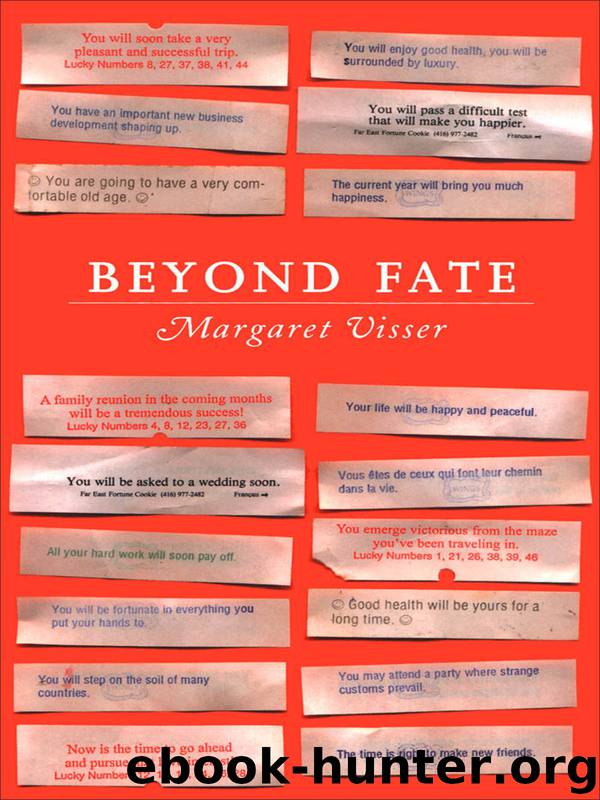

Beyond Fate by Margaret Visser

Author:Margaret Visser

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: PHI000000

Publisher: House of Anansi Press Inc.

Published: 2002-10-22T16:00:00+00:00

IV

TRANSGRESSION

THE NEED OF EVERY HUMAN BEING both for freedom and for justice is absolute and unconditional. This is one fact that all of us understand, even those who believe that nature is all there is. But nature knows nothing of freedom. It is blind and implacable; justice is nowhere to be found in it. Yet every one of us knows what freedom and justice are — most especially when we are deprived of them.

I have chosen in this book to look at metaphors for fate and their consequences. Fate is the opposite of freedom and has nothing to do with justice. Many of its metaphors derive from the universal propensity of human beings to imagine time as having spatial extension: a lifetime as a line or as a bounded area, a choice as an arrival at a crossroads, chance as the accidental intersections of lines or the collision of dots. I’ve chosen to call often on Greek (and that means also Roman) thinking about fate.

People still study the Classics in our universities largely because of the lucidity and the vividness of Greek art and thought; the contribution of the Romans (whose intellectual mentors were the Greeks) included political lessons to be derived from imperial force, practicality, and efficiency. The Greeks and Romans are like us in that historically they are our roots and their achievements are constitutive of a great deal of our culture. They are also utterly foreign to us and therefore always thoughtprovoking. For we are unlike them in important respects — in some of the most important respects of all. The familiar and the strange, the brilliantly creative, the beautiful, and the utterly weird: the combination is endlessly stimulating.

What transformed the Classical world was, of course, Christianity. The new religion was born out of the profound and revolutionary insights of Judaism — its understanding that the transcendent God is one (not a company of divinities) and also good; its view of God as alive and dynamic in the world’s history; its insistence on hope for the future. Christianity did not sweep the Classics away but carried them with it in its movement forward. In important respects, it turned Greek and Roman culture on its head, sometimes reversing rather than destroying its constructions.1

It is not my purpose in this book to explain what Christianity is. But a few examples, chosen for their relevance to my subject, may remind us of how Christianity changed our inheritance — which perdures — of the Classics. The ideals, of course, are the most important aspects of what changed. These ideals have been and still are often betrayed. But still, ideals, attitudes, and goals are as constitutive of history as are facts, misapplications, and failures. Here, then, are some examples.

Christianity, as we have already seen, substitutes guilt and forgiveness (not guilt alone) for honour and shame. It replaces time as cyclic and eternal recurrence (time as fate) with emergent possibility: change, discovery, hope, and liberation — the Jewish vision of Exodus. Its transcendent principles underwrite the equality of all human beings under God.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7550)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(6944)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(6190)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(5893)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5876)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(5795)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(4789)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(4751)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(4617)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4573)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(3730)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(3500)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3459)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(3401)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(3382)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(3272)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3263)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3233)

12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos by Jordan B. Peterson(3199)