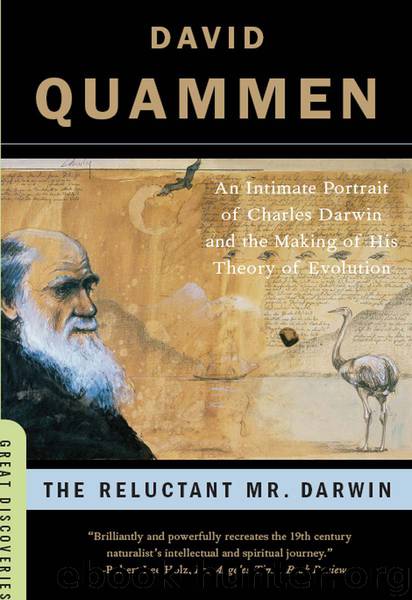

The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution (Great Discoveries) by David Quammen

Author:David Quammen

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2007-07-16T14:00:00+00:00

After a year in Sarawak, Alfred Wallace shifted onward in the Malay Archipelago to find new hunting grounds, beyond the range of previous British travelers and collectors. He caught a Chinese-owned schooner that stopped briefly at Bali and then deposited him on Lombok, a small island just thirty miles further east. Wallace stayed on Lombok for two months, shooting birds and observing the local culture while waiting for another boat that would take him to Macassar, a port on the bigger island of Celebes. Lombok is where he first encountered the sulfur-crested cockatoo, a gorgeous but noisy bird not found on Bali or any of the other islands westward. He also noticed the rainbow bee-eater, another pretty species common in Australia. Wallace would eventually realize from these signals and others that, just in bouncing from Bali to Lombok, across a narrow but deep strait, he had moved from one biogeographical zone into another. He was now in the realm of Australian fauna. That seemed odd. Why should there be such well-demarcated zones?

From Lombok, he sent off a crate of specimens, to Stevens in London by way of Singapore, containing more than three hundred bird skins. Most of those, including as many cockatoos as he’d been able to kill, were intended for sale. The crate also contained something so ordinary that, coming from a commercial collector of biological exotica, it must have seemed peculiar: a local variant of the barnyard duck. Wallace’s note to the agent explained: “The domestic duck var. is for Mr. Darwin.” Please forward.

It’s hard to say whether that duck ever reached Darwin. If so, he was presumably grateful but not surprised. He had come to expect a high degree of generous cooperation from the people (especially those below him in social status) he called on for research assistance. Around the same time, Wallace wrote to him directly. Sent from Celebes, traveling the slow mail routes of the day, this letter took six months to reach Down House. Like Darwin’s first note to Wallace, it hasn’t been preserved in the huge archive of Darwin correspondence; its existence and contents can only be inferred from the reply it evoked. “By your letter, & even still more by your paper in Annals,” Darwin wrote Wallace on May 1, 1857, “I can plainly see that we have thought much alike.” Choosing his phrases with some delicacy, he added that “to a certain extent” they had reached “similar conclusions.” Furthermore, Darwin said, he endorsed “almost every word” of Wallace’s paper and considered it rare for two theorists to agree so closely. Given Darwin’s cold dismissal of the “law” paper in his reading notes—“nothing very new”—this was spreading the butter a bit thickly.

But something had changed. Wallace’s lost letter may have contained a declaration of transmutationist views, and maybe also a boast that his paper was just the first step toward an explanatory theory. Such news would have put Darwin on guard. In any case Darwin knew that Wallace, consciously or not, was noodling along the edges of transmutationism.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14370)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5366)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4909)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3765)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3687)

Brief Answers to the Big Questions by Stephen Hawking(3430)

Inferior by Angela Saini(3311)

Origin Story by David Christian(3195)

Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design by Stephen C. Meyer(3132)

The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee(3095)

The Evolution of Beauty by Richard O. Prum(2993)

Aliens by Jim Al-Khalili(2827)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2813)

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bryson Bill(2689)

Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality by Ryan Christopher(2528)

From Bacteria to Bach and Back by Daniel C. Dennett(2483)

Endless Forms Most Beautiful by Sean B. Carroll(2478)

Who We Are and How We Got Here by David Reich(2431)