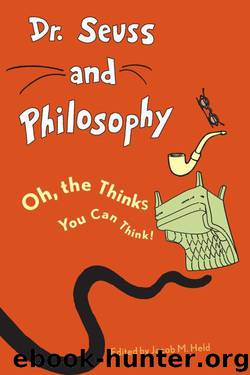

Dr. Seuss and Philosophy by Held Jacob M.; Held Jacob; Rider Benjamin; Pierlott Matthew F.; Auxier Randall E.; Novy Ron; Jeffcoat Tanya; Wilson Eric N.; Knowalski Dean A.; Alexander Thomas M.; Cunningham Anthony; Skoble Aeon J.; Cribbs Henry; Klaassen Johann A.; Klaassen Mari-Gretta G.; DwayneTunstall

Author:Held, Jacob M.; Held, Jacob; Rider, Benjamin; Pierlott, Matthew F.; Auxier, Randall E.; Novy, Ron; Jeffcoat, Tanya; Wilson, Eric N.; Knowalski, Dean A.; Alexander, Thomas M.; Cunningham, Anthony; Skoble, Aeon J.; Cribbs, Henry; Klaassen, Johann A.; Klaassen, Mari-Gretta G.; , DwayneTunstall [Held, Jacob M.; Held, Jacob; Rider, Benjamin; Pierlott, Matthew F.; Auxier, Randall E.; Novy, Ron; Jeffcoat, Tanya; Wilson, Eric N.; Knowalski, Dean A.; Alexander, Thomas M.; Cunningham, Anthony; Skoble, Aeon J.; Cribbs, Henry; Klaassen, Johann A.; Klaassen, Mari-Gretta G.; , DwayneTunstall]

Language: ru

Format: mobi

ISBN: 9781442203112

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Published: 2011-07-16T04:00:00+00:00

An Elephant Is Faithful . . . One-Hundred Percent [?]

Dr. Seuss thus clearly sides with Kant on the importance of promise keeping and honesty generally. Kant, in fact, believes that you should always be honest—that is, faithful to your word—regardless of any seemingly negative consequences. Moreover, Kant believes our moral obligations hold without exception, making him a moral absolutist. Because we have a moral duty to tell the truth (as the opposing maxim fails the universalization test), it follows that there are no circumstances in which we may permissibly break our word or practice dishonesty. This remains so even if our proposed dishonesty has no other goal than protecting innocent persons. In “On a Supposed Right to Lie from Altruistic Motives,” Kant writes, “To be truthful (honest) in all deliberation, therefore, is a sacred and absolute commanding decree of reason, limited by no expediency.”5 The idea seems to be that just as there are no exceptions to the principle that the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is 180 degrees, there are no exceptions to the principle that making lying promises is always wrong. Both are grounded in rational or logical considerations, and principles so grounded hold without exception.

But many scholars find moral absolutism to be implausible. Kant was not unaware of such concerns. To bolster his position, he considers a dilemma involving a murderer looking for his next victim. Assume that a known murderer approaches you and inquires about the location of his next intended victim, an innocent neighbor of yours. Only moments ago, you saw your neighbor frantically enter the front door of his home. What should you do? Assuming no viable third alternative, should you lie to the murderer to protect the life of your innocent neighbor or report your neighbor’s location truthfully, knowing that this will undoubtedly get the innocent man killed? Kant was clear: morally speaking, you must answer the murderer truthfully, thereby disclosing the neighbor’s location. Your duty to tell the truth is absolute.6

The debate emerging here is not whether it’s ever permissible to lie for selfish or personal gain. Should Horton break his word to Mayzie simply to avoid the ribbing of his jungle friends, he acts impermissibly. Rather, worries about the moral absoluteness of honesty are grounded in situations when moral duties conflict. We have a duty to tell the truth and a duty to protect the lives of innocent people (insofar as we can), and in this Kant agrees. However, what should we do in situations where we must choose one over the other? All systems committed to moral absolutism, Kant’s included, are conceptually precarious because they seem ill equipped to reconcile such moral dilemmas. After all, imagine the following alteration to the lying murderer case. Assume that you had promised the neighbor that you would not disclose his location to anyone, but especially the sociopath chasing him. When the murderer inquires about your neighbor’s location, what should you do? Keep your promise to your neighbor or answer the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8981)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8369)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7330)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7111)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6785)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6601)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5762)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5760)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5505)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5182)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4436)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4299)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4261)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4247)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4243)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4240)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4125)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3993)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3953)