Reconstruction's Ragged Edge by Steven E. Nash

Author:Steven E. Nash [Nash, Steven E.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, United States, Civil War Period (1850-1877), State & Local, South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV)

ISBN: 9781469626253

Google: _8g3CwAAQBAJ

Publisher: UNC Press Books

Published: 2016-01-13T02:58:47+00:00

Chapter Six: The Beginning of a âNewâ Mountain South

Agriculture, Railroads, and Social Change, 1872â1880

Wilkes County had little to offer William Horton Bower, an ambitious and well-connected young man, in 1873. The postwar years had not been prosperous ones for western North Carolinians. Currency dried up, debts threatened familiesâ farms, and the stateâs railroads teetered on bankruptcy. Searching for opportunity, Bower sought the guidance of Augustus S. Merrimon, the Buncombe County judge who had lost the 1872 gubernatorial election only to be named a U.S. senator the following year. Merrimon endeavored to keep the young man at home, even if it made his advice somewhat disingenuous. âI doubt very much the wisdom of leaving North Carolina,â Merrimon advised. Things looked bleak, but Merrimon trusted that âwe have a soil, climate and advantages that capital and labor will take advantage ofâ once âthe misrule which has cursed and crushed us so longâ succumbed âto wise counsel and the peremptory demands of society for wholesome government.â Patience was one resource mountaineers could ill afford to exhaust. âYou are in the right section of the State, if you can afford to come on gradually & not despise small thingsâ because âthere is more for young men of talent and moral excellence in any of our Western Counties.â1

Beneath Merrimonâs optimistic advice was some âDo as I say, not as I doâ hypocrisy. Confronted with similar straits in 1867, Merrimon opted to resign his mountain judgeship in favor of a legal practice in the state capital. At that time, he viewed western North Carolina as a dead end. Six years later, one must wonder whether Senator Merrimon recognized the irony in instructing somebody not to follow in his footsteps. For all the wrangling and second-guessing, Merrimon lost the young man to the romance of the West. William Horton Bower chose California and a teaching career over waitingâand hopingâfor his native section to recover.2

Regardless of Bowerâs decision, Merrimon mapped out a vision for the future shared by many of his fellow Conservativesâincluding those in the mountains. A ânewâ South appeared on the horizon, one that capitalized on the soil, climate, and resources that Merrimon praised in his missive to Bower. Labor and capital would develop those resources, but equally important was the end of what Conservatives decried as Republican misrule. The two aims were inseparable for men like Merrimon. In order to move the state forward, to extract the natural resources of western North Carolina, to complete the long-stalled railroads, and to restore good government, the biracial Republican regime that captured the state government in 1868 had to fall. The middle-class white urban Republicans of the mountain counties did not repudiate their previous African American allies; rather, they deemphasized divisive issues such as civil rights in order to achieve long-frustrated hopes for the regionâs internal improvement. Ku Klux Klan assaults and intimidation began the process, and a market-oriented New South would finish it.3

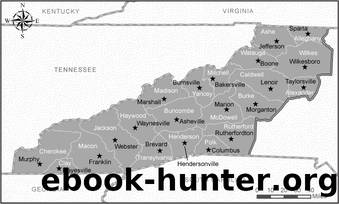

Western North Carolina lagged behind neighboring mountain regions in several important ways. Both southwest Virginia and East Tennessee had railroads and had expanded market production prior to the Civil War.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Coloring Books for Grown-Ups | Humor |

| Movies | Performing Arts |

| Pop Culture | Puzzles & Games |

| Radio | Sheet Music & Scores |

| Television | Trivia & Fun Facts |

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5165)

Paper Towns by Green John(5163)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4281)

Never by Ken Follett(3918)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3353)

Learning C# by Developing Games with Unity 2021 by Harrison Ferrone(3350)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3062)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3055)

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: Illustrated edition by J.K. Rowling & Newt Scamander(3005)

Will by Will Smith(2891)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2833)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2801)

Never Lie: An addictive psychological thriller by Freida McFadden(2545)

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them: The Original Screenplay by J. K. Rowling(2493)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2340)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2317)

Borders by unknow(2297)

The God delusion by Richard Dawkins(2293)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2208)