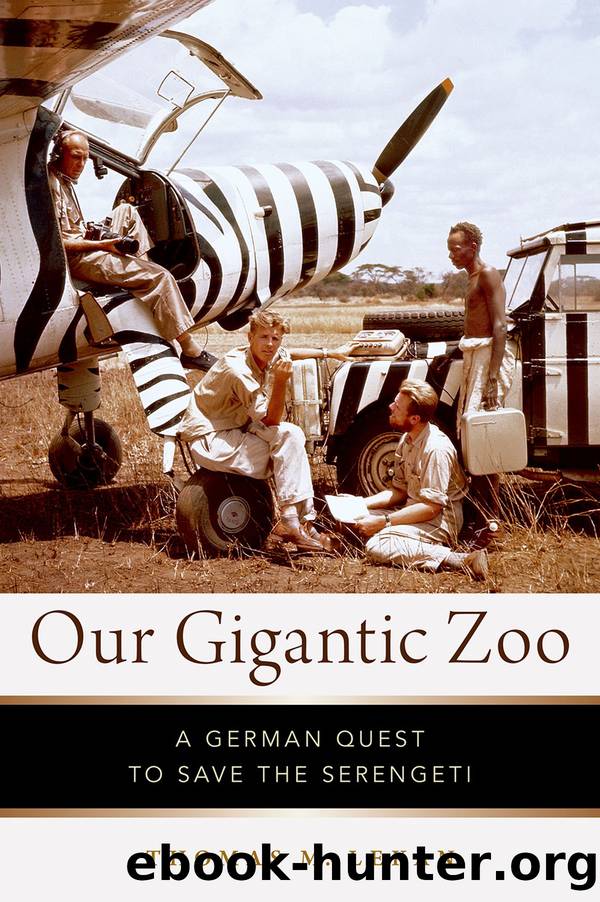

Our Gigantic Zoo by Thomas M. Lekan

Author:Thomas M. Lekan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2019-09-15T00:00:00+00:00

The reference to black and white men is key here, since the Grzimeksâ stage-theory of African development envisioned a postcolonial world in which industrious Africans, long held back by British policies, would move to cities, develop their landsâand lose all ties to wildlife. Without immediate intervention, children in both Berlin and Dar es Salaam would see wildlife only in zoos, not on the open range. Such operatic pleas ensured the Grzimeks a place at the table of the âworldâ conservation community that took on the task of administering the Serengeti as British imperial hegemony crumbled.

The vision of the Maasai âproblemâ as a product of overpopulation and a zero-sum battle between cattle and wildlife used the global threat of desertification to defuse intractable local and regional questions about appropriate land use and environmental sovereignty. Such overarching explanations blamed the Maasai for a series of historical missteps and ongoing environmental changes that had little to do with pastoralism, including a warming climate, previous European land alienations, dubious settlement schemes, and failed ranchland and cash-crop experiments.204 Numerous British observers noted that Maasai pastoralists saw beyond âmeats, skins, and competition for their hungered cowsâ but the Grzimeksâdoomsday vision of overpopulation and modernization subsumed complex interactions between pastoralists and wild animals into a global degradation narrative, reinforcing the belief that ânativeâ peoples had no place in a landscape designated by God to protect the animals.205

Despite their advanced gadgetry, Bernhard found his and Michaelâs work scrutinized continually for animal counts that were far too low and maps of the great migration routes that were far too prescriptive. The Grzimeksâ faith in aerial technology overlooked well-known sources of error, many scientists claimed, leaving census data and theories about migrations and grass species open to contestation and refinement for decades to come. Yet their work was not a purposeful misrepresentation, as some have argued, but part of an array of European wildlife management that had continually tried, and failed, to render the plains legible and manageable.206 Determining the exact numbers and migration routes of East African animals had long bedeviled colonial officials, and the Grzimeks made these counts more precise and connected the dots between animal movements, rainfall, and vegetation. Yet they shared a late colonial European assumption that saw tropical savannas as especially vulnerable to overgrazing and soil erosion, which led all involvedâfrom Hingston through the Grzimeksâto target pastoralists, not poachers, as the greatest long-term threat to the Serengeti as an ecosystem. European observers consistently underestimated the ability of the plains to bounce back from drought and overestimated the capacity of rural pastoralists to inflict permanent damage.207

The unruly, âdisturbance-mediatedâ qualities of the Serengetiâs ecosystems that made causal explanations so daunting were quite evident to those closer to the ground: the district officers, game scouts, and rural Africans who wrestled with shifting conditions that never settled down into the equilibrium state predicted by the scientific wildlife managers. Nature surfaces in colonial reports as capricious and unwieldy, stymying efforts to protect wandering animal herds, police the borders of the park, and manage its amenities for tourists.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Migrants and Strangers in an African City by Bruce Whitehouse(155)

Archives of the Empire by Vol II(123)

Four Months Besieged by Henry H. S. Pearse(114)

Mennonites and Post-Colonial African Studies by John M. Janzen Harold F. Miller John C. Yoder(109)

The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, From 1865 to His Death, Volume I (Of 2), 1866-1868 by David Livingstone(106)

More Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey by Amy Jacques Garvey(102)

South Africa and the Transvaal War, Vol. 4 (of 8) by Louis Creswicke(102)

South Africa and the Transvaal War, Vol. 6 (of 8) by Louis Creswicke(102)

Ismailia by Baker Samuel White Sir(95)

Outsourcing African Labor by Jeffrey Gunn(94)

A History of the AbaThembu People from Earliest Times To 1920 by Jongikhaya Mvenene(94)

The Upper Guinea Coast in Global Perspective by Jacqueline Knörr Christoph Kohl(93)

State and Culture in Postcolonial Africa by TEJUMOLA OLANIYAN(91)

An Account of Timbuctoo and Housa Territories in the Interior of Africa by Shabeeny Abd Salam active 1820(89)

Travel and the Pan African Imagination by Tracy Keith Flemming(86)

Our Gigantic Zoo by Thomas M. Lekan(74)

Struggles for Self-Determination: The Denial of Reactionary Statehood in Africa by Josiah Brownell(71)

The Record of a Regiment of the Line by Mainwaring George Jacson(65)

Landlords And Strangers: Ecology, Society, And Trade In Western Africa, 1000-1630 by George E. Brooks(51)