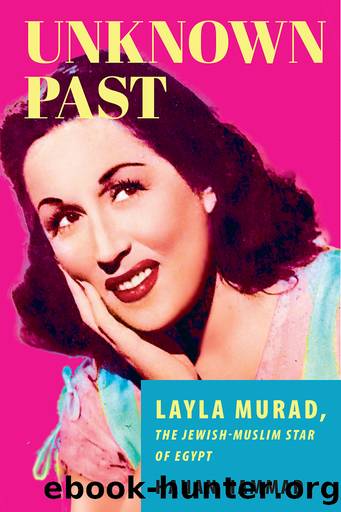

Unknown Past by Hanan Hammad;

Author:Hanan Hammad;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2022-06-15T00:00:00+00:00

By the end of 1952, the entertainment industry in Cairo wore patriotic and military uniforms, and performers enlisted themselves in backing the new military elite. Actresses appeared on the covers of celebrity magazines wrapped in the Egyptian flag and chanted the slogan of the new revolutionary regime: âal-Ithad wa al-Nizam wa al-âAmalâ (Unity, discipline, and work).33 Armed Forces sponsored concerts attended by the countryâs new leaders, including President Muhammad Nagib, Gamal âAbd al-Nasser, and the rest of the RCC (Revolutionary Command Council). These concerts attracted large audiences who celebrated the success of and backed the Free Officersâ Blessed Movement: on January 26, 1953, for example, 3,500 people attended a concert in al-Tahrir Theater in downtown Cairo.34

Layla Murad became the voice of the new regime in terms of celebrating and performing patriotism. In response to the Free Officersâ endorsement, she visited General Muhammad Nagibâs office before the end of the year and handed his secretary, Officer Magdi Hasanayn, a check for 1,000 pounds as a donation to the Egyptian army; the military leaders welcomed the donation and praised Layla as a role model of patriotism among artists.35 She called President Muhammad Nagib âmy fatherâ and publicized a photo of her holding a framed picture of Nagib and looking at it with admiration. She became the âofficialâ singing voice of the Free Officers when she performed the liberation anthem (âNashid al-Tahrirâ) widely known as ââAla Allah al-Qawiy al-Iâtimadâ (Upon almighty God we depend). The former head of Egyptian radio, Midhat âAsim, had composed the anthemâs melody and lyrics to greet Nagib and the Free Officers during the launch of Mustafa Kamil (Ahmad Badrkhan, 1952), a biopic about the Egyptian nationalist leader Mustafa Kamil (1874â1908)36 that had been banned by the authorities during the monarchy because it strongly denounced the British occupation and was released by the Free Officers once they came to power. To promote its highly patriotic content, Nagib had intended to attend the debut of the film in December 1952, but Officer Anwar Sadat, a member of the RCC, represented him instead. âAsim made clear the intensive engagement of the new regime, represented by Officer Wagih Abaza, in formulating the nashid. Abaza visited âAsim at his home to discuss the program for the film launch and to review his work-in-progress. âAsim readily accepted Abazaâs suggestion to use the musical format of the military march for the anthem âto attract attention and activate senses to listen.â37 He also adopted Abazaâs other suggestion, to add sentences about Sudan to the anthem. More important, Abaza supported Layla Muradâs request to perform the anthem, which âAsim welcomed enthusiastically.38 âAsimâs account proves that making Layla the voice of the new regime as a result of her close association with Abaza was intentional.

Studio Misr used the anthem in a short film along with Muhammad âAbd al-Wahabâs âNashid al-Wadiâ âto energize the high values of the liberation movement.â39 The radio broadcast Laylaâs âNashid al-Tahrirâ anthem extensively upon its recording in December 1952. Published radio program schedules from

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Phoenicians among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean by Denise Demetriou(595)

american english file 1 student book 3rd edition by Unknown(586)

Verus Israel: Study of the Relations Between Christians and Jews in the Roman Empire, AD 135-425 by Marcel Simon(584)

Caesar Rules: The Emperor in the Changing Roman World (c. 50 BC â AD 565) by Olivier Hekster(568)

Basic japanese A grammar and workbook by Unknown(552)

Europe, Strategy and Armed Forces by Sven Biscop Jo Coelmont(511)

Give Me Liberty, Seventh Edition by Foner Eric & DuVal Kathleen & McGirr Lisa(491)

Banned in the U.S.A. : A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries by Herbert N. Foerstel(479)

The Roman World 44 BC-AD 180 by Martin Goodman(469)

Reading Colonial Japan by Mason Michele;Lee Helen;(462)

DS001-THE MAN OF BRONZE by J.R.A(456)

The Dangerous Life and Ideas of Diogenes the Cynic by Jean-Manuel Roubineau(449)

Introducing Christian Ethics by Samuel Wells and Ben Quash with Rebekah Eklund(446)

Imperial Rome AD 193 - 284 by Ando Clifford(444)

The Oxford History of World War II by Richard Overy(444)

Catiline by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(412)

Literary Mathematics by Michael Gavin;(406)

Language Hacking Mandarin by Benny Lewis & Dr. Licheng Gu(399)

Brand by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(376)