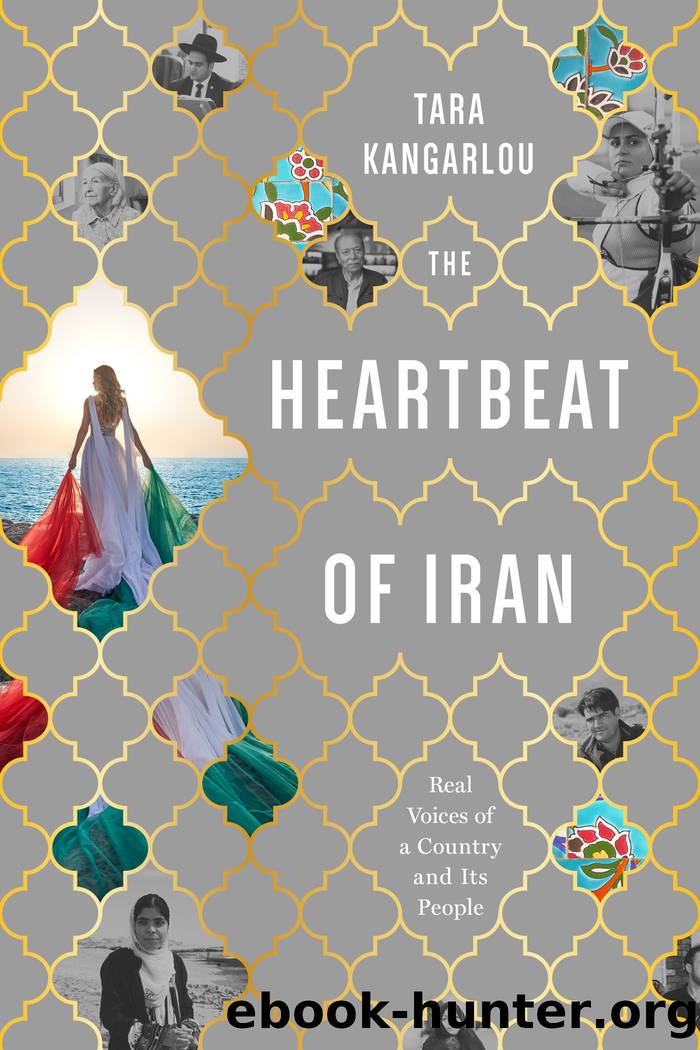

The Heartbeat of Iran: Real Voices of a Country and Its People by Tara Kangarlou

Author:Tara Kangarlou [Kangarlou, Tara]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781632462053

Google: c3-uzQEACAAJ

Publisher: Ig Publishing, Incorporated

Published: 2021-06-15T23:37:46.286530+00:00

Today, the award-winning pianist and composer lives in a small village on the outskirts of Shiraz, one of the oldest cities in Iran, which dates to the Achaemenid Empire (550â330 BC). Little is known about Persian music during that ancient era. The development of what is considered modern Persian music occurred during the Sassanid era (226â642 AD). Of particular importance during that period was Barbad, a minstrel-poet in the court of Khosrow II, the last king of the Sassanian Empire. Barbad developed the khosravani, believed to be the oldest system of modal music in the Middle East, and one that is still used by contemporary musicians in Iran. Nearly 200 years later, during the Samanid Empire, lived Rudaki, who is regarded as the first Iranian lyricist. Of his nearly 100,000 couplets, only about 1000 have survivedâthese are regarded as the blueprint for modern Persian poetry.

The diversity of classical Persian music is revealed in the mélange of the countryâs ethnicities, cultures, and tribal traditions. Persian poetry, especially that of luminaries such as Gorgani, Nizami, Rumi, Saadi, Ferdowsi, Khayam, and of course Hafez, remain the backbone of the Persian ballads and epics that were recited by musicians of their era and beyond. Of some of the greatest Persian instruments that have weathered the test of time, the Setar, Tar, and Oud may be among those most recognized by the Western world. But other classical instruments such as the Ghanun, Nay (the vertical reed flute), Robab, Tanbur, Santoor, Kamancheh, Dayereh, Dutar, and Tombak are among the centuriesâ old musical instruments that create the unique tapestry of classical Persian music.

In the sixteenth century, the Safavid Empire took power and proclaimed Shia Islam as the official religion of the country. As a result, the religionâs mournful requiems crept into the musical landscape of the country, which are still visible today in the yearly Ashura and Tasua ceremonies. The Safavid dynasty also began a wave of musical exchange with Europe that grew under the succeeding Qajar dynasty, introducing Western instruments and musical disciplines to Iran.

The popularity of classical Iranian music dwindled among the nationâs masses as European and American influence grew in the mid-twentieth century. The country then entered a musical dark age in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution, as the new regime deemed music to be haram (forbidden), and began promoting a narrative that associated music, dancing, and any sort of joyous celebration with âpaganism,â and against âIslamicâ values. Western music was regarded as a divisive tool used by the United States and its allies to tempt Muslims and promote sinful behavior. In the blink of an eye, foreign and prerevolution music were banned, women could no longer sing in public, and instruments like the violin and piano were considered âanti-revolutionary.â The country essentially went musically muteâexcept for Islamic music that was approved by the newly established government and its Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

In the years following the revolution, musicians found different ways to dodge the censorship of the regime. Some left

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4295)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

Oathbringer (The Stormlight Archive, Book 3) by Brandon Sanderson(3160)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3072)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2324)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2197)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(2042)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1842)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1840)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1754)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1722)

Kingdom of Ash by Maas Sarah J(1668)

515945210 by Unknown(1662)

443319537 by Unknown(1546)