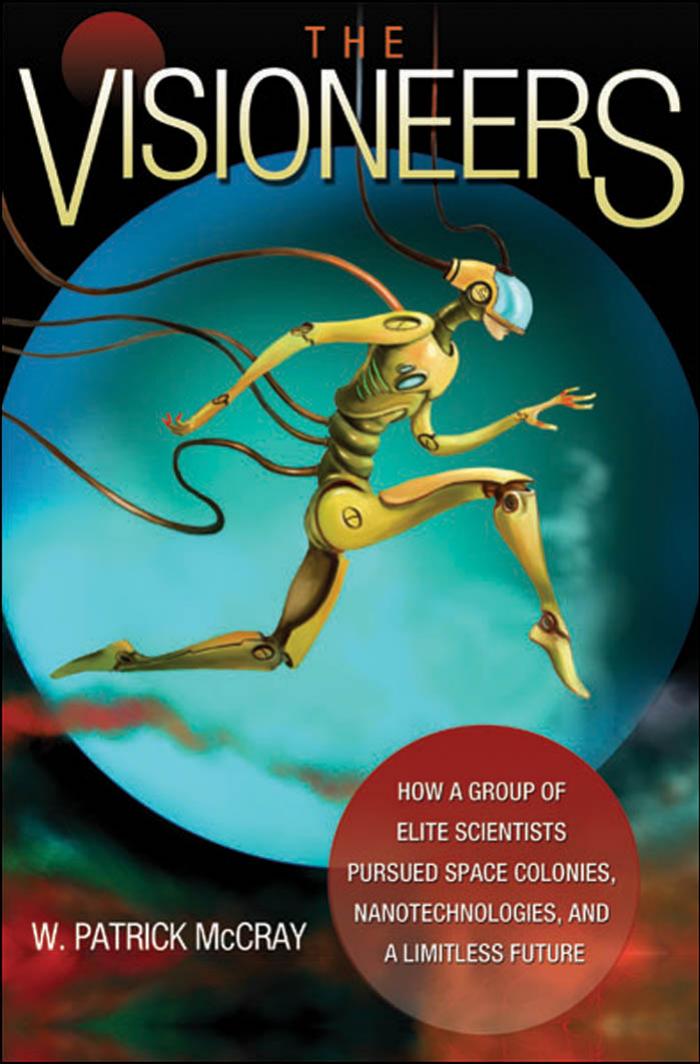

The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future by W. Patrick McCray

Author:W. Patrick McCray [McCray, W. Patrick]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9780691176291

Google: GQi-Pq7Rl3oC

Amazon: 0691176299

Published: 2012-12-09T13:59:42+00:00

CHAPTER 6

California Dreaming

As Iâve said many times, the future is here. Itâs just not very evenly distributed.

âWilliam Gibson, science fiction author, interview on National Public Radio, November 30, 1999

Only a few years after nanotechnology had blossomed into a global research initiative that consumed billions of government and corporate dollars, one well-placed observer claimed the field, if indeed nanotechnology could be delimited to such a thing, was experiencing an âexistential crisis.â1 But how could the âbrave and wondrous new worldâ of nanotechnology already be in such a perilous state?2

One answer was that nanotechnology wasnât new. Quite the opposite. Despite the oft-used revolutionary rhetoric, its foundations were rooted in Cold Warâera microelectronics and molecular biology. Scientists like von Hippel and Feynman proposed a future in which precise manipulation of the molecular realm was attainable. Early nano visionaries like Conrad Schneiker and Eric Drexler built on these imaginative ideas, adding concepts drawn liberally from two decades of advances in biology, microelectronics, and computer engineering. Schneiker had even deliberately used the term âFeynman machineâ to âemphasize the fact that this field wasnât just something that came up, that these ideas werenât brand new.â3 Drexler, meanwhile, proceeded to popularize what he only gradually, and somewhat reluctantly, called nanotechnology.

The existential quandary also emerged because there was no single entity to which one could point and say âThat is nanotechnology.â Nanotechnology wasnât like Thomas Newcomenâs steam engine or Henry Fordâs assembly line. It was instead a broad and enabling set of technologies for production and a rubric of ideas that purported to contain the seeds for radical social and economic change. Seen this way, it more closely resembled the scientific management of Taylorism, the early-twentieth-century principles of âscientific managementâ that proposed how assembly lines and factories should be organized. Much closer to an ideology than to actual nuts-and-bolts engineering, Taylorism (and nanotechnology) helped unite a community of adherents and boosters in pursuit of a new future for industry and society.

Like Fordâs assembly lines, nanotechnology appeared during and drew on an extraordinary period of American technological and industrial change. Following the end of World War Two, a powerful new social contract emerged between universities, business, and government. The participants in this âtriple helixâ framed scientific research and technological development as essential components of Americaâs global power during the Cold War.4 Established disciplines like physics and chemistry grew handsomely while new fields like materials science, molecular biology, and computer science emerged and thrived. Although nanotechnology today has the cachet of cutting-edge science and engineering, its proponents foraged extensively on the many intellectual and technological frontiers that researchers had opened during this prolific period.

Even among its early supporters, nanotechnology possessed a certain plasticity. This flexibility allowed proponents such as Schneiker and Drexler to interpret and imagine it in diverse ways. Following Drexlerâs successful popularizing, ânanotechnologistsâ from a wide array of academic disciplinesâbiology, physics, chemistry, materials science, engineering, each with its own argot, professional societies, conferences, and journalsâembraced a broad ensemble of tools and techniques. Meanwhile, the visioneering of people like

Download

The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future by W. Patrick McCray.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(13052)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12029)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6336)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(6234)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(5785)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(5641)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4536)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(4507)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(4445)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3905)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(3826)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3800)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(3771)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3754)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(3701)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3631)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(3579)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3515)

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff & Amy Matthews(3394)