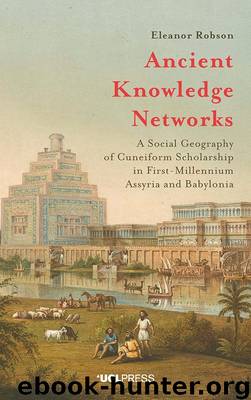

Ancient Knowledge Networks by Eleanor Robson;

Author:Eleanor Robson; [Неизв.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Book Network Int'l Limited trading as NBN International (NBNi)

Published: 2019-07-15T20:00:00+00:00

Figure 5.5: The so-called Antiochus Cylinder is the latest surviving cuneiform inscription written on behalf of a king of Babylon. It was designed in the traditional barrel-shaped format of a foundation inscription. In 268 bc it was buried in the foundations of the Ezida temple in Borsippa (under the threshold of the doorway between Court A and Room A1: Fig 5.4) during the building works it commemorates (Stevens 2014). BM ME 36277, reproduced with the permission of the British Museum.

Yet Antiochus’ relationship with the native inhabitants was not entirely supportive. A close reading of the Antiochus Cylinder shows that he was not actually present in Babylonia for the temple building works but merely ceremonially moulded bricks for it ‘in the land of Hatti’ (northern Syria).124 He relocated the Greek community in Babylon to Seleucia, more or less leaving Babylon to its own devices, while regularly imposing heavy taxes on it to pay for the new Greek city.125 Berossus (Babylonian Bel-reʾušunu or Bel-reʾušu), a self-styled contemporary of Alexander and ‘priest of Belus’ (Marduk) in Babylon,126 supposedly dedicated his Greek-language historical work Babyloniaca to Antiochus. But this testimony is given only by the early Christian theologian Tatian, writing in the second century ad – that is, some 400 years later – and so, as Geert de Breucker points out, ‘there is no reason to suppose that he [i.e. Berossus] was a member of the Seleucid court’.127

Evidence for Antiochus’ successors’ involvement in Babylonian intellectual culture is even more sparse; their attention was almost always elsewhere. There were some highlights, however: in 236 bc the šatammu and kiništu-assembly of Esangila recorded that Antiochus II (r. 261–246) had granted tax-exempted royal land ‘for the upkeep of Esangila, Ezida and Emeslam’, with the right of disposition, in perpetuity; now the temple planned to commission a stone stele recording that fact, perhaps concerned that this donation might otherwise be forgotten or rescinded.128 It may even have been this gift that enabled the šatammu and kalûs of Esangila to continue to make sacrifices to the life of the king in absentia until at least the early first century bc.129 As Lucinda Dirven notes, on the rare occasions that the Seleucid kings and officials made offerings themselves, ‘these offerings were not always undertaken out of generosity’: the Chronicles and Diaries show that they were often followed in short order by removal of, or greater control over, the temple’s dwindling assets.130

Exceptionally, Antiochus III the Great (r. 222–187 bc) participated in the akītu-festival in 205 bc to celebrate a major military victory – the first time that a king had done so, according to the surviving evidence, in around three centuries.131 Those who had last performed it in full had died out generations ago; but Babylonian scholars had presciently kept detailed instructions for just this eventuality.132 He also returned to Babylon for at least a fortnight during the last year of his reign.133 He or his grandson Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175–164 bc) formally reintroduced a Greek population into Babylon but

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Magic and Divination in Early Islam by Emilie Savage-Smith;(1197)

Ambition and Desire: The Dangerous Life of Josephine Bonaparte by Kate Williams(1087)

Operation Vengeance: The Astonishing Aerial Ambush That Changed World War II by Dan Hampton(986)

What Really Happened: The Death of Hitler by Robert J. Hutchinson(871)

London in the Twentieth Century by Jerry White(848)

Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger(844)

Twilight of the Gods by Ian W. Toll(813)

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(803)

Papillon by Henry Charrière(796)

Lenin: A Biography by Robert Service(780)

The Devil You Know by Charles M. Blow(779)

Twelve Caesars by Mary Beard(769)

Freemasons for Dummies by Hodapp Christopher;(749)

The Churchill Complex by Ian Buruma(732)

Napolean Hill Collection by Napoleon Hill(706)

The Enlightenment by Ritchie Robertson(693)

Henry III by David Carpenter;(690)

Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers, and Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair by Bohemians Bootleggers Flappers & Swells- The Best of Early Vanity Fair (epub)(688)

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self by Unknown(659)