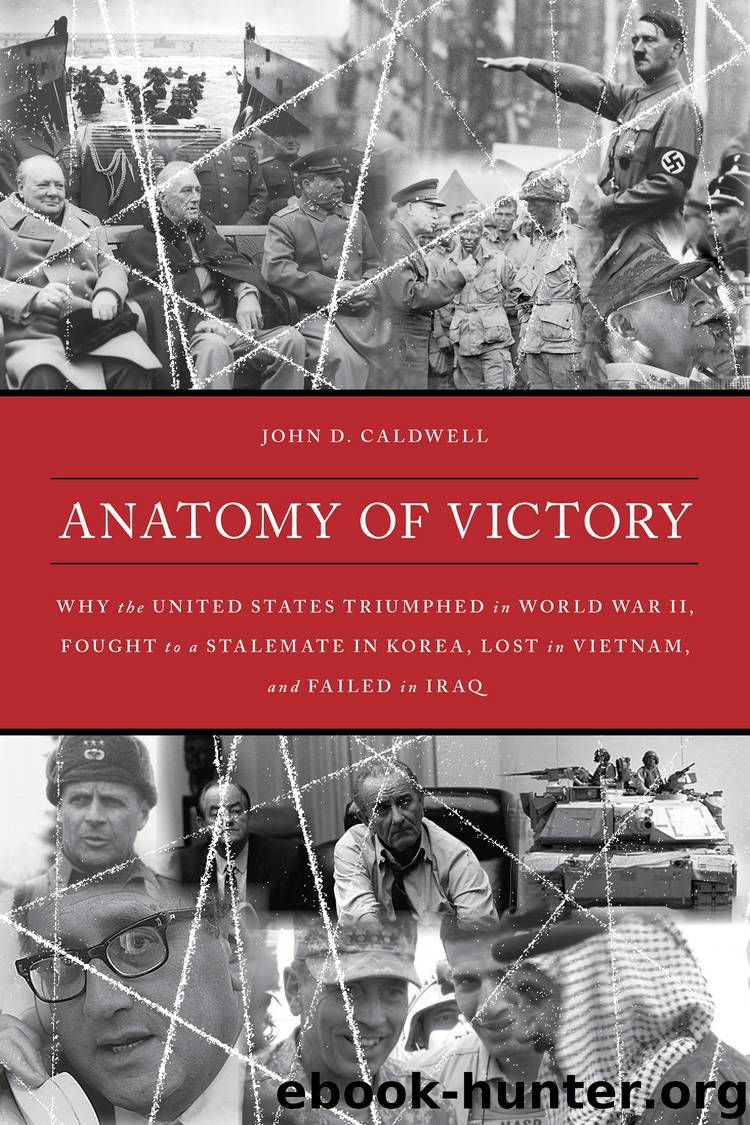

Anatomy of Victory: Why the United States Triumphed in World War II, Fought to a Stalemate in Korea, Lost in Vietnam, and Failed in Iraq by John D. Caldwell

Author:John D. Caldwell [Caldwell, John D.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield

Published: 2018-09-03T16:00:00+00:00

* * *

*Military Region was now the designation for a Corps Tactical Zone (Corps or CTZ).

23

The Strategic Architectures of the Vietnam War

After World War II and the Korean War, the Vietnam War represented a new kind of warfare. In the traditional sense, it was impossible to classify it simply as a war of combatant states and armies engaged in conventional battles. It was hardly a war in this old-fashioned sense of what American or European soldiers regarded war to be. One could not find or define a front until the last weeks of the war.

Vietnam presented for the first time a different set of problems for an American army that had a long history of operational learning. How does an army find, fix, and finish an enemy that it cannot find and engage at times and on terrain to its own strategic advantage, not the enemy’s? And how does it operate in the middle of a war surrounded by people whose language it cannot speak? Neither firepower nor technology was a war-winning discriminator if the target was so difficult to find. Success in the combat environment of Vietnam meant finding leaders who were capable of adapting and learning. It meant, in the best case, understanding the difference between Race’s preemptive and reinforcement policies, how they might affect Vietnamese behavior and motivation, and what policies created contingent incentives that could motivate military behavior to resist the NLF and Viet Cong.

Another difference was how this new kind of war was supported. In conventional conflicts, combatants are generally supplied from outside the locus of conflict. In a revolutionary conflict, the movement gets much of what it needs from the people it is trying to draw to its cause and seizes matériel and usable assets from the government it is trying to overthrow. That was one of the insights gained from the Malayan Emergency—isolate the insurgents from their source of supply. Malaya is a peninsula of some fifty thousand square miles with a narrow land border with Thailand1 and much of its territory, like Vietnam, uncultivated jungle. The insurgents could not benefit from an outside, geographically contiguous power to supply them. However, Vietnam offered no such advantage to COIN operators because geography worked against them. Vietnam had a porous, 1,200-mile border contiguous with North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, all countries providing routes for men and matériel to reinforce the revolutionary movement in South Vietnam. The Ho Chi Minh Trail proved impossible to interdict from the air, and serious proposals to block it with ground forces were rejected.

North Vietnamese Strategic Architecture

If the Vietnam War was not a traditional war fought by conventional combatants, there was general agreement among American and Vietnamese military leaders that the NVA and the NLF/VC cadres in the south were trying to impose their will on the South Vietnamese population through a unique strategy that blended military, political, and psychological elements of coercion and persuasion.

The revolutionary movement’s theory of victory was a simple one: Overthrow South Vietnam as

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

1-Bound by Honor(799)

The Saigon Sisters by Patricia D. Norland(706)

A Piece of My Heart by Keith Walker(588)

What We Inherit by Jessica Pearce Rotondi(583)

Where the Domino Fell by James S. Olson & Randy Roberts(566)

12, 20 & 5 by John Parrish(566)

The March of Folly by Barbara W. Tuchman(565)

Gunship Pilot by Robert F. Hartley(564)

Into Cambodia by Keith Nolan(563)

The United States, Southeast Asia, and Historical Memory by Pavlick Mark;(560)

We Were Soldiers Once...and Young by Harold G. Moore;Joseph L. Galloway(556)

Abandoning Vietnam by James H. Willbanks(553)

They Were Soldiers by Joseph L. Galloway(549)

Charlie Company's Journey Home by Andrew Wiest(539)

A Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941-1975 by Robert D. Schulzinger(522)

Carrier: A Guided Tour of an Aircraft Carrier by Tom Clancy(521)

Green Beret in Vietnam by Gordon Rottman(516)

Rethinking Camelot: Jfk, the Vietnam War, and U.S. Political Culture by Noam Chomsky(510)

Inside the Crosshairs by Col. Michael Lee Lanning(474)