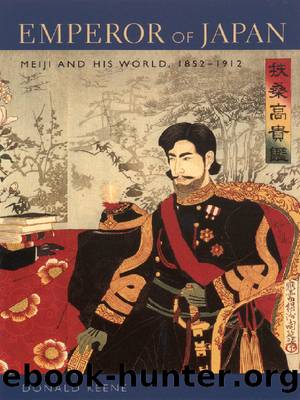

Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852â1912 by Keene Donald

Author:Keene, Donald

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History/Asia/General

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2011-01-30T16:00:00+00:00

Chapter 43

The remainder of 1891, once the excitement of the Åtsu incident had died down, was relatively tranquil. The most important political change occurred while the czarevitch Nicholas was still in KyÅ«shÅ«: Yamagata Aritomo announced his intention of resigning his post as prime minister. He had caught influenza during the epidemic in March, and although he had since recovered, he still did not feel himself. He recommended as his successor the president of the House of Peers, ItÅ Hirobumi. The emperor, having ascertained that it would not be possible to induce Yamagata to remain as prime minister, joined in the effort to persuade ItÅ to accept the post. ItÅ, who had submitted his resignation as president of the House of Peers, was traveling in the Kansai region when emissaries caught up with him and asked him to return to TÅkyÅ.

On April 27 ItÅ had an audience with the emperor during which the emperor stated his intention of appointing him as prime minister. ItÅ refused the appointment. He recalled that when Åkuma Shigenobu had proposed convening a parliament in 1881, he had opposed Åkuma, believing that preparations were incomplete and the Japanese people were not yet sufficiently mature. He had proposed delaying the opening of a parliament until he had investigated the constitutions and political institutions of various foreign countries and was later authorized to make such a journey. After his return, the constitution was promulgated, followed by the convening of the first Diet; but the intellectual level of the people remained low, and it was truly difficult to carry out constitutional government. ItÅ was sure that no matter who might become prime minister, he would not long remain in office. If he himself was obliged to serve in that position, he might well be assassinated. He would have no special regrets about losing his unimportant life, but if he were killed, who would assist the imperial household and preserve the government?1

ItÅ suggested that either Interior Minister SaigÅ Tsugumichi or Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi (1835â1924) would be suitable. On being informed of SaigÅâs unwillingness to accept the post, the emperor then chose Matsukata, who at first declined. The emperor refused to listen to his disclaimers, and Matsukata was sworn in as prime minister on May 6. The six months or so that he served in this capacity were marked by constant bickering in the Diet, leading in December to its dissolution and an election in the following year.

In July, Commodore Ting Ju-châang, in command of the Chinese Northern Seas Fleet, had an audience with the emperor. The audience was marked by the customary exchange of âorientalâ courtesies, but the six warships of the Chinese fleet (more powerful than any in the Japanese navy) inspired fear among some Japanese.

The visit of the Chinese fleet served as an occasion for those Japanese who had received a traditional education to demonstrate how much they knew about Chinese culture. Some referred deferentially to the Chinese as their âelder brothers.â2 Commodore Ting and the other high-ranking

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Story of China by Michael Wood(961)

Mr. Selden's Map of China by Timothy Brook(811)

Philippines--Culture Smart! by Culture Smart!(712)

Heroic Hindu Resistance To Muslim Invaders (636 AD to 1206 AD) by Sita Ram Goel(693)

Akbar: The Great Mughal by Ira Mukhoty(673)

First Platoon by Annie Jacobsen(664)

Vedic Physics: Scientific Origin of Hinduism by Raja Ram Mohan Roy(663)

The Meaning of India by Raja Rao(662)

Food of India by unknow(661)

Banaras by Diana L. Eck(653)

India--Culture Smart! by Becky Stephen(629)

China Unbound by Joanna Chiu(628)

North of South by Shiva Naipaul(626)

Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962 by Frank Dikötter(619)

Insurgency and Counterinsurgency by Jeremy Black(597)

The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention by Robert Temple(594)

A History of Japan by R.H.P. Mason & J.G. Caiger(588)

How to Be a Modern Samurai by Antony Cummins(587)

The Digital Silk Road by Jonathan E. Hillman(581)