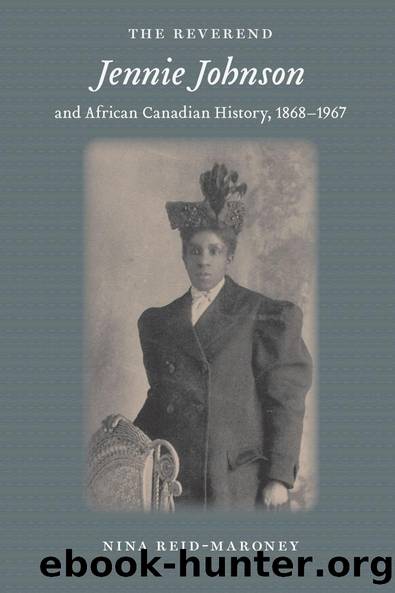

The Reverend Jennie Johnson and African Canadian History, 1868-1967 by Nina Reid-Maroney

Author:Nina Reid-Maroney [Reid-Maroney, Nina]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781580464475

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Boydell & Brewer, Limited

Published: 2013-04-01T00:00:00+00:00

Figure 5.1. Jennie Johnsonâs Certificate of Ordination. Reproduced with permission from Canadian Baptist Archives (biographical file: Johnson, Jennie).

Understanding the importance Johnson attached to this event requires that we revisit the ordination question, even though this question is not a fashionable one.29 Taking full measure of the damage done, many feminist historians see patriarchal religious institutions as lying well beyond the realm of things worth saving, and perhaps beyond the realm of things worth talking about. Recent scholars of religion and womenâs spirituality tend to avoid serious studies of ordination debates, arguing that the ordination question at best leaves out the most interesting bits of womenâs religious experience, and at worst retains the centrality of patriarchy. The point is well-taken, but does not change the way in which women such as Johnson saw things for themselves. Full participation in the order of ministry had the double effect of blunting the patriarchal edge of Christianity even as it sharpened Christianityâs edge of justice.

Johnsonâs ministry uncovered afresh the central paradox of Protestantism: with respect to women it is a religious tradition that carries both the power to oppress and the power to liberate.30 Certainly the relationship between Christianity and womenâs power was a matter seriously contested by Johnsonâs contemporaries, black and white, including late nineteenth-century women who guided feminist ideas through the untested waters of biblical criticism. Elizabeth Cady Stanton made the point with characteristic clarity when she asked other activists in the womenâs movement to answer two questions: â1. Have the teachings of the Bible advanced or retarded the emancipation of women? 2. Have they dignified or degraded the Mothers of the Race.â31 Many of the responses appended to the 1898 Womanâs Bible supported Stantonâs answer; other respondents pointed to Christian principles of divine justice and to the example of Christ, arguing that Christianity could serve feminist purposes. Jennie Johnsonâs answer to the question of just when and why the balance might tip to favor the liberating possibilities of Christianity over the oppressive ones was found where white women of Johnsonâs generation seldom looked for it: in the politics of race.

She also displayed a sense of newness in her life as minister, and an intellectual flexibility, of which we can know something by the company she sought out and kept in her professional life. Her connections depended on a willingness to take seriously the course of early twentieth-century theology while remaining impassioned about telling the old, old story. Johnson officially entered the denomination in the midst of debate centered on theological education and the Michigan Associationâs support for teaching at Hillsdale College. At issue was the matter of biblical criticism, and whether or not âHillsdale College, the theological department included,â deserved continued support from the Association. It was set to rest only through the reassurances offered by Leroy Waterman, professor of Hebrew at the college, who âtook the floor and for two hours or more explained his doctrinal views and answered questions in the sweetest of spirits and with an ability that went far toward dispelling whatever doubts may have existed before.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Crazy Town by Robyn Doolittle(1576)

The Art of Leaving by Ayelet Tsabari(1520)

The Lives of Conn Smythe by Kelly McParland(1487)

Canadians by Roy MacGregor(1460)

Bugaboo Dreams by Topher Donahue(1416)

Chris Chelios by Chris Chelios(1413)

Beyond the Dance by Chan Hon Goh(1366)

Creatures of the Rock by Andrew Peacock(1356)

Good Bones by Margaret Atwood(1328)

Blood, Sweat and Fear by Eve Lazarus(1267)

Big Bear by Rudy Wiebe(1218)

I Hear She's a Real Bitch by Jen Agg(1214)

The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Philosophers in America From 1600 to the Present by Shook John R(1203)

The McDavid Effect by Marty Klinkenberg(1191)

From the Tundra to the Trenches by Eddy Weetaltuk(1184)

Houses Made of Wood and Light by Michele Dunkerley(1142)

A New Kind of Monster by Timothy Appleby(1141)

Born Naked by Farley Mowat(1135)

His Brother's Bride by Nancy M Bell(1120)