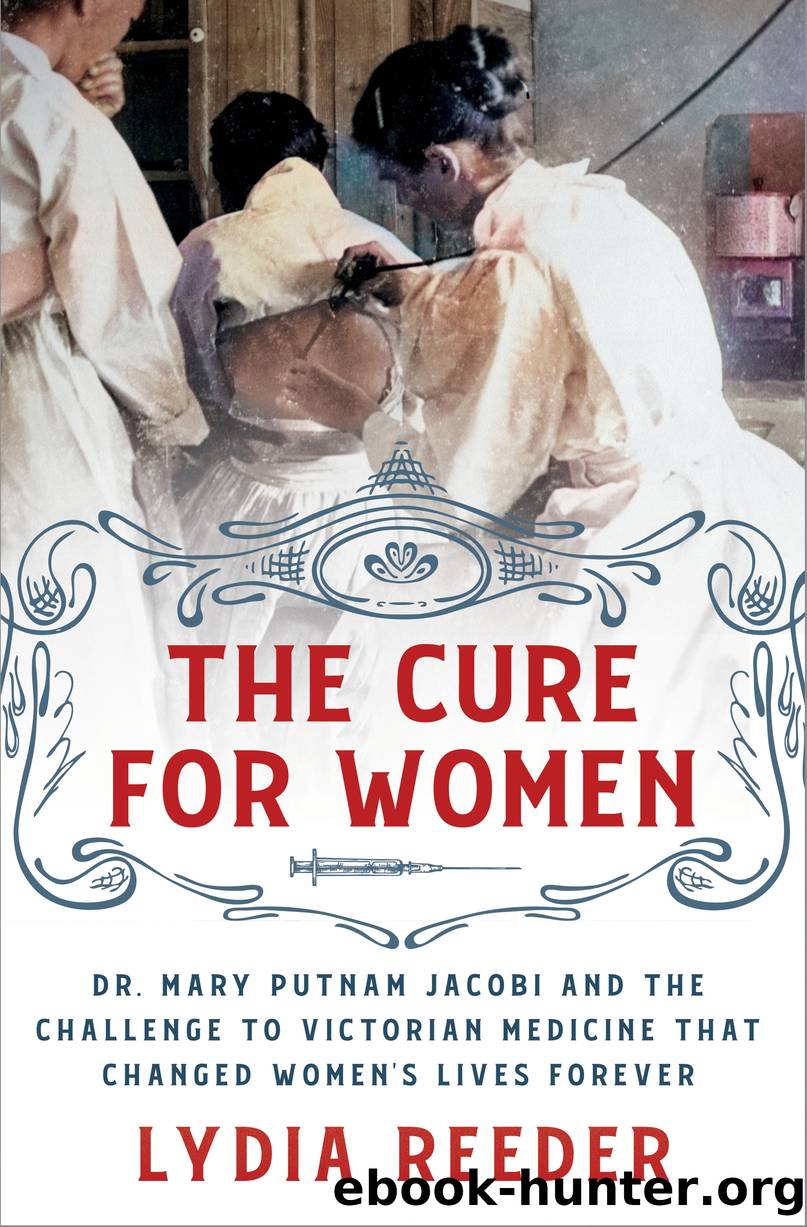

The Cure for Women by Lydia Reeder

Author:Lydia Reeder

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

* * *

Jacobi then analyzed the results of her questionnaire. Of the thousand distributed by Baker and others, 268 were returned, an acceptable number. They came from a varied cross-section of American women. Performing extensive statistical calculations using simple averages, Jacobi evaluated the relationships among her questions, divided respondents into categories, and standardized their responses. Then she took these self-reports from women and inserted them into her report, thus adding, for the first time, womenâs stories to the medical record.

In one table, Jacobi correlated the respondentsâ general health with the number of miles that they walked daily. Answers to the question about general health included âVery fine,â âMens. this morning. Some pain of steady character,â âGood. Sick headache,â and âGood until child bearing.â They reported miles walked daily as âLong dist.,â â2â3,â âFour miles till after 2nd child,â âAll day,â and â20 miles.â

Next, she reported facts about menstruation and menstrual pain. While 65 percent of respondents suffered varying degrees of menstrual pain, from almost nothing to fairly severe, a full 35 percent reported suffering no pain at all. She correlated these answers with amount of exercise, family history, education, and occupation. Jacobi found that immunity from menstrual suffering did not depend on rest but on a healthy childhood, proper exercise, a sound education, marriage at a âsuitableâ time (when she was old enough to make her own decisions), and a steady occupation.

Overall, the survey portrayed American women as active, healthy, and industrious; women with âexcellentâ health who walked five to twenty miles a day were not likely to be incapacitated by menstruation. They were the opposite of fragile. She used their voices to counteract Clarkeâs paternal and condescending style of reporting so-called true stories about his unstable, sickly, and feminine patients. Jacobiâs firsthand reports were more authoritative than Clarkeâs personal stories about his handful of patients could ever be.

She concluded this section by stating, âRest during menstruation cannot be shown, from our present statistics, to exert any influence in preventing pain, since, when no pain existed, [rest] was rarely taken.â She noted one exception: working-class women, those who labored in the fields or factories and were on their feet for hours. Depending on the job conditions, these women might require extra rest during menstruation, but for the most part, too much rest was injurious. In fact, because women experienced a buildup of nutritional reserves during menstruation, Jacobi argued that it was actually a time of âincreased vital energy,â not sickness.

To prove this assertion and demonstrate the wave theory of womenâs reproduction, Jacobi did further research on a small number of subjects at the New York Infirmary. In a section titled âExperimental,â she tracked their cycles, measured pulse rates, took their temperatures, and determined their strength.

She began the section by stating her premise: âOn the hypothesis that the menstrual period represents the climax in the development of a surplus of nutritive force and material, we should expect to find a rhythmic wave of nutrition gradually rising from a minimum point just after menstruation, to a maximum just before the next flow.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Psychiatry and Racial Liberalism in Harlem, 1936-1968 by Dennis A. Doyle(139)

The Cure for Women by Lydia Reeder(133)

The Stem Cell Hope by Alice Park(121)

Doctors of Deception : What They Don't Want You to Know About Shock Treatment by Linda Andre(120)

Doctoring Freedom by Gretchen Long(116)

9781836207139 by Miguel Gonzalez(115)

How Not to Study a Disease by Karl Herrup(112)

The Daly Dish Bold Food Made Good by Daly Gina;Daly Karol;(110)

Tissue Engineering: Principles and Practices by Fisher John P(108)

How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation by Mark Paterson(105)

A Secret Mind by Kaye Kelly(100)

Pharmaceutical Medicine and Translational Clinical Research by Vohora Divya;Singh Gursharan; & Gursharan Singh(96)

Summary and Analysis of Patient H.M. by Worth Books(94)

Proper People: Early Asylum Life in the Words of Those Who Were There by David Scrimgeour(93)

Mary Putnam Jacobi and the Politics of Medicine in Nineteenth-Century America by Carla Bittel(89)

The Right Carb by Nicola Graimes(85)

Medical Applications of Beta-Glucan by Gürünlü Betül;(85)

Women Doctors in War by Judith Bellafaire; Mercedes Herrera Graf(84)

Mixing Medicines by Griffin Clare;(82)