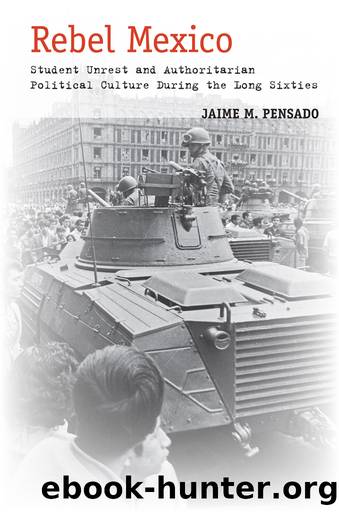

Rebel Mexico by Pensado Jaime M.;

Author:Pensado, Jaime M.; [Pensado, Jaime M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2013-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

7

âNo More Fun and Gamesâ: From Porristas to Porros

On December 1, 1958, Adolfo López Mateos replaced Ruiz Cortinez as the new president of Mexico. Universally revered by the Mexican and U.S. press, López Mateos was described as a younger, more articulate, and attractive leader than his predecessor. Some in the New York Times spoke of him as a âsymbol of Mexicoâs rising middle class.â1 Others in the U.S. press simply described him as âan eminently practical manâ and anticipated that the new president would govern Mexico in a much more progressive fashion. They were convinced that, unlike the older and more conservative General Ruiz Cortinez, the new civilian president would never bring shame to Mexicoâs democracy with the brutal use of the granaderos or the federal troops against ordinary citizens. Some reporters even suggested that, âat last, the new Cárdenas had arrived.â2 In Mexico, journalists tempered their enthusiasm but nonetheless expressed the hope that López Mateos represented what the nation needed during the difficult times of the Cold War: a leader who was âboth humane and tough at the same time.â3 The optimism reported in the U.S. and the national press reflected the feeling of many people that López Mateos had performed well as secretary of Labor and Social Welfare during the administration of Ruiz Cortinez. In this capacity he had established a good relationship with the labor unions. With âconciliation and arbitration,â an American journalist reported, â[the secretary of labor had] settled nearly 30,000 labor managerial disputesâ prior to the massive uprisings of 1958. Similar results were thus to be expected regarding the ideological polarization that came to characterize Mexico in the wake of the Cuban Revolution.4

As reported to the U.S. Department of State by U.S. ambassador Thomas Mann, the new presidential administration initially found favor with the anticommunism of Miguel Alemánâs Mexican Civic Front of Revolutionary Affirmation (FCMAR) and the nationalist tones of Lázaro Cárdenasâs Movement of National Liberation (MLN).5 However, when rumors began to surface that members of the two fronts wanted to transform their organizations into opposing parties, the presidential office took a number of steps to thwart their plans. As a general measure, Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) officials stated publicly that the only acceptable solutions to Mexicoâs problems were those embodied by the Mexican Revolution as institutionalized in the party. Under pressure from all sides, the administration of López Mateos tried to demonstrate its leftist intentions, on the one hand, and, on the other, it hoped to convince anticommunist forces in and out of government that Mexico would not become a hotbed of communism. In the first instance, in response to growing pressure from the Left to address the significance of Mexicoâs own revolution, the president made a statement that the âcourse and ideologyâ of his revolutionary government were of the âextreme left within the Constitution.â6 These remarks did not go unnoticed by various people and institutions concerned with the spread of communism in Mexico following the outbreak of the Cuban Revolution. When asked to

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

american english file 1 student book 3rd edition by Unknown(618)

Phoenicians among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean by Denise Demetriou(616)

Verus Israel: Study of the Relations Between Christians and Jews in the Roman Empire, AD 135-425 by Marcel Simon(596)

Basic japanese A grammar and workbook by Unknown(587)

Caesar Rules: The Emperor in the Changing Roman World (c. 50 BC â AD 565) by Olivier Hekster(585)

Europe, Strategy and Armed Forces by Sven Biscop Jo Coelmont(526)

Give Me Liberty, Seventh Edition by Foner Eric & DuVal Kathleen & McGirr Lisa(503)

Banned in the U.S.A. : A Reference Guide to Book Censorship in Schools and Public Libraries by Herbert N. Foerstel(495)

The Roman World 44 BC-AD 180 by Martin Goodman(481)

DS001-THE MAN OF BRONZE by J.R.A(472)

Reading Colonial Japan by Mason Michele;Lee Helen;(472)

Introducing Christian Ethics by Samuel Wells and Ben Quash with Rebekah Eklund(470)

Imperial Rome AD 193 - 284 by Ando Clifford(460)

The Dangerous Life and Ideas of Diogenes the Cynic by Jean-Manuel Roubineau(459)

The Oxford History of World War II by Richard Overy(457)

Catiline by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(454)

Language Hacking Mandarin by Benny Lewis & Dr. Licheng Gu(416)

Literary Mathematics by Michael Gavin;(411)

Brand by Henrik Ibsen--Delphi Classics (Illustrated) by Henrik Ibsen(408)