Dakota in Exile by Clemmons Linda M.;

Author:Clemmons, Linda M.;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses)

Published: 2019-02-24T16:00:00+00:00

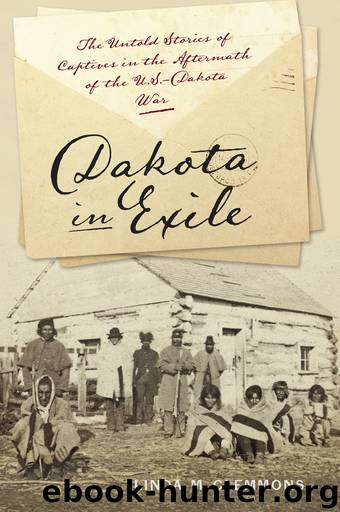

FIGURE 16. Part of General Sully’s army near Fort Berthold, North Dakota, during his summer 1864 punitive expedition. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Battles like Whitestone Hill and Killdeer Mountain brought peaceful tribes into the conflict and increased volatility on the western frontier. Stephen Riggs, who served as a military interpreter on the expeditions, stated that “the present result of our campaign is that the Ehanktonwans and Yanktonais have been engaged in the [war], as very likely the Tetonwans will be also.” Historian Paul Beck agrees, commenting that the “columns of vengeance” of 1863 and 1864 inflicted destruction “not only on the handful of resisters, but also on those who favored peace and had no part in the war.” By 1865, as historian Robert Utley argues, the punitive campaigns against Dakota had “set off a chain reaction that . . . locked Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche in a war with the whites that overspread the Great Plains from the upper Missouri to the Red River.” Indeed, in summer 1865, Major General Pope planned to move into present-day Montana and Wyoming, far beyond his original campaigns in Dakota Territory. Thus, a relatively short and isolated war in Minnesota became one—although not the only—of the precipitating events in the overall war for the western plains that did not end until the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890.

Dakota scouts participated in all the military campaigns that followed the U.S.-Dakota War. General Sibley authorized the first group of scouts in late winter 1863, after Gabriel Renville (held at Fort Snelling) recommended appointing himself and nine of his fellow prisoners as scouts. By spring, the number of scouts had increased to approximately thirty men. Members of this initial cohort had similar backgrounds. Many shared kinship ties. For example, nine of the scouts had the last name of Renville, including Gabriel (who served as head of the Dakota scouts), Joseph Akipa, Victor, Antoine, Michael, Isaac, and Daniel Renville. Others also had kin ties to the Renville family, including Red Iron, Amos Ecetukiya, Solomon Two Stars, and Lorenzo Lawrence and Joseph Kawanke (Sarah Hopkins’s brothers). Many of these scouts had been affiliated with the ABCFM in the prewar years, including Lorenzo Lawrence, Joseph Kawanke, Paul Mazakutemani, Simon Anawangmani, John Other Day, and Joseph Napayshne. Stephen Riggs noted that “more than one half—perhaps about three fifths of all our old church members are in this little band” of initial scouts. Other scouts belonged to the Episcopal Church, including Good Thunder and Wabasha. Many had long-standing affiliations with traders, including the Campbell, LaFramboise, Freniere, More, and Robertson families. Many had connections to all three of these categories: the Renvilles, Protestant missionaries, and traders. Many scouts were older: in 1863, Joseph Akipa Renville was sixty-eight; Simon Anawangmani, forty-nine; and Paul Mazakutemani, fifty-seven. Finally, according to Riggs, during the war all these scouts had “showed themselves to be on the side of the white people.”

After 1863, the number of Dakota scouts increased, especially during 1865. By 1866, when the scouting program ended, approximately 280 men had served as scouts.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

1861 by Adam Goodheart(1049)

Smithsonian Civil War by Smithsonian Institution(1009)

Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 2 by Michael Burlingame(967)

The Fiery Trial by Eric Foner(940)

Ulysses S. Grant by Michael Korda(932)

Rock of Chickamauga(926)

Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson(923)

Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson by S. C. Gwynne(916)

101 Things You Didn't Know About Lincoln by Brian Thornton(908)

Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen by Rae Katherine Eighmey(862)

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust(834)

Bloody Engagements by John R. Kelso(821)

Lincoln's Lieutenants by Stephen W. Sears(804)

Union by Colin Woodard(800)

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman(790)

The escape and suicide of John Wilkes Booth : or, The first true account of Lincoln's assassination, containing a complete confession by Booth(764)

1861: The Civil War Awakening by Adam Goodheart(747)

Rise to Greatness by David Von Drehle(728)

The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery by Eric Foner(720)