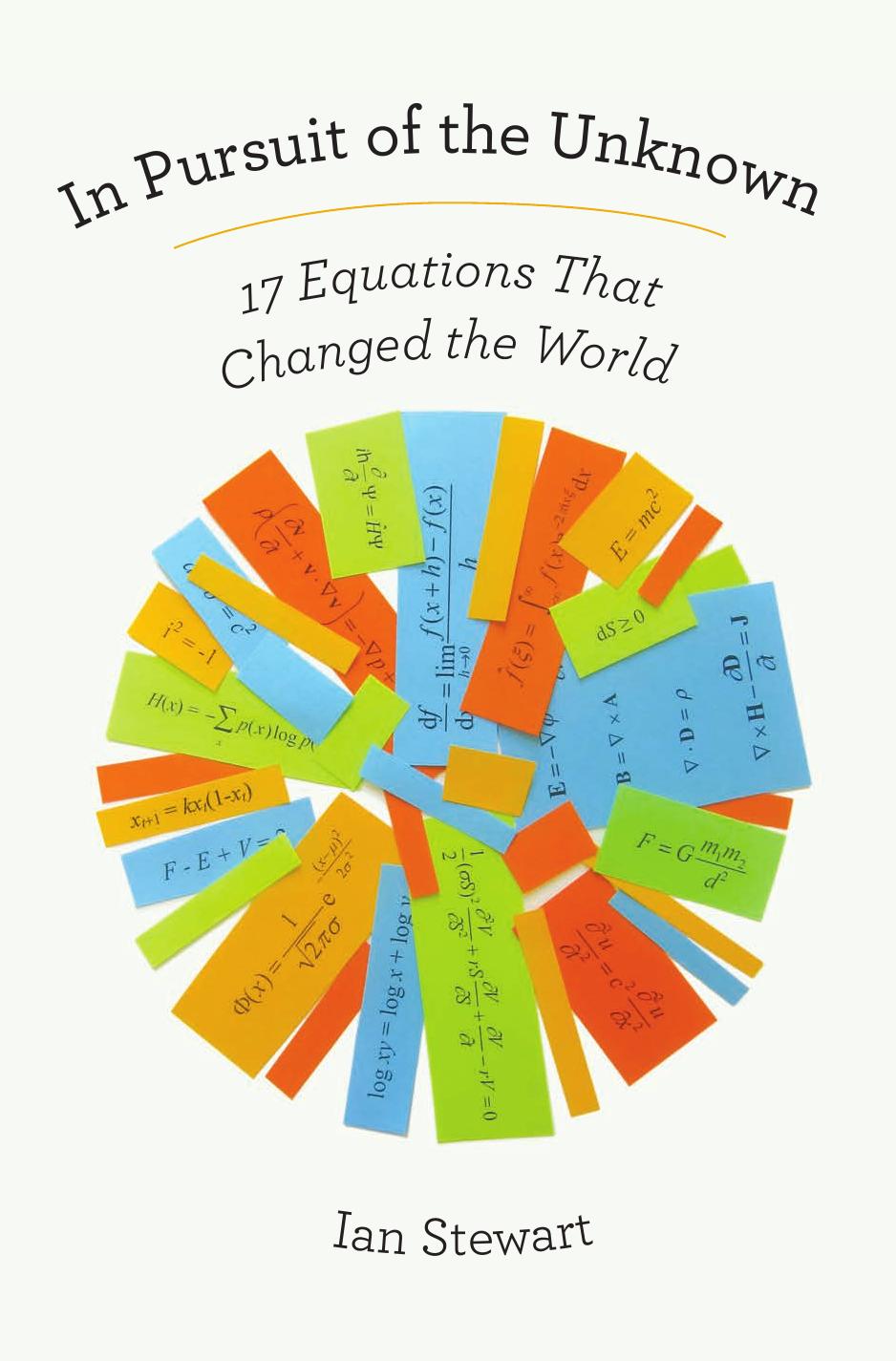

In Pursuit of the Unknown: 17 Equations That Changed the World by Ian Stewart

Author:Ian Stewart [Stewart, Ian]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: Mathematics, History & Philosophy

