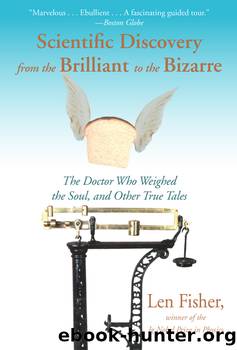

Scientific Discovery From the Brilliant to the Bizarre: The Doctor Who Weighed the Soul, and Other True Tales by Len Fisher

Author:Len Fisher [Fisher, Len]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: science, Research & Methodology, reference, Philosophy & Social Aspects, history, Medical

ISBN: 9781611459128

Google: _DeCDwAAQBAJ

Publisher: Simon and Schuster

Published: 2013-04-04T23:40:57.125520+00:00

Figure 6.3. Frogâs leg being stimulated by a pair of linked wires.

SOURCE: J. Malmivuo and R. Plonsey, Bioelectromagnetism (London: Oxford University Press, 1995). Internet version http://butler.cc.tut.fi/~malmivuo/bem/bembook/00/ti/htm.

The storm aroused by the publication of the commentaries among physicists, physiologists and physicians [could] be compared only to the storm that at the same time arose on the political horizons of Europe. It [could] be said wherever there were frogs, and wherever two dissimilar metals could be fastened together, people could convince themselves with their own eyes of the marvellous revival of severed limbs.

Volta was quite right. Dissimilar metals (or any conductors) in contact do produce their own electricity (this phenomenon, discovered by Volta, is known as the âcontact potentialâ). But Galvani was also right. Animal nerves also produce their own electricity. Unfortunately, he didnât know how they do it, and this left a hole in his argument that Volta was quick to seize upon, and which led to the invention of the battery.

Voltaâs idea was simple. If he could replace the frog in Galvaniâs experiment by something inanimate, like a piece of wet cardboard, and still produce electricity by contacting it with a pair of dissimilar metals on either side, then that would mean that living (or recently dead) matter was not necessary for the production of the electricity. He described his experiment on March 20, 1800, in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks, secretary of the Royal Society in London. The metals (silver and zinc) and the cardboard were in the form of disks, about twenty-five millimeters in diameter. Volta multiplied their effect by stacking them as high as he could manage in a pile, in the order silver, zinc, pasteboard, silver, zinc, pasteboard, silver, zinc, etc. When he touched the two ends and received a shock, he knew that his pile was producing electricity.

The experiment had a huge effect on the Italian (and world) scientific community, which up until then had been divided between Galvani and Volta in its support. Its impact was such that Galvaniâs experiments and interpretations were utterly discounted from that time on. Volta used it to argue that âanimal electricityâ was a fiction, and that even its bestknown example, that of the Torpedo (or electric ray), functioned in the same way as his battery. âNot even in this case,â he said, âis it proper to speak of animal electricity, in the sense of being produced or moved by a truly vital or organic action. . . . Rather, it is a simple physical, not physiological, phenomenon â a direct effect of the Electromotive apparatus contained in the fish.â

Volta argued that his experiments with different metals, both on their own and in the form of his âpile,â conclusively showed that âherein lies the whole secret, the whole magic of Galvanism. It is simply an artificial electricity, which acts under the impulse of different conductors.â

Voltaâs discoveries of âartificial electricityâ from the contact potential and the voltaic pile have found widespread application. Ironically, one of the less obvious applications is named after Galvani.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Administration & Medicine Economics | Allied Health Professions |

| Basic Sciences | Dentistry |

| History | Medical Informatics |

| Medicine | Nursing |

| Pharmacology | Psychology |

| Research | Veterinary Medicine |

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4110)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3195)

Will by Will Smith(2771)

Hooked: A Dark, Contemporary Romance (Never After Series) by Emily McIntire(2482)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2273)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2100)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2063)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(1935)

The Strength In Our Scars by Bianca Sparacino(1766)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1764)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1744)

Leviathan Falls (The Expanse Book 9) by James S. A. Corey(1630)

515945210 by Unknown(1584)

A Game of Thrones (The Illustrated Edition) by George R. R. Martin(1563)

Bewilderment by Richard Powers(1520)

443319537 by Unknown(1451)

The 1619 Project by Unknown(1366)

The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health (Childrenâs Health Defense) by Robert F. Kennedy(1361)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1268)