville Conamaras pointed directly to evidence of their traditional world, its values, its oral-noetic mode of preserving and transmitting culturally important informationâa world much at odds with the linear logic, the habits of mind and heart of those raised on literate discourse. As an oral traditionist, I knew that much of the conflict on the Moonshine prairie in 1880 had at its roots a clash of cultures: the literate versus the oral.

My camera-shy great-grandfather Flaherty remained very much a mystery, even though his shade accompanied me wherever my research quest led. In Minnesota, the only trace of him that surfaced was his X on citizenship papers and land transactions and, of course, the tale of the Thousand Dollar Bride. Illiterate people leave few records.

Lured by the memory of my own seanachie relative and the discovery that one of Gracevilleâs despised Conamaras had returned to Ireland to be feted as not just Irelandâs, but Europeâs, greatest bearer of oral narrative in the twentieth century, I had to return. I needed to visit again our own family bard. Would Connemara recollections of âLarry Saileâ flesh out my phantom grandfather more fully? And Ãamon a Búrc? The genuine genius seanachie who had lived so briefly near my hometownâwhat could I find of him on the coast to which he had returned? On my migration back to Connemara to recover our past, I also wanted to know more about Ireland in 1879 and 1880, more about the years the Conamaras were children and young adults during the Great Famine and the ensuing decades when they bore their own families.

The folklore researcher in me took over, and I was off to my new fieldwork site: Connemara and various Irish archives.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4289)

Never by Ken Follett(3924)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3361)

Oathbringer (The Stormlight Archive, Book 3) by Brandon Sanderson(3119)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3057)

Will by Will Smith(2894)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2345)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2316)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2297)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2210)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2185)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(2028)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1832)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1829)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1745)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1703)

515945210 by Unknown(1659)

Kingdom of Ash by Maas Sarah J(1655)

443319537 by Unknown(1540)