Lodgers, Landlords, and Landladies in Georgian London by Gillian Williamson

Author:Gillian Williamson [Williamson, Gillian]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, General, Europe, Great Britain, Social History, Modern, Georgian Era (1714-1837)

ISBN: 9781350253599

Google: 1vw0EAAAQBAJ

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Published: 2021-07-15T01:13:32+00:00

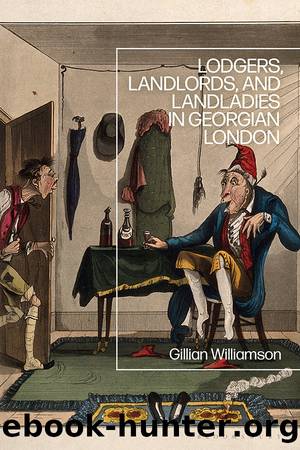

Figure 15 Henry Heath, Comfortable Lodgings, 1829. Landlords/ladies of houses with multiple lodgers had to balance competing lifestyles. Here it is past three oâclock in the morning and on the ground floor a bachelor party, like that held by James Boswell at the Terriesâ, is in full swing. The first-floor lodger, his wife in the background, and a fellow-lodger in the front garret complain of the lack of sleep. Note the domestic touch of pot-plants on the garret window-sill. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University: 829.00.00.51+.

For landlords and ladies and their families the possibility of being overheard was worse. It represented a considerable diminution of the privacy that was essential to the domestic ideal. Boswell, Cruden, and Cannon all complained of overhearing quarrels within the host family and with other members of the household. Some lodgers actually meddled in family affairs. Boswell told Mrs Terrie that she should make her husband âgive over letting lodgings, as he was very unfit for itâ.148 Curwen doled out advice to the Poyntons when their daughter ran off abandoning her husband and child, offering to intervene with the mother-in-law.149 At his Gloucester Street lodgings in Bloomsbury in 1769, Neville (Sally being absent in Eastbourne) insinuated himself as confidant to landlady Mrs Willoughby, learned that she was unhappy in her marriage, and then used the knowledge to indulge in a dalliance with her under Mr Willoughbyâs nose.150 This gross breach of trust, reminiscent of Chaucerâs Millerâs Tale, is examined further in Chapter 6.

Meals were a further source of discontent. As with rising and retiring to bed, timing was an issue. Mealtimes and menus were, naturally, set by the landlord/lady. In 1776 Curwenâs 13s. weekly rent at the Heraldâs Office included, inter alia, breakfast and dinner. After only two weeks he was âfinding an inconvenience in conforming to the family hour, being unfavourably earlyâ. He and the landlady agreed that he would now find his own breakfast and dine âabroadâ. This alteration in their terms suited Curwen rather than the landlady who lost a little income and any company for which she had hoped. Then there was the quality and quantity of the food provided. Landlords/ladies had to be careful not to blow their household budgets by being over-generous with the portions. Emin agreed 1s. a day for lodging, washing and board with Mrs Newman in 1751. After fifty days she had to take him aside and let him know that he was eating too much at this price. He then offered a guinea a month on top of rent, washing and shaving.151 Sometimes a lodger struck lucky. Curwenâs Mrs Longbottom provided âa table an Epicure wouldnât or couldnât reasonably condemn, she being an excellent cookâ.152 However many lodgers, Curwen included, felt that in their eagerness to extract profit, landlords/ladies were inclined to cut corners. Goldsmith said of his landladyâs regime in Edinburgh, where in 1752 he was studying medicine, that a leg of mutton âserved for the better part of dinner during the weekâ, ending as bone broth on the seventh day.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4295)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

Oathbringer (The Stormlight Archive, Book 3) by Brandon Sanderson(3157)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3072)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2324)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2197)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(2041)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1842)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1840)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1754)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1722)

Kingdom of Ash by Maas Sarah J(1668)

515945210 by Unknown(1660)

443319537 by Unknown(1545)