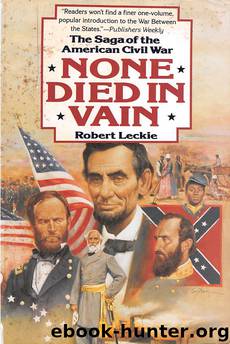

None Died in Vain by Robert Leckie

Author:Robert Leckie

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2018-12-29T16:00:00+00:00

39

Withdrawal from the Peninsula: Union Squabbles in the West

GENERAL HILL was right, but the great tragedy of the Civil War was that neither he nor General Lee nor U. S. Grant nor any other high commander ever came to realize why it was that war had become “murder,” or, in the phrase of William Tecumseh Sherman, “all hell.”

The rifle bullet was the reason. The bullet had given the advantage to the defense. It had dethroned the bayonet, the shock weapon of the assault, and together with its handmaidens, the ax and the spade, had made the defense just about invincible.

The point that had been missed was that the rifle bullet ended the era of headlong assault. In the days of edged or pointed weapons—the sword, the battle-ax and the lance—the assault was the ultimate tactic because all fighting was hand to hand. An attacker had little difficulty in approaching his enemy. This situation might have been ended by the bow and arrow, except that the invention of gunpowder came so close upon perfection of the English longbow that the possibilities of this silent missile were not fully realized. When smoothbore muskets appeared the bullet was subordinated to the bayonet.

What was needed were new weapons and tactics whereby the defense could be pinned down in its entrenchments while its flanks were turned, or so that the attack might advance to within assault range at a minimum risk. These were not developed, and it would be far from fair to fault either Lee or Grant for failing to understand the revolution worked by the rifle bullet. It was not understood in the West as late as World War I and beyond, when automatic weapons and barbed wire made the power of defense even greater, and the famous “banzai” charges of the Japanese during World War II were even bloodier repetitions of the shock tactics that reddened the slopes of Malvern Hill.

Lee’s explanation for these assaults was that he believed the enemy to be demoralized. Granting him the universal failure to grasp the limitations now imposed upon the attack, his judgment must be upheld. During the Seven Days’ Battles begun at Mechanicsville and ended at Malvern, Lee had suffered 20,000 casualties against 16,000 Union losses, and yet it was McClellan, not Lee, who was backing off.

McClellan ordered a general retreat to Harrison’s Landing on the James about fifteen miles below Richmond. His decision enraged many of his officers, none more than Phil Kearny, who slammed his famous kepi into the mud, and roared: “I, Philip Kearny, an old soldier, protest this order for retreat. We ought, instead of retreating, to follow up the enemy and take Richmond. And in full view of all the responsibility of such a declaration, I say to you all, such an order can only be prompted by cowardice or treason.”

Neither accusation, of course, was true. Phil Kearny was one of those fighting generals who walk in a two-tone world and whose contempt for politics often conceals an inability or reluctance to swim in those conflicting currents.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

1861 by Adam Goodheart(1049)

Smithsonian Civil War by Smithsonian Institution(1009)

Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 2 by Michael Burlingame(968)

The Fiery Trial by Eric Foner(940)

Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson(935)

Ulysses S. Grant by Michael Korda(933)

Rock of Chickamauga(926)

Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson by S. C. Gwynne(917)

101 Things You Didn't Know About Lincoln by Brian Thornton(909)

Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen by Rae Katherine Eighmey(862)

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust(834)

Bloody Engagements by John R. Kelso(821)

Lincoln's Lieutenants by Stephen W. Sears(806)

Union by Colin Woodard(800)

Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman(797)

The escape and suicide of John Wilkes Booth : or, The first true account of Lincoln's assassination, containing a complete confession by Booth(766)

1861: The Civil War Awakening by Adam Goodheart(747)

Rise to Greatness by David Von Drehle(734)

The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery by Eric Foner(722)