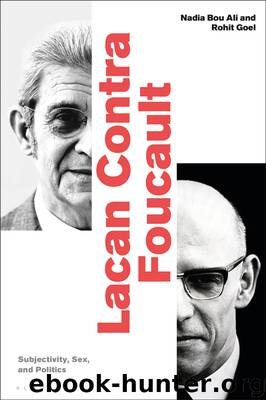

Lacan Contra Foucault by Nadia Bou Ali Rohit Goel

Author:Nadia Bou Ali,Rohit Goel

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury UK

5

Battle Fatigue: Kiarostami and Capitalism

Joan Copjec

Taste of Cherry, winner of the 1997 Cannes film prize, is the bleakest film in Abbas Kiarostami’s oeuvre. By 1988, Iran’s devastating eight-year war with Iraq, which erupted on the heels of the bloody 1978/79 revolution, had finally ended, but battle fatigue and disillusionment are still palpable throughout the film. Explicit references to these conflicts and the lingering presence of militia, together with the desperate conditions of day labourers, who hang around looking to pick up whatever work they can, serve as reminders that capitalism had been operating behind the scenes all along, manipulating and prolonging the conflicts for sheer financial gain. The lush vistas of the director’s other films are sadly absent, replaced here by a flinty, peri-urban landscape. Bulldozers emit harsh sounds as they claw the ground as if to rip out, root and branch, the lone tree on a hill that is a signature presence in many of Kiarostami’s films but nowhere visible here. That this is a world made up almost entirely of men is an indication not of the director’s indifference to the plight of women, as some feminists complained, but of the arid conditions that everywhere quash desire and foster despair.

Sometime before the film began, Mr. Badii apparently took the decision to commit suicide, for he spends most of his screen time trying to accomplish what turns out to be this not-so-simple task. The film focuses on his unusual strategy to carry out his resolve. Regarding Mr. Badii’s nihilistic decision, Kiarostami had this to say in an interview: ‘the choice of death is the only prerogative left to a human being with respect to God and social norms. Because everything in our life has been imposed on us from birth, our date and place of birth, our parents, our home, our nationality, our build, the color of our skin, our culture.’1 If Kiarostami felt compelled to offer an explanation, it is because the narrative does not. Badii, an urban, educated, middle-class man who minds his health and drives a Land Rover, seems to have been favoured by God and social norms, unlike the out-of-work labourers from Iran’s ethnic underclass, who struggle to eke out a living. There is no hint of anything lacking in his life, of any particular circumstance that might produce the sense of unfreedom and despair evoked in the director’s explanation. This is not to retract the suggestion that Badii’s despondency is related to the grim political and economic conditions on view in every frame. It suggests, rather, that by making its protagonist more of a cipher, the film transforms the way we read the site of traumatic inscription. Rather than a psycho-social narrative about the debilitating effects on the psyche of this new form of poverty, Kiarostami gives us something else. In place of psychological depth, he focuses on psychic interiority.

In order to understand this transformation, I want to supplement Kiarostami’s explanation with a passage in which Emmanuel Levinas describes a situation very much like

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Act of Living by Frank Tallis(805)

Genius & Anxiety by Norman Lebrecht(802)

Ego and Archetype by Edward F. Edinger(744)

Man's Search For Meaning: The classic tribute to hope from the Holocaust by Viktor E Frankl(666)

A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis & Dream Psychology (Psychoanalysis for Beginners) by Sigmund Freud(659)

The Ethics of Psychoanalysis 1959-1960 by Lacan Jacques Miller Jacques-Alain(658)

[1930] Civilization and Its Discontents by Sigmund Freud(650)

Highsmith, Patricia - Ripley's Game by Highsmith Patricia(642)

Genius and Anxiety by Norman Lebrecht(636)

[1905] Jokes And Their Relation To The Unconscious by Freud Sigmund(613)

Power of Gentleness: Meditations on the Risk of Living by Anne Dufourmantelle(566)

The Neurotic Personality Of Our Time (International Library of Psychology) by KAREN HORNEY(540)

Freud- The Key Ideas by Ruth Snowden(534)

Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. (From Vol. 8. of the Collected Works of C. G. Jung) (Jung Extracts) by Jung C. G(488)

Acquiring Genomes by Lynn Margulis(465)

Self and Emotional Life by Adrian Johnston & Catherine Malabou(460)

Labyrinths(443)

Psychoanalysis by Janet Malcolm(436)

Four Lessons of Psychoanalysis by Moustafa Safouan(423)