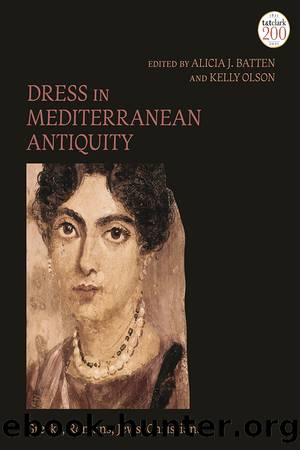

Dress in Mediterranean Antiquity by Alicia J. Batten;Kelly Olson;

Author:Alicia J. Batten;Kelly Olson;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Andromeda Unbound: Possession, Perception and Adornment in the House of the Dioscuri

NEVILLE MCFERRIN

INTRODUCTION

Dress constitutes.1 Serving both to underscore social identities and to generate them, dress is a means of self-generation as much as it is a tool of self-presentation. In such a formulation, hair coverings and tunics, perfumes and bracelets coalesce into a mutually reinforcing system, one that is experienced simultaneously by the wearer and those people with whom that wearer interacts. The audience for adornment is as variable as the medium itself, engaging the eyes of viewers and the wearerâs skin at the same moment. Even as the sheen of metal and of stone draws the eye of the viewer, their weight and rigidity serve as a haptic interface for the wearer.2 Such zones of multi-sensory interaction accentuate the tensions between the public and private valences of dress, highlighting its ability to signal an individualâs presence to others even as it underscores agency for the individual, simultaneously demarcating the boundaries of the body and offering the opportunity to engage with the environment beyond it.

By focusing upon the embodied potentials of dress, it is possible to consider an individualâs relationship to the suite of social constructions that jewellery, hairstyles, cosmetics, comportment and clothing help them to negotiate. For social actors who move through their worlds without full recourse to its resources, who are prevented by law and by custom from engaging with other actors as equals, dress offers the opportunity to aspire towards inclusion. Its visibility and manipulability insert its wearers into spaces that might otherwise exclude them. This connective potential resonates from experienced reality into depiction. In the complex communicative environment of the Pompeian house, visitors are immersed into a multi-valenced interactive space, one in which depicted and living bodies are juxtaposed with dress, both depicted and worn, eliding the boundaries between them. This is especially evident when considering jewellery depicted in figural Pompeian paintings. While wearers might be constrained by finances or social norms that restrict the types of adornment they might adopt, painters do not have to operate under such constraints. Pompeian painters could have elected to depict jewels and styles more colourful and more elaborate than those they encountered; depictions of sea monsters and putti, of women transforming into trees and of men standing aside beheaded minotaurs attest to the fact that these artists need not paint from experience. Yet, the majority of depicted adornments in the paintings of Pompeii correspond to extant examples excavated in the region of the Bay of Naples.3 As dressed figures, particularly dressed women, moved through atria and exedrae, they gazed upon figures whose dress may have looked very much like their own, perhaps inviting them to consider connections between their own realities and those depicted around them. Adornment enabled painted walls and adorned bodies to act as a reciprocal system, one that permitted visitors to these spaces to envision themselves in alternate guises, underscoring the ability of adornments to emphasize agency. If agency is the ability to highlight one of a number of intersectional identities, then adornments communicate such activations.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Magic and Divination in Early Islam by Emilie Savage-Smith;(1197)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1090)

Operation Vengeance: The Astonishing Aerial Ambush That Changed World War II by Dan Hampton(988)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(876)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(850)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(847)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(815)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(805)

Papillon by Henry Charrière(799)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(783)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(782)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(772)

Freemasons for Dummies by Hodapp Christopher;(750)

The Churchill Complex by Ian Buruma(732)

Napolean Hill Collection by Napoleon Hill(706)

The Enlightenment by Ritchie Robertson(693)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair by Bohemians Bootleggers Flappers & Swells- The Best of Early Vanity Fair (epub)(692)

Henry III by David Carpenter;(690)

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self by Unknown(666)