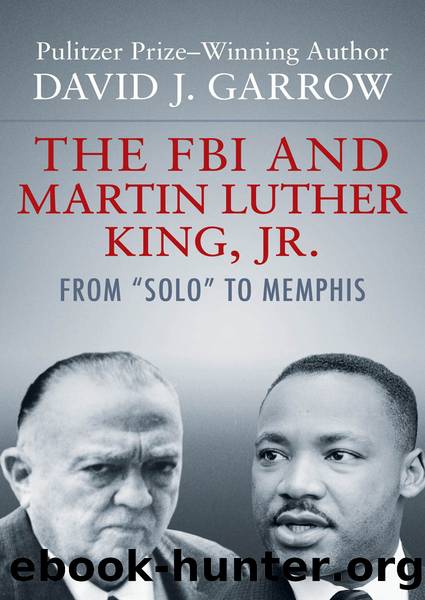

The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. by David J. Garrow

Author:David J. Garrow

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781504011532

Publisher: Open Road Media

6

The Radical Challenge of Martin King

The first two phases of the King investigation have been explained by the FBIâs preoccupation first with Stanley Levisonâs past and then with Martin Kingâs personal life. The third and last phase of the King probe was marked by an emphasis upon information about Kingâs political plans. That focus did not emerge until the late summer or fall of 1965.

Some who support this âpolitical-intelligenceâ thesis contend that the true purpose of the FBIâs pursuit of King and SCLC had always been to gather information on political strategy and demonstration plans, information that domestic security police obviously would want to obtain. Any ostensible FBI concern with âsubversivesâ or with Kingâs personal life, this argument says, was either a âcoverâ for or a concommitant of this larger political purpose. Proponents of this view have based their argument more on this presumption about the natural function of domestic security police than upon specific evidence.

Like the âconservatismâ argument, the political-intelligence thesis is true, but only in part. As early as the 1962 wiretapping of Stanley Levison, the Bureau was using what it overheard to report Kingâs and SCLCâs political plans to the Attorney General and other officials. In May, 1963, the substance of King-Levison conversations about Birmingham was furnished to the Attorney General and apparently the President. Even in 1964, at the height of the obsession with Kingâs private life, Bureau documents still spoke of how the wiretaps on Kingâs home and office were supplying important âintelligence on the racial movement.â Furthermore, what could be a clearer example of the use of FBI surveillance for political-intelligence purposes than the activities of DeLoachâs âspecial squadâ at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, and the hourly reports that were furnished to the White House?1

All of this, of course, can be cited to support the claim that the Bureau principally used the surveillance of King to gather political information useful to a government worried about racial protests and mass demonstrations.2 The problem, however, is that indications of such a focus before mid or late 1965 are the exception, rather than the rule, in FBI files on King and SCLC. Nothing presents this contrast more sharply than the Atlantic City events. The communications concerning that operation reflect a clear awareness of the strictly political purpose of the undertaking. Those indications are not mirrored in documents dealing with the Bureauâs other electronic activities directed against King and his associates, and it is important to remember that the Atlantic City squad was created not at the Bureauâs own initiative, but at the specific behest of Lyndon Johnson. As of the fall of 1964, the FBI had only an incidental interest in using its surveillances of King to gather purely political information for the governmentâs own use.

Why did a greater interest in political intelligence not emerge sooner? First, through late 1963 there was an overpowering focus on the activities of Stanley Levison, and indications of a broader orientation to the King case were rare. Indeed, most of

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spellbound by Christopher Pike(226)

Werewolves Don't Go to Summer Camp by Debbie Dadey(215)

Medusa and Pegasus by Amy Hayes(200)

Skulduggery Pleasant - the Complete Series Books 1-9 by Landy Derek(189)

GHOSTBUSTERS II (Yearling) by B.B. Hiller(181)

Meddling Mooli and the BlueLegged Alien by Asha Nehemiah(178)

The Berenstain Bears' Perfect Fishing Spot by Stan Berenstain(176)

365 Tales From Indian Mythology by Om Books Editorial Team(167)

Princesses Save the World by Savannah Guthrie; Allison Oppenheim(167)

Winter by Steven Schnur(167)

WANDA WEIRD by Rebecca Winch(165)

See Inside a Castle by R. J. Unstead(162)

I Want My Mum! by Tony Ross(159)

117 Days by Ruth First(156)

The Teen Witches' Guide to Spells by Xanna Eve Chown(154)

Disney Zombies: Welcome to Seabrook by Bonnie Steele(152)

The Mystery of the Two-Toed Pigeon by Marc Brandel(146)

Ghostbusters II by B. B. Hiller(144)

The Quest of Quinton by Brandon Keilen(143)