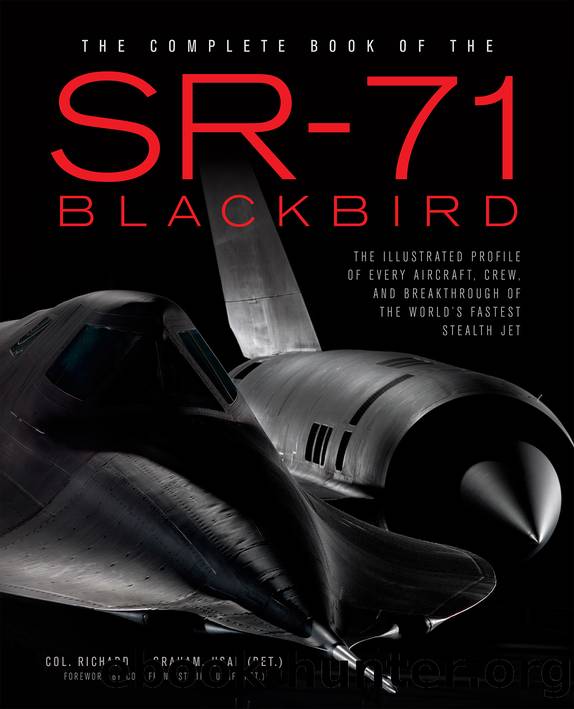

The Complete Book of The SR-71 Blackbird by Col. Richard H. Graham USAF (Ret.)

Author:Col. Richard H. Graham, USAF (Ret.)

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Zenith Press

Published: 2015-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

Intelligence Sensors

The primary imaging sensor for the SR-71 was located in the nose of the aircraft. The entire nose section housed a remove-and-replace sensor that contained either a radar imaging system or a photographic camera. The radar sensor was originally used as our fallback sensor in case the target weather was not suitable for photographic coverage. As the radar sensor became more sophisticated and produced greater resolution, it was no longer a fallback sensor.

Weather approval from SAC headquarters was required prior to each operational mission in order to launch with a photographic camera on board. Each photo sortie was required to have a certain percentage of cloud-free coverage (usually around 70 percent) in the target area before flying the mission. Crews liked radar missions better because they were not dependent on target weather and would always launch. There were many days the entire detachment went through the complete drill of preparing the aircraft, loading sensors, briefing the mission, getting the tankers airborne, and then canceling at the last minute because of poor target weather forecast by the SAC Headquarters Global Weather department. The total effort that went into preparing for each sortie was tremendous.

A classic example of this drill occurred in March 1979 when Don and I and pilot Buz Carpenter and RSO John Murphy were deployed on TDY (Temporary Duty) to RAF Mildenhall with the SR-71 to fly a specific reconnaissance mission into Yemen. Tensions were building between Yemen and Saudi Arabia, and the US government wanted more intelligence on these events. All four of us did a weather drill for four consecutive days until the clouds finally cleared in the target area to launch. Every morning we went through the same routine—2:00 a.m. wake up for a 5:00 a.m. takeoff—only to end up with the crew in the cockpit ready to go and the mission canceled. Every night we had to be in crew rest by 6:00 p.m., which left little time for socializing. Consequently, after each cancellation we drove back to our bachelors officers quarters (BOQ) to start our 6:00 a.m. party. Our friendly British “senior citizen” BOQ maids, Elsie, Janet, and Phyllis, arrived for work around 8:00 a.m. only to find the four of us listening to music and enjoying life with a glass of booze. Vodka tonic was my drink of choice They thought we had partied all night long for four days in a row! Little did they know.

Our two primary sensors were either the high-resolution optical bar camera (OBC), used for taking panoramic photography, or the side-looking radar system known as capability reconnaissance (CAPRE, pronounced “caper”). Both sensors were carried in the nose of the aircraft. The OBC camera used a continuously moving roll of film. In operation, the camera took photographs while scanning from left to right across the SR-71’s flight path. The OBC’s terrain coverage was 2 nautical miles along the ground track and extended 36 nautical miles to each side of the aircraft (further if banked). Sufficient film was onboard to cover approximately 2,952 nautical miles, or 1,476 nautical miles in the stereo mode.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Shoot Sexy by Ryan Armbrust(17142)

Portrait Mastery in Black & White: Learn the Signature Style of a Legendary Photographer by Tim Kelly(16484)

Adobe Camera Raw For Digital Photographers Only by Rob Sheppard(16387)

Photographically Speaking: A Deeper Look at Creating Stronger Images (Eva Spring's Library) by David duChemin(16161)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13108)

Art Nude Photography Explained: How to Photograph and Understand Great Art Nude Images by Simon Walden(12348)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(4621)

Pillow Thoughts by Courtney Peppernell(3397)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3217)

Good by S. Walden(2915)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2739)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(2543)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(2518)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2379)

Read This If You Want to Take Great Photographs by Carroll Henry(2303)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2270)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2130)

Photographic Guide to the Birds of Indonesia by Strange Morten;(2088)

Insomniac City by Bill Hayes(2083)