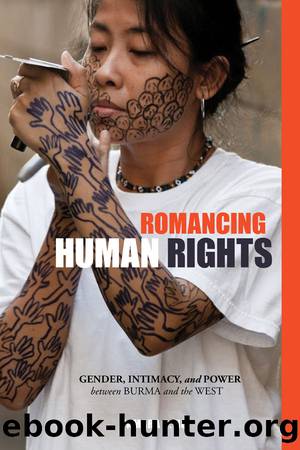

Romancing Human Rights: Gender, Intimacy, and Power between Burma and the West (Intersections: Asian and Pacific American Transcultural Studies) by Tamara Ho

Author:Tamara Ho [Ho, Tamara]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: University of Hawaii Press

Published: 2015-08-03T16:00:00+00:00

I see myself sometimes quite differently from how other people see meâ¦. when people say, âHow marvelous it is that you stuck out those six years of detention,â my reaction is, âWell, whatâs so difficult about it? Whatâs all the fuss about?â Anybody can stick out six years of house arrest. Itâs those people who have had to stick out years and years in prison, in terrible conditions, that makes you wonder how they did it. So, I donât see myself as all that extraordinary. I do see myself as a trier. I donât give upâ¦. [B]ut basically I donât give up trying to be a better person.117

Aung San Suu Kyiâs distinctive modesty and determination shine through, in contrast to her overdetermined image as the symbol of Burma. She denounces heroic status and cults of personality and makes plain the privileges she has over other Burmese political prisoners, in terms of the relatively tolerable conditions of her house arrest. Quoting âone of the drafters of the Constitution of India,â she asserted that âhero worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorshipâ and told people in her own words that âthere is no room for hero-worship in a true political struggle made up of human beings grappling with human problems.â118 Although Aung San Suu Kyi has followed her fatherâs model, âsharpening herself into an incorruptible leader for the cause of democracyâcapable of sacrificing her own life,â she ultimately returns to the importance of a diverse set of peoples working together as a whole and the shared humanity and potential agency of everyone who wishes to see a better Burma, be they Burmese or not.119 By categorizing herself as simply a person who tries, she becomes a role model accessible to the people of Burma and around the world.

Despite fifteen years of detention, Aung San Suu Kyi remained stubbornly committed to her vision of political change and reconciliation. She remained cautiously optimistic and politic about finding terms of agreement with her former captors and the military ruling party. During her years of house arrest and famous 1998 protest (in which she stopped her car on the bridge and refused to move), Aung San Suu Kyi proved to be a woman with an indomitable sense of moral justice who has, as one friend noted, not only the courage of her convictions, but also the courage to utilize her connections.120 By tactically deploying transcultural knowledge in a multivalent fashion, Aung San Suu Kyi displaces binary divisions of gender, culture, and liberation and advocates a flexible mode of nonviolent change and synthesis. She explains, âI never say Iâm going to do this or that. Thatâs something Iâve never done, because in politics, one has to be flexible.â121 Akin to Gloria Anzaldúaâs la mestiza (see Borderlands: The New Mestiza/La Frontera), Aung San Suu Kyi negotiates languages, straddles multiple cultures, and articulates spiritual and political identities to articulate a border-crossing paradigm of resistance and change. Situating knowledge and bringing it to a specific level of application can have a profound effect on peopleâs lives.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4295)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

Oathbringer (The Stormlight Archive, Book 3) by Brandon Sanderson(3160)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3072)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2324)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2197)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(2042)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1842)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1840)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1754)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1722)

Kingdom of Ash by Maas Sarah J(1668)

515945210 by Unknown(1662)

443319537 by Unknown(1546)