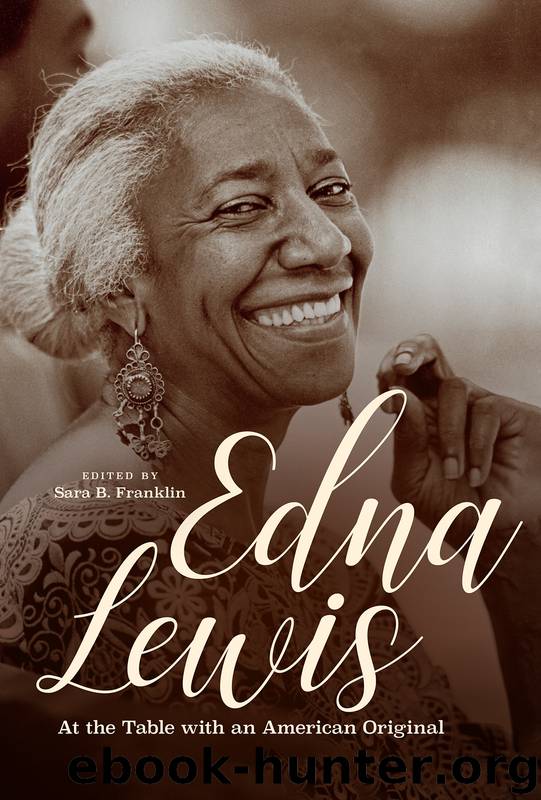

Edna Lewis by Sara B. Franklin

Author:Sara B. Franklin

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2018-05-12T04:00:00+00:00

As the colonies approached the War of Independence, tobacco’s hungry nature sucked all the nutrients out of the land and the tobacco market shrank. As a result, prices for the colony’s primary cash crop fell. Slavery in Orange shifted from King Tobacco to grains like wheat and maize in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with “the vile weed” still maintaining stubborn hooks in the economy as in other areas of the Virginia Piedmont. After emancipation, with the loss of enslaved laborers, the Virginia farming economy downsized from large tobacco and wheat plantations to orchards, livestock, and dairy.

Orange County was in the Upper South—a place with cultural and culinary connections that in some ways made it closer to the eastern midlands than those of the southern seaboard. Edna’s world was a crossroads where multiple cultures left their mark on the cuisine; the region was home for hundreds of years to the Siouan-speaking Manahoac people who were displaced by German, Welsh, English, and Scotch-Irish immigrants and forced migrants in the form of enslaved Africans. The cooking of the small farms—a European facet of the region’s heritage—is easily traced to the places from whence the settlers came, from the charcuterie and sauerkraut of Westphalia in Germany to the fruit preserves and baking traditions of Wales, Bristol and southeastern England, the surrounding counties around London, and further southwest to Kent up over to Northern Ireland. The settlers maintained contact with family and businesses in small Virginia cities like Fredericksburg and Richmond, but also with places farther afield, such as Georgetown, Annapolis, Baltimore, and even Philadelphia, thus expanding Orange County residents’ access to cookbooks, ingredients, and ideas about food in much more cosmopolitan spaces.

This is significant, given that tobacco’s depletion of the land could have easily pushed Miss Lewis’s ancestors westward to where Virginia’s enslaved often ended up once profits fell short in “Old Virginny.” Luck and circumstance, combined, allowed them to stay. The domestic slave trade was the largest forced migration in American history, moving approximately a million enslaved blacks from the Upper South states to the Lower South as tobacco land became infertile. Shifting crop cultivation obviated the need for a large year-round workforce, whereas the expanding southern cotton industry demanded a huge influx of black workers. It was Virginia’s founding fathers themselves who brokered the deal cutting off legal importations of Africans from abroad in the first decade of the nineteenth century, thus ensuring the Commonwealth a new cash crop to sell that surpassed the value of Orinoco and sweet-scented tobacco—the black body and its labor.

Edna’s great-great grandparents were probably born in the late eighteenth century. Before them, her ancestors were most likely a mixture of new African immigrants and those who had been born in Virginia. The African Virginian population was perhaps the most important demographic in the colonial and antebellum South. Although 40 percent of all enslaved Africans brought to North America entered through the port of Charleston, Virginia was responsible for the importation of almost 100,000 enslaved Africans, and most of them survived.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Biscuits: A Savor the South Cookbook by Belinda Ellis(4326)

The French Women Don't Get Fat Cookbook by Mireille Guiliano(3649)

A Jewish Baker's Pastry Secrets: Recipes from a New York Baking Legend for Strudel, Stollen, Danishes, Puff Pastry, and More by George Greenstein(3585)

Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook by Better Homes & Gardens(3575)

Ottolenghi Simple by Yotam Ottolenghi(3573)

Al Roker's Hassle-Free Holiday Cookbook by Al Roker(3519)

Trullo by Tim Siadatan(3420)

Bake with Anna Olson by Anna Olson(3391)

Hot Thai Kitchen by Pailin Chongchitnant(3367)

Panini by Carlo Middione(3323)

Nigella Bites (Nigella Collection) by Nigella Lawson(3215)

Momofuku by David Chang(3181)

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking by Nosrat Samin(3135)

Modern French Pastry: Innovative Techniques, Tools and Design by Cheryl Wakerhauser(3121)

Classic by Mary Berry(3005)

Best of Jane Grigson by Jane Grigson(2984)

Tapas Revolution by Omar Allibhoy(2973)

Solo Food by Janneke Vreugdenhil(2962)

Ottolenghi - The Cookbook by Yotam Ottolenghi(2923)