ISBN: 9780465029747

Publisher: Basic Books

Published: 2012-03-13T00:00:00+00:00

The Navier–Stokes equation has another application: climate change, otherwise known as global warming. Climate and weather are related, but different. Weather is what happens at a given place, at a given time. It may be raining in London, snowing in New York, or baking in the Sahara. Weather is notoriously unpredictable, and there are good mathematical reasons for this: see Chapter 16 on chaos. However, much of the unpredictability concerns small-scale changes, both in space and time: the fine details. If the TV weatherman predicts showers in your town tomorrow afternoon and they happen six hours later and 20 kilometres away, he thinks he did a good job and you are wildly unimpressed. Climate is the long-term ‘texture’ of weather – how rainfall and temperature behave when averaged over long periods, perhaps decades. Because climate averages out these discrepancies, it is paradoxically easier to predict. The difficulties are still considerable, and much of the scientific literature investigates possible sources of error, trying to improve the models.

Climate change is a politically contentious issue, despite a very strong scientific consensus that human activity over the past century or so has caused the average temperature of the Earth to rise. The increase to date sounds small, about 0.75 degrees Celsius during the twentieth century, but the climate is very sensitive to temperature changes on a global scale. They tend to make the weather more extreme, with droughts and floods becoming more common.

‘Global warming’ does not imply that the temperature everywhere is changing by the same tiny amount. On the contrary, there are large fluctuations from place to place and from time to time. In 2010 Britain experienced its coldest winter for 31 years, prompting the Daily Express to print the headline ‘and still they claim it’s global warming’. As it happens, 2010 tied with 2005 as the hottest year on record, across the globe.1 So ‘they’ were right. In fact, the cold snap was caused by the jet stream changing position, pushing cold air south from the Arctic, and this happened because the Arctic was unusually warm. Two weeks of frost in central London does not disprove global warming. Oddly, the same newspaper reported that Easter Sunday 2011 was the hottest on record, but made no connection to global warming. On that occasion they correctly distinguished weather from climate. I’m fascinated by the selective approach.

Similarly, ‘climate change’ does not simply mean that the climate is changing. It has done that without human assistance repeatedly, mainly on long timescales, thanks to volcanic ash and gases, long-term variations in the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, even India colliding with Asia to create the Himalayas. In the context currently under debate, ‘climate change’ is short for ‘anthropogenic climate change’ – changes in global climate caused by human activity. The main causes are the production of two gases: carbon dioxide and methane. There are greenhouse gases: they trap incoming radiation (heat) from the Sun. Basic physics implies that the more of these gases the atmosphere contains, the more heat it traps; although the planet does radiate some heat away, on balance it will get warmer.

Download

In Pursuit of the Unknown: 17 Equations That Changed the World by Ian Stewart.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6432)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6264)

Factfulness: Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling(4731)

A Mind For Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra) by Barbara Oakley(3301)

Descartes' Error by Antonio Damasio(3270)

Factfulness_Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World_and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling(3230)

TCP IP by Todd Lammle(3180)

Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(3105)

The Tyranny of Metrics by Jerry Z. Muller(3065)

Applied Predictive Modeling by Max Kuhn & Kjell Johnson(3064)

The Book of Numbers by Peter Bentley(2964)

The Great Unknown by Marcus du Sautoy(2690)

Once Upon an Algorithm by Martin Erwig(2641)

Easy Algebra Step-by-Step by Sandra Luna McCune(2628)

Lady Luck by Kristen Ashley(2576)

Police Exams Prep 2018-2019 by Kaplan Test Prep(2540)

Practical Guide To Principal Component Methods in R (Multivariate Analysis Book 2) by Alboukadel Kassambara(2538)

All Things Reconsidered by Bill Thompson III(2389)

Linear Time-Invariant Systems, Behaviors and Modules by Ulrich Oberst & Martin Scheicher & Ingrid Scheicher(2364)